“The past was not a silent place”

—Dr Damien Murphy, University of York

The above notion is equally applicable to the future of the National Science and Media Museum and its planned galleries on sound and vision. As director Jo Quinton-Tulloch announced in her 2016 blog post, the museum’s new mission is to explore the science and culture of light and sound. As part of this vision, the museum has already launched Wonderlab, an interactive gallery exploring light and sound through mind-bending exhibits and live shows. Building on the success of this new interactive gallery, the museum is developing two new galleries designed to celebrate the science and history of light and sound technology.

Audiovisual technology is becoming more embedded into the fabric of our daily lives than ever before. Most of us own a smartphone or portable music-listening device, and streaming services such as Netflix have made watching TV at your own pace more popular than ever. Sound and light technologies are an unavoidable presence in all our lives; the new galleries propose to explore the different ways they have shaped the way we receive and consume audiovisual products. They will also focus on how we, the users, have harnessed this technology as a means of self-expression—and even shaped the way technology has evolved.

It is fascinating to explore the narratives behind the technological inventions that have made the presence of everyday products and platforms such as film, television, radio such a prominent fixture in our society. However, it is equally exciting—and perhaps even more important—that sound and vision technology is also viewed through the eyes of people that have bought, adapted and come to rely on this technology.

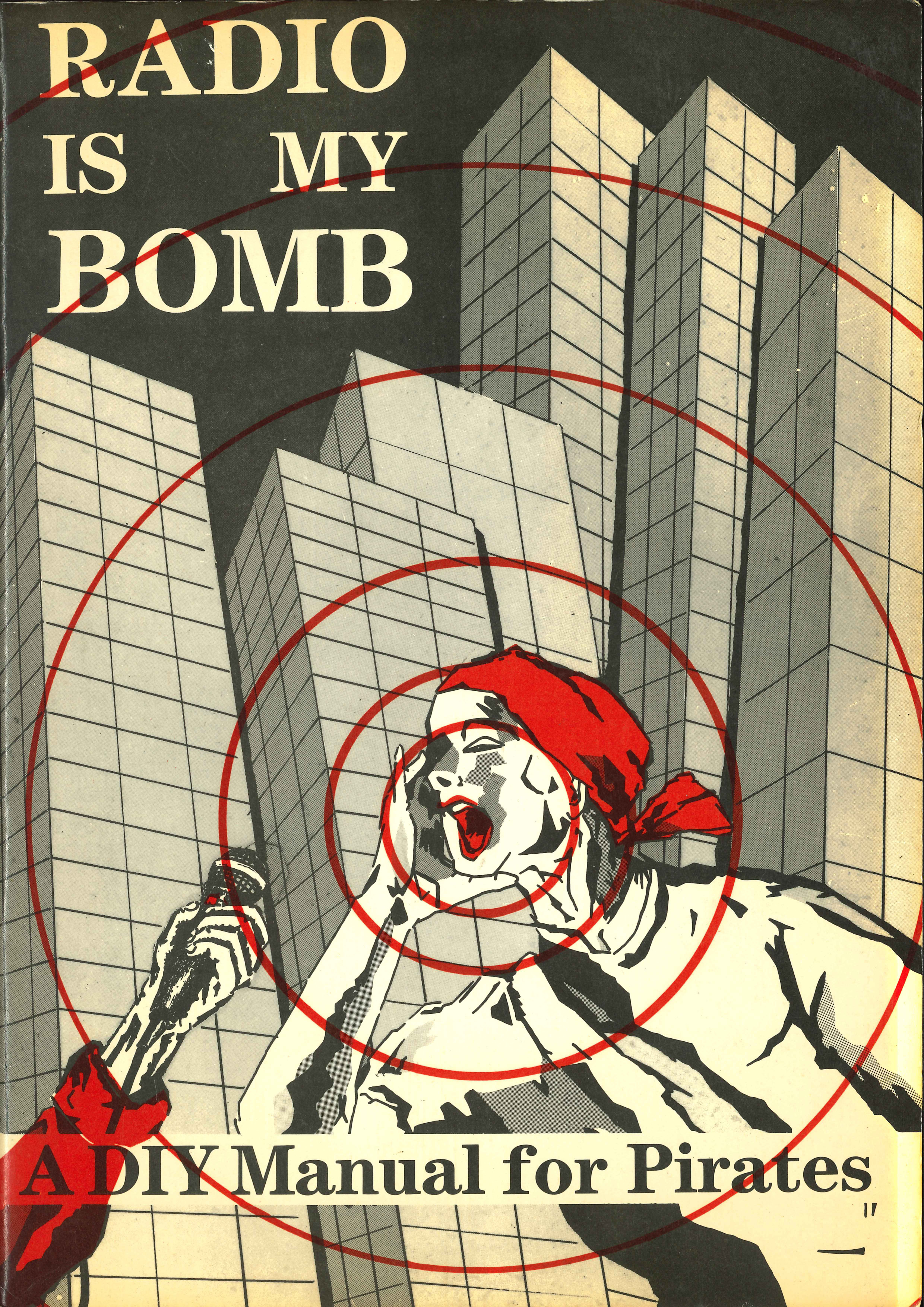

One sound technology narrative lies particularly close to the heart of Bradford: the innovative world of pirate radio. In the 1980s and 90s, pockets of cultural pioneers across the country used audio technology to hijack the airwaves in a bid to make their music and voices heard. Central to this story were the Bradford pirate DJs who created their own music broadcasting platforms, but also the wider Bradford community who supported these stations by providing a listening ear.

The history of pirate radio can be traced back to the 1960s when Radio Caroline famously exploited a legal loophole, broadcasting from the high seas in a bid to avoid government authorities. At the time, the BBC had a monopoly on radio broadcasting. Pop music was limited to just one hour per week. Bound by archaic legislation fashioned during the post-war years against the imagined threat of enemy broadcasting, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) had a zero-tolerance policy towards unlicensed radio stations.

Obtaining a government-issued community radio licence was a near-impossible task. Many pirates felt that there was no other choice but to embark on a drawn-out game of cat-and-mouse with the DTI, who continued to relentlessly persecute the pirates by raiding and confiscating their sound and music equipment.

With several pirate radio stations emerging in Bradford during the 1980s, many raids played out on the National Science and Media Museum’s doorstep, in locations such as Keighley and West Bowling. As a rich and multicultural city, Bradford is home to people with roots and connections to places from across the globe. However, in the 80s and 90s, strong dissatisfaction at the lack of cultural representation on local and mainstream radio airwaves prompted several members of the Bradford community to do something about it. Pirate radio stations provided a much-needed platform from which Bradford citizens could express and reflect the music and cultural identity of communities whose voices had been muted.

However, Bradford’s pirate DJs risked legal action for simply expressing themselves in a way that today, with easily accessible streaming platforms such as YouTube and Soundcloud, we often take for granted. For many of those involved, the goal was often simply to diversify what was heard on the radio and popularise the rich music enjoyed by Bradford’s diverse communities. As one pirate DJ commented in 1989:

“We are operating a service and trying to bring black, Asian and white communities together in friendship.”

Despite experiencing frequent raids where sound equipment was often seized, and the risk of prosecution, Bradford pirate radio stations were not deterred. They continued to broadcast from secret locations, resiliently bouncing back after each raid in a bid to continue their voyage of giving voice to their communities.

Speaking in 1988, one pirate radio manager reasoned:

“If we have to be a little bit illegal, then let us hope the result will be the same as it we were a little bit pregnant—that we get a fine healthy baby to care for.”

Hi Elaine ive heard there is a exhibition at the media centre about the pirate radios. i am going to go see it next week anyway thanks for the interview.All the the when you take your masters.Jerry