We return to our alphabetical tour of our collection with a stroll through George Davison’s onion field.

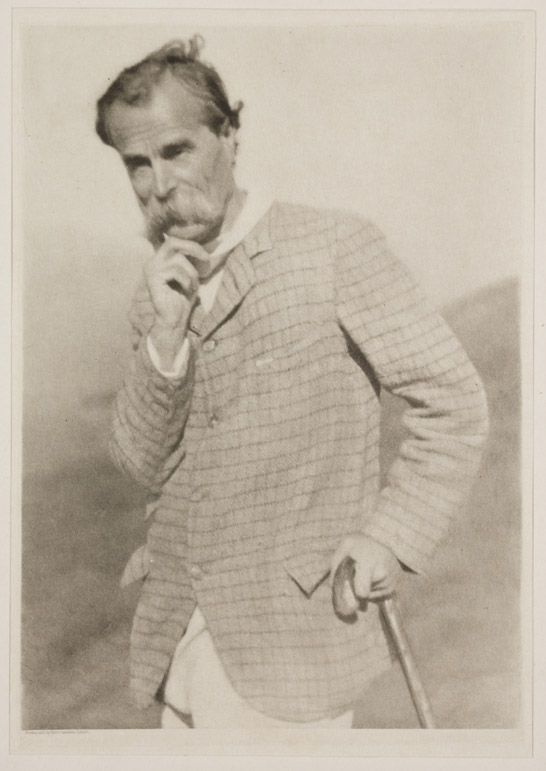

George Davison (1854–1930) was one of the most important figures in the development of pictorial photography at the end of the 19th century. He exhibited widely and was one of the founding members of the Linked Ring, a society dedicated to the furthering of artistic photography.

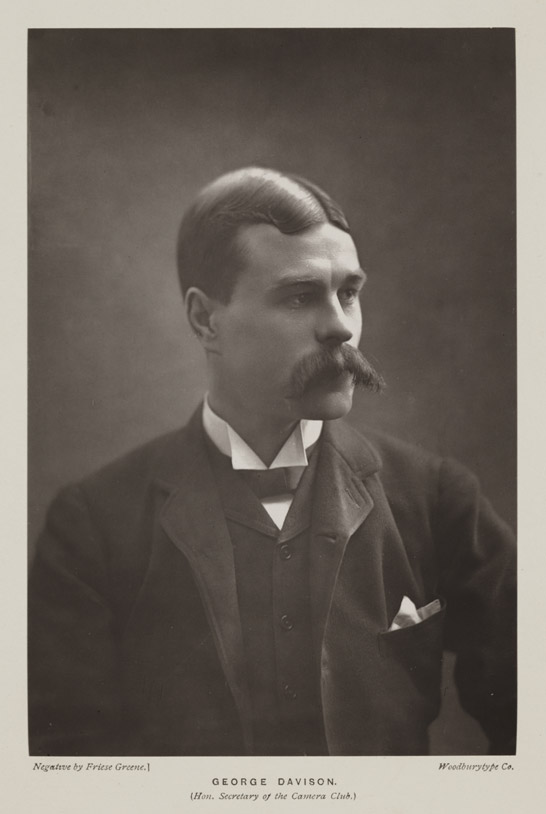

Born in Lowestoft, Suffolk, he came from a modest background and was the only member of his family to receive a secondary education. Davison first took up photography in about 1885, becoming a member of the Camera Club that year and the Photographic Society the following year.

In his efforts to achieve the impressionistic, painterly effect which he desired, Davison experimented widely with different techniques and processes.

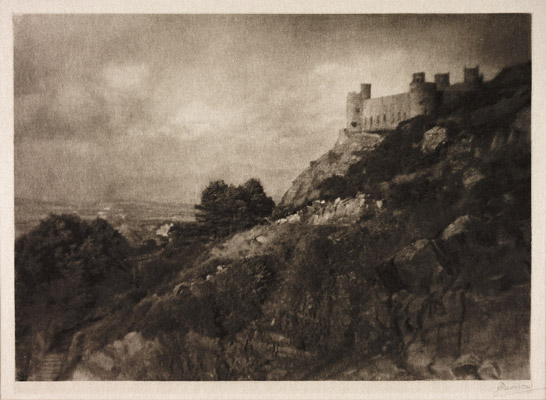

In 1890, one of his photographs, An Old Farmstead (also known as The Onion Field), taken with a pinhole camera and printed on rough paper, was awarded a medal at the Photographic Society of Great Britain’s annual exhibition.

Davison was one of the first to exploit the technique of pinhole photography for pictorial effect and over the next few years his exhibition entries generally included pinhole images.

When it appeared, The Onion Field created enormous interest. In its review of the exhibition, The British Journal of Photography began by discussing Davison’s controversial medal-winning exhibit:

This photograph will probably be the battle-field for the two conflicting sections of photographic art which the progress of time has brought so prominently forward.

The battle was between those who championed ‘straight’ photography and those who explored a more impressionistic aesthetic—often summed up as ‘fuzzy’ photography.

It was clear which side the reviewer in the BJP was on:

The normal condition of eyesight is to see distinctly, when it is not so there is a defect. Photography has so many good artistic capabilities that it is to be regretted that works like this one should prevail, which evincing much, very much, so artistic in conception, should be, as we think, jeopardised by so marked a departure from the accepted outcome of photographic research.

In its review, The Amateur Photographer magazine also noted the contemporary trend towards impressionistic effects:

Perhaps the chief feature of the present collection is the evidence it gives of the marked advance and influence of what may be termed the ‘school of foggy photography’.

The exhibition was also reported widely in the general press. The Times tried hard to be impartial in the debate over ‘fuzzy or sharp’:

The question is not easy of decision, perhaps will never be decided. Those, however, who care to judge for themselves have an excellent opportunity of doing so now, for on the walls of the gallery are many admirable—and some not particularly admirable—examples of both schools.

According to The Times, Davison’s work clearly fell into the ‘admirable’ category:

Perhaps no more beautiful landscapes have ever been produced by photographic methods than Mr. Davison’s Old Farmstead and Breezy Corner, to the former of which a medal has been given. In this one especially atmospheric effect is admirably rendered, and, looked at from a suitable distance, the picture gives a wonderfully true rendering of the subject, combining in large proportions the broad effect resulting from skilful artistic treatment with the actual truth in detail of a photograph.

Not all reviewers, however, were so positive. The Globe magazine, for example, commented:

One feature in the show is sure to excite wonder in the minds of many of the visitors, especially with those unacquainted with the present photographic craze. It is that the majority of the Society’s medals should have been presented to faded-looking ‘fuzzy’ pictures, out of focus, and generally indistinct; printed on sensitised rough drawing paper. There are an abundance of pictures that will seem to the many far more worthy of these distinctions, and it is exceedingly doubtful whether the present craze will find many admirers among the general public.

As Davison’s photographic career took off, he was also to enjoy financial success.

In 1889, George Eastman had invited Davison to become a director of the newly-established London branch of the Eastman Photographic Materials Company.

Davison bought 25 shares at £10 each, using money borrowed from a friend. It was an investment which was to prove extremely profitable. This was the beginning of Davison’s long association with George Eastman and Kodak.

In 1897, he left his job as a civil servant in the Audit Office to become assistant manager of the Eastman Photographic Materials Company.

To promote the company’s products, Davison gave away free Kodak cameras and film to his photographer friends in return for permission to use their pictures for advertising purposes. These included very well-known figures such as Paul Martin, Eustace Calland, James Craig Annan and, most prolifically, Frank Meadow Sutcliffe.

In 1898, Davison became Deputy Managing Director of Kodak Limited. With an annual salary of £1,000 and owning thousands of shares in the company, he was now an extremely wealthy man. The sudden death of the managing director, George Dickman, resulted in Davison becoming Managing Director in 1900—a position which brought him both affluence and influence.

Despite his growing business responsibilities, Davison continued to take photographs and to exhibit his work. He was, however, becoming increasingly preoccupied with other matters.

Undoubtedly stemming from his humble origins, Davison had a life-long interest in social reform. Although more of a committed Christian Socialist than an anarchist in the Marxist sense, he was associated with several anarchist organisations. His political activities made his position untenable in Eastman’s eyes and in 1912 he was forced to leave the company.

Davison moved to Harlech in North Wales, where his splendid house became a focus for artistic and political gatherings. As his health declined in the 1920s, he spent more time at his home near Antibes in the south of France, where he died in December, 1930.

Further reading

- Brian Coe, ‘George Davison: Impressionist and Anarchist’ in Mike Weaver (Ed), British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, pp 215–241.

- ‘The Photographic Society’s Exhibition’, The British Journal of Photography, October 10, 1890, p.645.

- ‘Exhibition of the Photographic Society of Great Britain’, The Amateur Photographer, October 3, 1890, p.236.

- ‘Opinions of the London Press on the Photographic Exhibition’, The British Journal of Photography, October 3, 1890, p. 632.

4 comments on “O is for… The Onion Field and the great ‘fuzzy’ photography debate”