The first practicable method of colour photography was the autochrome process, invented in France by Auguste and Louis Lumière. Best known for their invention of the Cinématographe in 1895, the Lumières began commercial manufacture of autochrome plates in the early 20th century.

The autochrome in a nutshell

Who invented the autochrome?

The autochrome process, also known as the Autochrome Lumière, was invented in France by brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière.

The Lumière brothers presented their research into colour photography to the Académie des Sciences in 1904. The commercial manufacture of autochrome plates began in 1907, and the first public demonstration of the autochrome process took place on 10 June 1907, at the offices of the French newspaper L‘Illustration.

How do autochromes work?

Autochrome plates are covered in microscopic red, green and blue coloured potato starch grains (about four million per square inch). When the photograph is taken, light passes through these colour filters to the photographic emulsion. The plate is processed to produce a positive transparency. Light, passing through the coloured starch grains, combines to recreate a full colour image of the original subject.

How were autochromes made?

The manufacture of autochrome plates was undertaken at the Lumière factory in Lyon, and was a complex industrial process. First, transparent starch grains were passed through a series of sieves to isolate grains between ten and fifteen microns (thousandths of a millimetre) in diameter. These microscopic starch grains were separated into batches, dyed red, green and violet, mixed together and then spread over a glass plate coated with a sticky varnish.

Next, carbon black (charcoal powder) was spread over the plate to fill in any gaps between the coloured starch grains. A roller submitted the plate to a pressure of five tons per square centimetre in order to spread the grains and flatten them out. Finally, the plate was coated with a panchromatic photographic emulsion.

How were autochromes taken?

They did not require any special apparatus—photographers could use their existing cameras. However, they did have to remember to place the autochrome plate in the camera with the plain glass side nearest the lens so that light passed through the filter screen before reaching the sensitive emulsion.

Exposures were made through a yellow filter which corrected the excessive blue sensitivity of the emulsion for a more accurate colour rendering. This, combined with the light-filtering effect of the dyed starch grains, meant that exposure times were very long, about thirty times that of monochrome plates.

How were autochromes viewed?

For private viewing, autochromes could simply be held up to the light. However, for ease and comfort, they were usually viewed using special stands, called diascopes, which incorporated a mirror. These gave a brighter image and allowed several people to look at the plate at the same time. For public exhibition, autochromes were also projected using a magic lantern.

The story of the autochrome

In search of colour

In 1839, when photographs were seen for the first time, they were regarded with a sense of wonder. However, this amazement was soon tempered by disappointment: photographs captured the forms of nature with exquisite detail, yet failed to record its colours. The search for a practical process of colour photography soon became photography’s ‘Holy Grail’.

Attempting to meet consumer demand, photographers began to add colour to monochrome images by hand. Even at its very best, however, hand-colouring remained an arbitrary and ultimately unsatisfactory solution.

In 1861, James Clerk Maxwell conducted an experiment to prove that all colours can be reproduced through mixing red, green and blue light. This principle was known as additive colour synthesis. With the fundamental theory in place, several pioneers did succeed in making colour photographs, but their processes were complex, impractical and not commercially viable.

It was not until the end of the 19th century that the first so-called ‘panchromatic’ plates, sensitive to all colours, were produced. Now, at last, the way lay clear for the invention of the first practicable method of colour photography: the autochrome process, invented in France by Auguste and Louis Lumière.

Inventing the autochrome

The Lumière brothers are best known as film pioneers: they invented the Cinématographe in 1895. However, they had also been experimenting with colour photography for several years. In 1904, they presented the results of their work to the French Académie des Sciences. Three years later they had perfected their process and had begun the commercial manufacture of autochrome plates.

On 10 June 1907, the first public demonstration of their process took place at the offices of the French newspaper L‘Illustration. The event was a triumph. News of the discovery spread quickly and critical response was rapturous. Upon seeing his first autochrome, for example, the eminent photographer Alfred Stieglitz could scarcely contain his enthusiasm:

The possibilities of the process seem to be unlimited and soon the world will be color-mad, and Lumière will be responsible.

Making and using autochromes

Although complicated to make, autochrome plates were comparatively simple to use—a fact that greatly enhanced their appeal to amateur photographers. Moreover, they did not require any special apparatus: photographers could use their existing cameras.

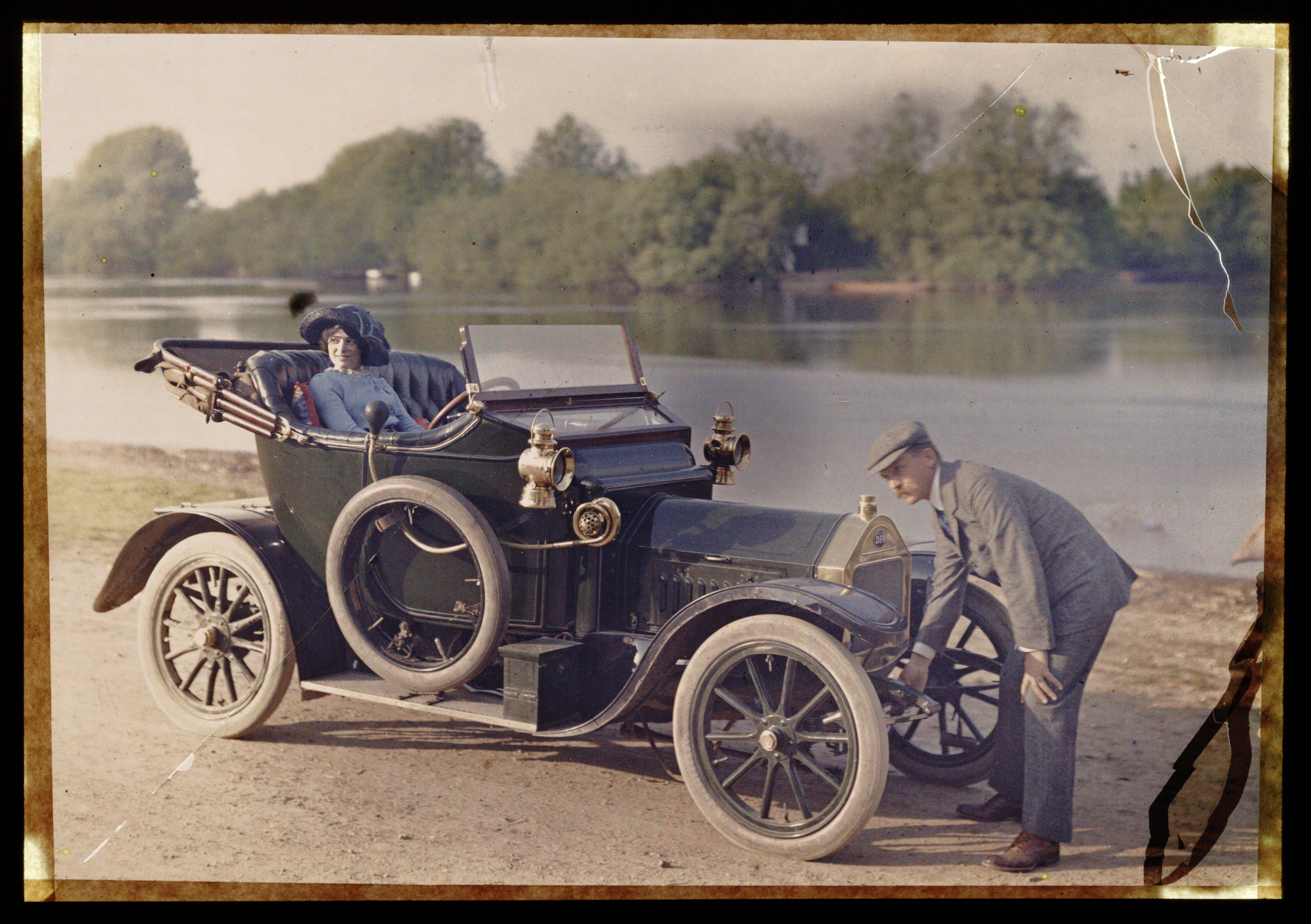

Exposures were made through a yellow filter which corrected the excessive blue sensitivity of the emulsion and gave a more accurate colour rendering. This, combined with the light-filtering effect of the dyed starch grains, meant that exposure times were very long—about thirty times that of monochrome plates. A summer landscape, for example, taken in the midday sun, still required at least a one-second exposure. In cloudy weather, this could be increased to as much as ten seconds or more. Spontaneous ‘snapshot’ photography was out of the question, and the use of a tripod was essential.

Following exposure, the plate underwent development to produce a positive transparency. In the finished plate, transmitted light, passing through the millions of tiny red, green and blue-violet transparent starch grains, combines to give a full colour image.

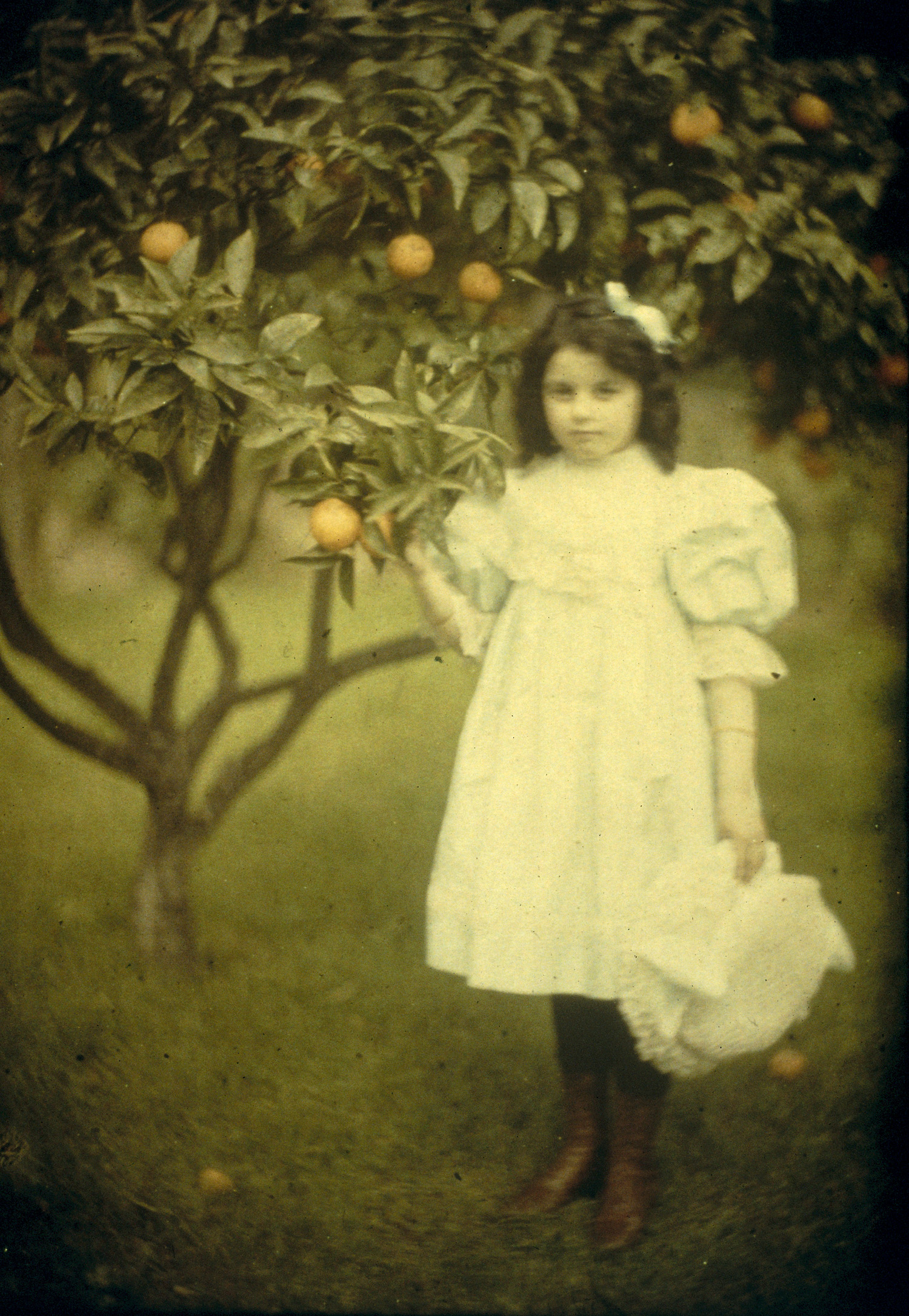

The beauty of the autochrome

No mere technical description, however, can adequately convey the inherent luminous beauty and dream-like quality of an autochrome, reminiscent of pointillist or impressionist painting. This beauty has a very down-to-earth explanation. In theory, the coloured starch grains were distributed randomly. In practice, however, some grouping of grains of the same colour is inevitable. While individual starch grains are invisible to the naked eye, these clumps are visible—the reason for the autochrome’s unique and

distinctive beauty.

Many photographers were bewitched by the twin spells of depth and colour. Stereoscopic autochromes, viewed in stereoscopes, were particularly effective, as The Photographic News noted in 1908:

…when the effect of relief is joined to a life-like presentation in colour the effect is quite startling in its reality. It is not easy to imagine what the effect of anything of this kind would have been on our ancestors and witchcraft would have been but a feeble, almost complimentary term, for anything so realistic and startling.

As the name itself suggests, the beauty of the autochrome depended largely on the process itself rather than in any personal intervention by the photographer, whose role was confined to composition rather than manipulation. Crucially, for the first time, photographers now had to develop an empathy with colour closer to that of painters. As the distinguished photographer Robert Demachy soon realised, ‘the Lumière process will make us learn the intricate laws of colour’.

Autochromes in high demand

Following highly favourable publicity in the summer of 1907, photographers were naturally keen to try out autochrome plates for themselves. At first, however, they were to be frustrated since demand far outstripped supply. It was not until October that the first, eagerly awaited, consignment of plates went on sale in Britain. By 1913, the Lumière factory was making 6,000 autochrome plates a day, in a range of different sizes.

In its annual survey for 1908, Photograms of the Year commented on the growing interest in the autochrome process. The Salon Exhibition of 1908, for example, contained almost 100 autochromes by leading figures such as Edward Steichen, Baron Adolf de Meyer, Alvin Langdon Coburn and James Craig Annan. These were the subject of considerable critical attention.

The problems with autochromes

The complexity of the manufacturing process meant that autochrome plates were inevitably more expensive than monochrome. To compensate for this, autochrome plates were sold in boxes of four, rather than the usual twelve. In 1910, a box of four quarter-plates cost three shillings (15p), compared with two shillings (10p) for a dozen monochrome plates. Their relatively high cost was the subject of frequent comment in the photographic press and clearly had some effect in limiting the process’s wider popularity.

After a brief period of intense interest, most ‘artistic’ photographers soon abandoned the process. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, autochromes were extremely difficult to exhibit. Secondly, the process did not allow for any manipulation of the final image. For many photographers, the autochrome, unlike printing processes such as gum and bromoil, was a totally unresponsive and therefore ultimately unsatisfactory medium, inherently unsuited to the ‘pictorialist’ aesthetic.

Robert Demachy commented that ‘we must resign ourselves to the inevitable atrocities that the over-confident amateur is going to thrust upon us’. Many prominent photographers, too, found themselves adrift in an alien world of colour—a world that they were very glad to leave behind as soon as the initial novelty and excitement had worn off.

Amateur photographers and the autochrome

The vast majority of autochromes were taken by amateur photographers, attracted to the process by the novelty of colour combined with its comparative simplicity.

In 1908, R Child Bayley, editor of Photography magazine, wrote an article on the process for The Strand magazine. Bayley was keen, above all, to stress its advantages for the amateur photographer:

There is now a process by which we can get a faithful picture in the camera, giving us the colours of Nature in a most startlingly truthful way. Moreover, it is essentially an amateur process. It calls for no great amount of skill and takes no great time to work.

Many amateur photographers eagerly embraced the world of colour that was now, finally, within their grasp. The subjects chosen by this first generation of colour photographers reflected both the possibilities of the autochrome process and its inherent technical limitations.

Popular subjects for autochrome photography

A colourful subject was paramount, and even if absent in nature, could always be introduced through props such as parasols. Portraiture was, of course, a very popular application. While indoor portraiture was possible, the long exposure times required meant that most portraits were taken outdoors. The sunny garden portrait with a background of a flower border or trellis quickly became a visual cliche of the autochrome process. Gardens themselves, with or without people, were also a popular subject. As The British Journal of Photography noted:

Colour is the very essence of the delight of the garden… The garden lover wants photographs as records of what he has accomplished, and which will last long after the glory of the original has departed.

Flowers were probably the most frequent subject, since they possessed the essential twin attributes of colour and immobility.

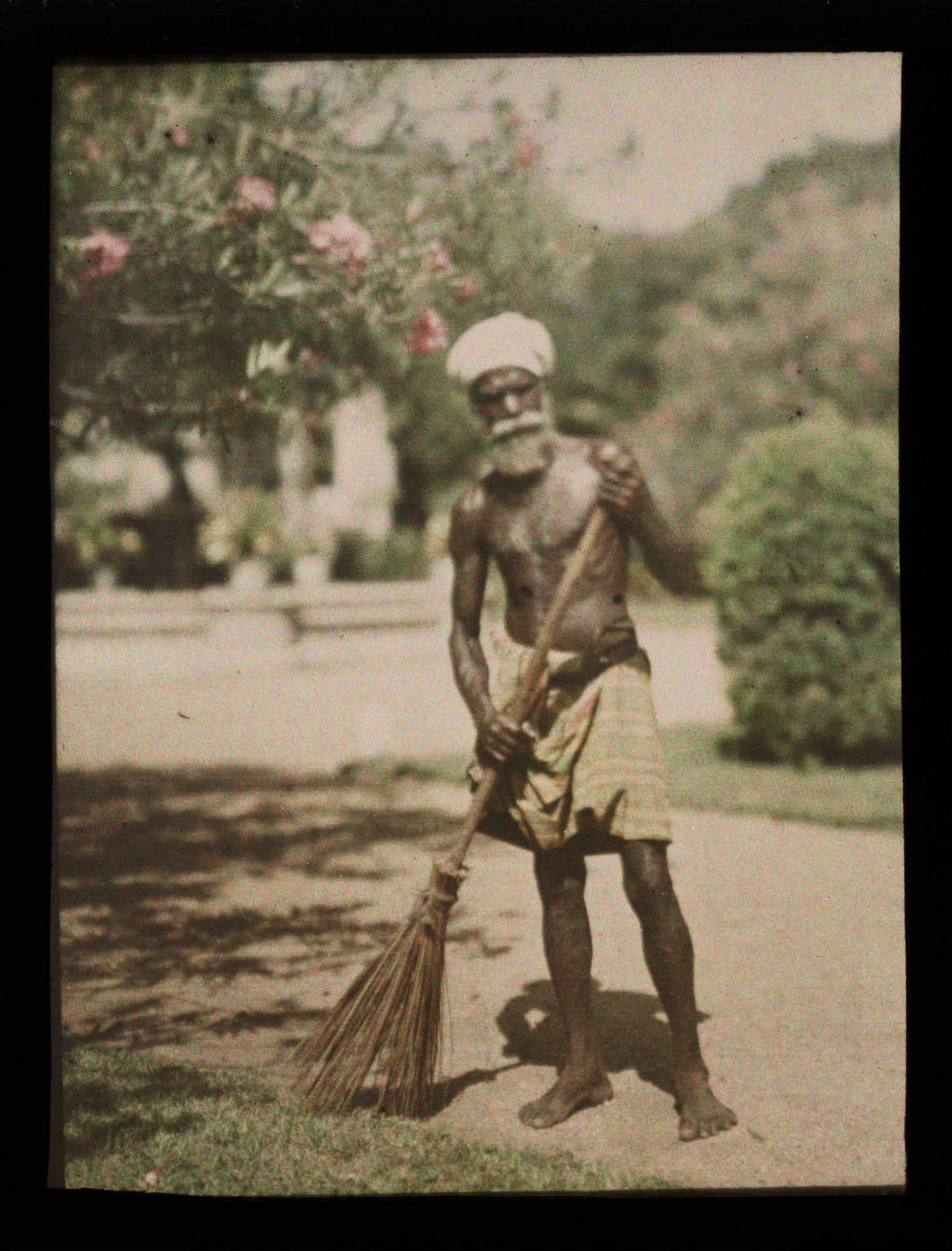

Photography’s potential as a means of documenting ‘reality’ had, of course, long been realised. However, the autochrome process brought a whole new dimension to the pursuit of realism—the recording of colour as well as form. The value of the process for scientific, medical and documentary photography was recognised almost immediately, and autochrome plates were widely used to photograph botanical and natural history specimens.

Kahn’s Archives de la Planète

Photography shapes our vision of the world and travel is one of the greatest motives for taking photographs. The ability to capture the world in colour was one of the major reasons for the popularity of the autochrome. Undoubtedly, the most extraordinary example of its use was the project initiated by the wealthy French banker Albert Kahn.

In 1909, Kahn decided to create his Archives de la Planète, described as:

… a photographic inventory of the surface of the planet as it is occupied, and managed, by man at the beginning of this twentieth century.

Kahn employed a team of photographers who were dispatched all over the world. The result, spanning over twenty years, was a collection of 72,000 autochromes taken in 38 different countries. While on an entirely different scale, of course, many wealthy amateur photographers followed Kahn’s example and used the autochrome process to record their travels all over the world.

The emergence of new processes

The success of autochrome plates prompted the appearance of several other additive colour processes, all based on the principle of a screen made up of microscopic colour filters. None of them, however, was as commercially successful and most are now long forgotten. Despite its limitations, the autochrome process dominated the market for colour photography for nearly 30 years.

In 1932, responding to a growing trend away from the use of glass plates towards film, the Lumières introduced a version of their process which used sheet film as the emulsion support. Marketed under the name Filmcolor, within a couple of years this had virtually replaced glass autochrome plates. However, these changes occurred at precisely the same time that other manufacturers were successfully developing new multi-layer colour films which reproduced colour films through subtractive synthesis—thus doing away with the need for filter screens. It was with these pioneering multi-layer films such as Kodachrome that the future of colour photography lay.

The autochrome was confined to history, but it retains its place as not only the first colour process, but also probably the most beautiful photographic process ever invented.

Bibliography

- Alfred Stieglitz, ‘The Color Problem for Practical Work Solved’, Photography, 13 August 1907, p136.

- The Photographic News, 6 March, 1908, p234.

- Robert Demachy, ‘The Pictorial Side in France’, Photograms of the Year, 1908, p62.

- R Child Bayley, ‘The New Colour Photography’, The Strand magazine, April 1908, pp412-4.

- The British Journal of Photography, Colour Supplement, 7 July, 1922, p28.

All the way through my infancy and early childhood in Virginia, my mother took photos of me & my sisters in black & white, and I continued this trend when I got my first camera at around age 10 as a Birthday Gift from my Aunt. I continued taking black & white photos all through elementary school, high school, and early high school, until Kodachrome was readily available. I remember debating with husband whether we should spend the extra money and buy color film for our vacations or special events, or limit ourselves to black-and-white film. Ironically, some of the most striking photos of architecture that I took during our early years in Chicago used black-and-white-film, and some pictures of gardens from my childhood would have looked so much more beautiful in color! I think I used to carry one roll of each type of film in my camera case, and I remember that, since I tended to take MORE than one shot of many subjects, the film of l2 pictures ran out pretty fast. Nowadays, it seems like ALL of my photos on digital are taken in color. I have never thought to set up my camera to take black-and-white photos, although that would be novel, and probably more creative. Now that I am taking a course in “The History of Photography” at Arizona State University Online, I can see that I may have missed a few opportunities to vary my color schemes, so that is a thought for the future! I am glad that my Professor posted this website to read as part of our assignment.

My camera was a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye (excellent prints!), followed by the Kodak Instamatic (photos not as sharp), followed by various Digital Cameras (Panasonic, etc.), and then a series of Digital Cameras in Cell Phones and Tablets. The Tablet photos ALL came out blurry except for a very few, but the Digital shots have been as good as, if not better than, the ones I took with my Brownie Hawkeye. Years ago, I also purchased a Video Camera (also Panasonic, I think), but when the Casettes stopped being manufactured, I was “stuck,” and a photo-processor told me he would charge me $300 to develop a Video I made of an Art Exhibit I hung at the Public Library in the town where I live. So I have never been able to have that developed, because that is more money than I can afford at this time! Someday, I hope to do that, but that won’t be until all my present bills are paid off in 2020 !! While reading about “The History of Photography,” I am struck by the fact that I have probably taken as many photographs as most of the famous photographers I have read about! Someone suggested that I organize an Exhibit of my Photos, but until I have some free time to organize them, that will also take place in “The Future! “

As a teenager in the late 1960s, I worked in our local camera store. An elderly lady brought a box in of old camera gear that her late husband owned. The cameras were interesting but I remember nothing of them. In the bottom of the box was a heavy package wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. When I untied the string and opened the paper, it took my breath away.

There must have been 25 or 30 5×7 Autochrome plates. Most in beautiful condition. I had just read about them a few weeks before so I instantly knew what they were. I could have bought them from her for $20 but that seemed like $500 to a broke teen at the time. I still kick myself for not scrounging up the money.

Is it possible to make autochromes today? We have potatoes and all the other things to make them, so why not?’

John Lambert

For anyone who’s interested Jonathan Tod Hilty is currently working on the autochrome process – checkout his instagram @amphetadreamer

I find it fascinating that in principle while the Autochrome is somewhat analogous to modern day photo sensors, modern layered films are more like the Sigma Foveon sensor. Yet the popularity of the formats is reversed.

things that I did not know. I was a photographer in the early 60,s

Can somebody tell me where to learn the autocrom processing to day ?

I would also love to know if there is some place to learn or at least experience doing this process once – I’ve been trying to research this process for some time and it is hard to find much information, let alone any demonstration of the process.

This might be exciting to some folks here:

Lumiere Autochrome plates were also produced in the US!

https://vermonthistory.org/lumiere-brothers-autochrome-photography

https://vermonthistory.org/journal/89/V8902LumiereNorthAmericanCompany.pdf