The 1960s saw massive upheaval across America, with the fight for civil rights, the growing anti-war movement, and other campaigns for social justice. As the counterculture bloomed and public dissent took hold, societal tensions were reflected in the rise of a new, daring cinematic movement.

Starting in 1967 with Bonnie & Clyde, the movement would become known as the New Hollywood. It turned its back on the costly studio musicals and historical epics of the 1950s, ushering in independent films helmed by young directors like Martin Scorsese and William Friedkin. The films were raw and violent, and challenged conservative views. They suggested a more radical future was available to the young audiences that flocked to the movie theatres.

Screening at Pictureville from 16 September, the new film season Look Who’s Back: The Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist aims to reassess the key influences behind this historic period of cinema. Screening classics like Serpico, M*A*S*H, and Midnight Cowboy, the season considers how the old Hollywood guard, blacklisted in the 50s, made a vital contribution to the reinvigoration of cinema in one of Hollywood’s most creative eras, and were just as influential as the young directors that would take the spotlight.

What was the Hollywood blacklist?

The Hollywood blacklist was an attempt to counter communist influence in American culture. It began in the years after the end of World War II when some of the USA’s former allies, particularly the Soviet Union, now became enemies.

A group of perceived communist supporters known as the Hollywood Ten were jailed, while another 151 actors, writers, musicians and broadcast journalists were named as communist sympathisers. This led to many being called before the newly formed House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and the blacklisting of those who refused to collaborate.

As the 1950s progressed many of those blacklisted, including writers and composers, were forced to work under pseudonyms or fronts. For some directors and actors the blacklist led to either exile or inactivity, with many not being able to work in America again until the 1960s.

In the 1960s the blacklist began to break down after the release of two films written by Hollywood Ten member Dalton Trumbo, Exodus and Spartacus, and exiled figures came back into the fold. Influenced by the turmoil of the 1950s, these creatives returned to Hollywood with renewed vigour, fuelling a run of critically acclaimed, politically charged features that would reflect the turbulent times they lived through, finding fresh collaborators in the youthful and radical voices within the New Hollywood era.

Four faces of the blacklist

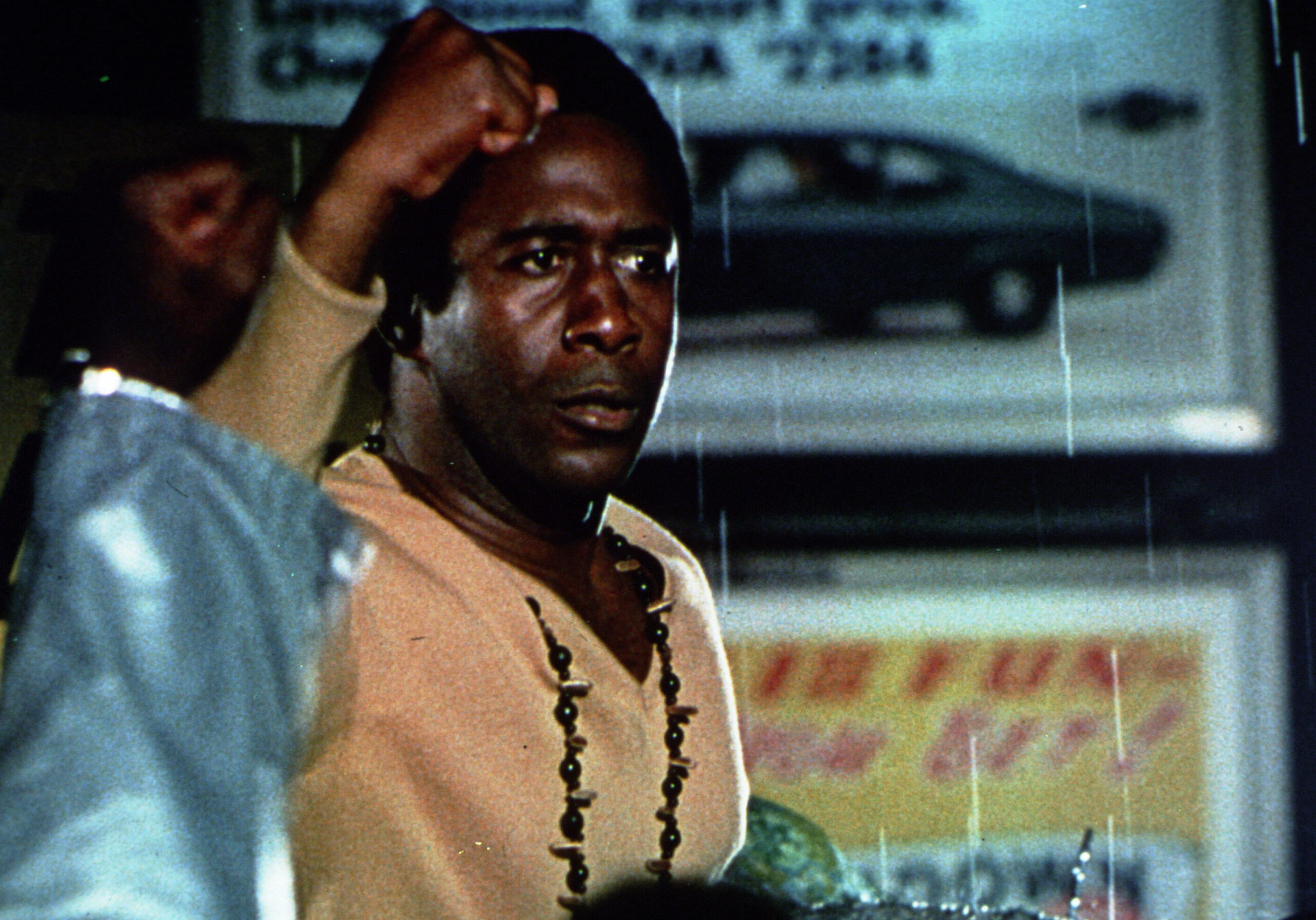

Jules Dassin – Director of Uptight (1968)

Dassin had been blacklisted in the 1950s for his activism and communist sympathies. After exile in Europe (where he directed films in France and Greece), he returned to Hollywood with his 1968 classic Uptight. Set in the aftermath of the assassination of Martin Luther King, the film features all the political urgency expected of the era, with a script written in collaboration with activist Ruby Dee. Even during production Dassin couldn’t escape controversy, and some Uptight crew members acted as informants to the FBI, who closely monitored the making of the film.

John Berry – Director of Claudine (1975)

After shooting a documentary about the Hollywood Ten, Berry was exiled to France and named as a communist. He kept in work by shooting the last Laurel and Hardy film, Atoll K, and returned to Hollywood in the 60s with some American Television, and eventually returned to American cinema with the remarkable, powerful drama Claudine.

Ring Lardner Jr. – Screenwriter of M*A*S*H (1970)

Jailed for 12 months for contempt of Congress after refusing to testify in front of the HUAC, Lardner Jr. returned to Hollywood in 1965 with a credit for The Cincinnati Kid and would win an Academy Award for M*A*S*H, a satirical dark comedy set in the Korean War and directed by legendary auteur Robert Altman.

Waldo Salt – Screenwriter of Serpico (1973) and Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Unlike many targeted by the blacklist, Waldo Salt recovered triumphantly. After refusing to testify in front of HUAC in 1951, Salt had to write under a pseudonym for years until his reintegration in the late ‘60s. His screenplays for Midnight Cowboy and Serpico show his commitment to themes of corruption and injustice, casting an empathetic light on the underdog. Salt won an Academy Award for Midnight Cowboy, and a second win in 1978 for Coming Home suggested a full embrace of the once-exiled figure.

Though these creatives had acclaimed works in the New Hollywood era, the blacklist would forever define a huge part of their lives, and their own personal turmoil informed the passionate fury of these iconic films. Look Who’s Back is a vital cinema season that offers the chance for audiences to see these shocking, challenging masterpieces on the big screen.

Look Who’s Back: The Hollywood Renaissance and the Blacklist begins with Serpico on 16 and 17 September. For tickets to the full season, visit our website.

The season is presented as part of Cinema Rediscovered on Tour, a Watershed project in partnership with Park Circus. With support from BFI awarding funds from The National Lottery and MUBI.