First presented in 1969, the MacRobert Award for engineering innovation has recognised some of the UK’s most creative engineers and the companies they worked for, whose cutting edge developments have not only enjoyed commercial success but also offered real benefits to society. The finalists for this year’s Award were announced on Saturday.

To mark the 50th anniversary of the MacRobert Award, the Royal Academy of Engineering commissioned conceptual photographer Ted Humble-Smith to interpret the engineering inspiration behind his favourite MacRobert Award winning innovations. The images are now on display in our online exhibition.

In this post, we take a look at the links between some MacRobert Award winners and the National Science and Media Museum’s mission to explore the transformative impact of image and sound technologies on our lives.

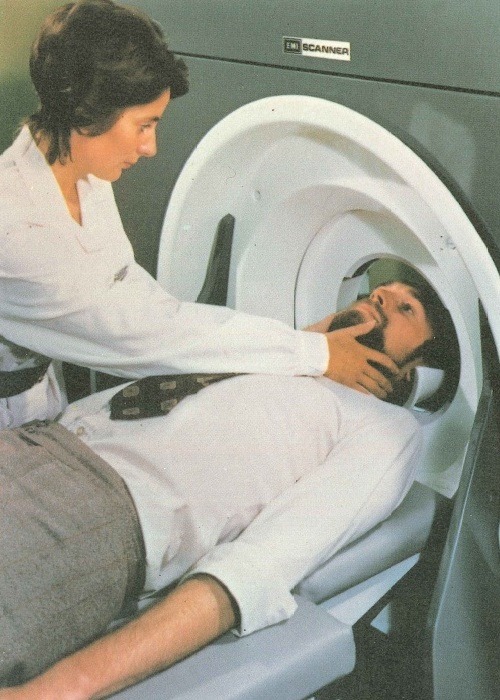

1. CT scanner

On 1 October 1971 the world’s first CT brain scan was performed on a patient using an EMI CT scanner, newly installed at the Atkinson Morley Hospital in Wimbledon (now part of St George’s Hospital). A year later, EMI Limited won the MacRobert Award for the application of X-ray techniques to diagnose brain disease. Designed by Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, the computerised tomography (CT) scanning technique constructed an image from measurements made by an X-ray source and a detector rotating around the patient.

The EMI CT scanner was the first production model to be used for trials on patients and was the first medical scanner to be adopted in substantial numbers. In less than 50 years CT scanning has become a key imaging technology that is used in hospitals around the world.

Sir Godfrey Hounsfield was born in Sutton-on-Trent in Nottinghamshire on 28 August 1919 and would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1979.

The first CT scanner is now part of the Science Museum Group collection.

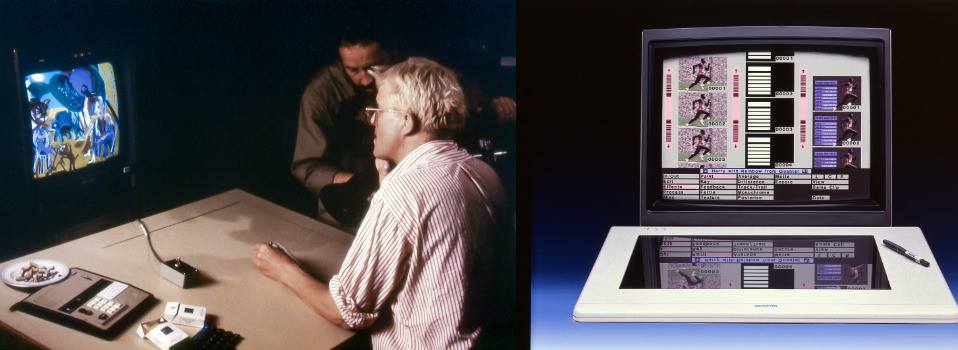

2. Quantel Paintbox computer graphics

David Hockney—who was born in Bradford and studied at the Bradford School of Art—was among the first artists to use the 1988 MacRobert Award winning Quantel Paintbox as part of a BBC programme called Painting with Light. David Hockney was so impressed with the innovation at the time that he felt it had applications beyond designing graphics, and described the experience as ‘painting with light on glass’.

Launched in 1981, Quantel Paintbox was years ahead of its time, boasting its own disc store and library management and using a touch-tablet and pen rather than a mouse. Fast forward to today and the pressure-sensitive pen is commonplace in every studio, but it was a world first for Quantel. Paintbox also pioneered the pop-up menu—a feature so intuitive and convenient that it is now taken for granted.

Broadcasters quickly started using Paintbox to create their weather maps, graphs, and title sequences. Together with Quantel’s Harry video editing system, Paintbox revolutionised graphics and video editing, resulting in some groundbreaking videos and album covers, including Queen’s iconic album cover for The Miracle and Dire Straits’ Money for Nothing video, voted the Video of the Year at the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards.

Quantel Limited received the 1988 MacRobert Award for the widespread impact of Paintbox.

3. Insight 100 airport security liquid scanner

When it comes to groundbreaking imaging technology, we naturally think of innovations that have propelled the broadcast industry or those that have enabled medical advances. However, imaging has also had a huge impact on global security. In 2014, Cobalt Light Systems (now Agilent) won the MacRobert Award for the Insight100 airport security liquid scanner, which was rapidly deployed at airports around the world as the threat of terrorist attacks increased.

Cobalt’s new technique was based on the work of the 1930 Nobel Prize winning physicist Sir Chandrashekhara Venkata Raman, who found that when light is shone on a material, a tiny part of its wavelength is scattered, creating a molecular fingerprint. Professor Pavel Matousek FREng and his colleagues developed a novel variant of Raman spectroscopy that can distinguish between the container and its contents, reliably identifying the chemical composition of a substance in seconds.

This non-invasive, through-barrier laser technique can analyse bottles of up to three litres to determine any threat, without having to open them. Throughout 2014, 65 airports across Europe—including Heathrow and Gatwick—went on to use the Insight100, and the upgraded Insight200m is now a common feature of airport security systems.

4. Microsoft Kinect human motion capture

As reflected in the museum’s collection, the gaming industry has been behind some amazing innovations. In 2011, this was recognised when the engineering team behind Microsoft Kinect won the MacRobert Award for their machine learning work on the human motion capture in Kinect for Xbox 360, allowing controller-free gaming. In the two months after its launch in November 2010, Kinect sold 8 million devices, making it the fastest selling consumer electronics device in history.

The Microsoft Research laboratory applied machine learning techniques to analyse depth images independently. It classified pixels in each depth image as belonging to one of 31 body parts, drawing on previous work from the Cambridge laboratory on the recognition of objects in photographs. The classifier was trained and tested using a very large database of pre-classified images, covering varied poses and body types. It was engineered so efficiently that it used only a fraction of the total available computing power—essential to the practical success of Kinect.

Kinect also found unexpected new uses; Microsoft came to consider non-gaming applications, such as robotics, medicine and healthcare, the primary market for Kinect—for example allowing surgeons to select images of patients without touching a page or a computer keyboard. Microsoft has also shrunk Kinect into a PC peripheral that can be used as a cloud-linked sensor.

You can experience the power of Kinect in an interactive exhibit in the museum’s Games Lounge.

5. Undersea cable plough

Sending texts or emails, turning on the TV or the radio and making phone calls are almost effortless extensions of our abilities to speak and communicate. These days, we rarely think of how much engineering goes into creating those connections, but in 1994 the MacRobert Award was presented to Soil Machine Dynamics (SMD) of Newcastle-upon-Tyne for the development of subsea cable and pipeline ploughs capable of digging and burying the intercontinental cables that enable the world’s communications systems.

SMD pioneered the world’s first undersea cable plough. For over 45 years they have designed and supplied ploughs, trenchers and remotely operated vehicles for use by offshore telecommunications operators, as well as the oil and gas and renewable energy industries. Their towed systems are designed to bury subsea telecommunication and power cables of up to 350mm diameter and pipelines of up to 1500mm diameter.

Read more about the history of cable laying in this Science Museum Group story: How perseverance laid the first transatlantic telegraph cable. And don’t forget to check out the full online exhibition.