For the first instalment of my Photographic A-Z, I wrote about Frederick Scott Archer’s invention of the wet collodion process on glass in the 1850s. However, no sooner had glass replaced paper or metal as a support for light-sensitised emulsions, than photographers began to look for a practicable alternative.

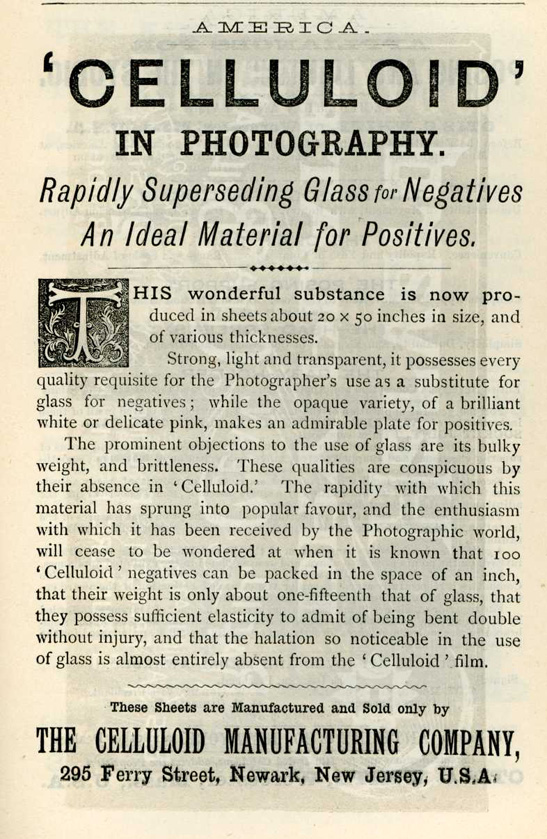

The problem with glass was that it was bulky, heavy and fragile. Any substitute would have to be light, tough, flexible, unaffected by water or chemicals and, of course, transparent. The answer lay in one of the most important synthetic materials developed in the nineteenth century—cellulose nitrate, better known as celluloid.

The origins of celluloid

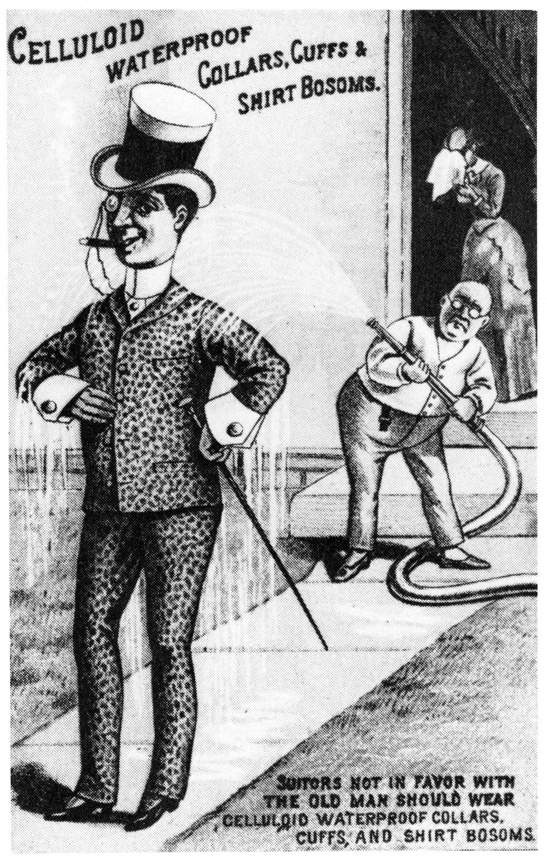

Celluloid has its origins in the work of an Englishman, Alexander Parkes. In 1855, Parkes was granted a patent for a substance which he called Parkesine produced using a mixture of oils and gums as a solvent for nitrocellulose. In America, brothers John and Isiah Hyatt discovered that camphor under heat and pressure acts as a nitrocellulose solvent. They called their new material celluloid and in 1872 they founded the Celluloid Manufacturing Company which made a range of products from celluloid, such as dominoes and billiard balls.

The development of celluloid in photography

As celluloid became better known, its qualities recognised and its use as a substitute for other materials widened, photographic experimenters became increasingly interested in its possibilities. A number of people attempted, unsuccessfully, to promote the use of sheets of celluloid as a substitute for glass plates, including David and Fortier in France and Waterhouse in England.

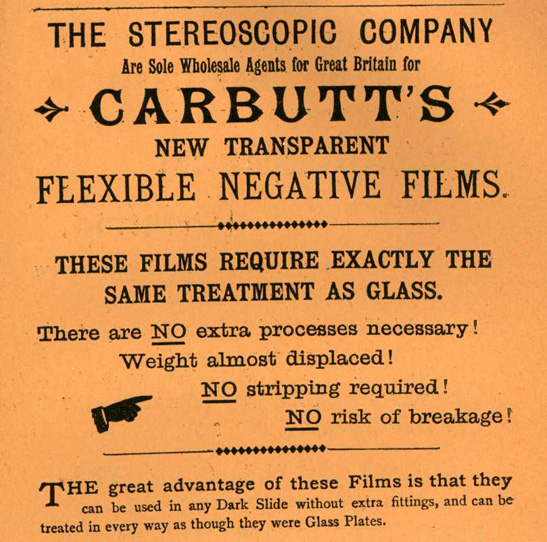

The breakthrough came in 1888 when John Carbutt, an Englishman born in Sheffield who had emigrated to America as a young man, put on the market the very first commercially produced gelatin emulsion-coated celluloid sheet film. Although marketed as ‘flexible negative film’, Carbutt’s celluloid sheets were, in fact, relatively stiff and unsuitable for production in long strips for use in rollholders.

In 1887 Hannibal Goodwin, a relatively unknown clergyman and amateur photographer in Newark, New Jersey, filed an application in the US Patent Office for a ‘transparent sensitive pellicle better adapted for photographic purposes, especially in connection with roller-cameras.’

Goodwin was a self-taught chemist and his patent application was broad and somewhat ambiguous in its wording. For two years, the application remained unissued, undergoing several amendments, but by this time other inventors, most notably George Eastman and his chemist Henry Reichenbach had entered the field.

Goodwin Film and Camera Company vs Eastman Kodak Company

In 1888, the year that he introduced the Kodak camera, George Eastman began to seriously explore the possibility of manufacturing flexible rolls of sensitised celluloid. He set his young research chemist, Henry Reichenbach on the task and the following year both Eastman and Reichenbach filed patent applications for flexible celluloid film. These interfered with Goodwin’s application, filed two years earlier, setting in motion a legal battle that would drag on for over twenty years.

Eastman’s celluloid film went on sale in the autumn of 1889 and was available in a range of sizes to fit the various rollholders and the growing range of Kodak cameras (four different models by this time). The commercial potential for rollfilm was enormous, as Eastman quickly realised. In March 1889 he had written to his business partner William Walker:

The field for it is immense… If we can fully control it, I would not trade it for the telephone.

Eastman did not enjoy a monopoly of film manufacture but his company did come to dominate the market. Throughout the 1890s, boosted by the rapid growth of amateur photography and its use in cinematography, transparent celluloid rollfilm was produced in ever increasing quantities. All this time, Goodwin’s patent application remained under consideration. It was not until 1898, eleven years after his original application had been filed, that Goodwin was finally granted a patent.

After his death in 1900, Goodwin’s patent was sold to the American firm of Anthony and Scovill, who took out a suit against Kodak for patent infringement in 1902. The case dragged on for over ten years and, finally, in August 1913 it was ruled that Goodwin’s patent had indeed been infringed:

not on the ground that Eastman had copied the process, but that Eastman’s process, though an improvement, came within the Goodwin patent claims.

The following year, Eastman paid his competitor five million dollars as compensation. A huge amount, but tiny when compared to the profits that Eastman had earned from sales of celluloid film in the intervening years.

Further reading and interesting links

- Video: George Eastman—The Wizard of Photography, part 3 of 3 (PBS Documentary)

- Exploding Teeth, Unbreakable Sheets and Continuous Casting: Nitrocellulose from Gun-Cotton to Early Cinema, Deac Rossell (2002)

- Reese V. Jenkins, Images and Enterprise: Technology and the American Photographic Industry, 1839 to 1925. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

- Roger Smither and Catherine Surowiec (eds.), This Film is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film, Brussels, FIAF, 2002.

2 comments on “C is for… Celluloid: The Goodwin vs. Kodak patent battle over flexible film”