Dagron Microphotographic Camera

Chosen by Ruth Quinn, Curator (Photography and Photographic Technology)

Possibly the most surprisingly heavy camera in the Kodak Gallery, this brass contraption is for taking tiny photographs. Designed by René Dagron in the 1860s, the camera was used to produce multiple ‘microphotographs’. Dagron pioneered the use of photomicrographs both for decorative and secretive purposes.

Through developing a special kind of viewer, Dagron had a lucrative trade in the production of ‘Stanhopes’, which are small pieces of jewellery inset with a photomicrograph that can be viewed at a certain angle. There are a number of these curios on display next to the camera in the gallery.

Alongside these more public uses of the technology, Dagron also recommended the use of photomicrographs for carrying secret messages. In the 1870s, he developed a system for attaching a quill containing a roll of microfilm to a messenger pigeon to aid French military intelligence.

Stirn Waistcoast Detective Camera

Chosen by Hayley Bruffell, Archives Cataloguer

My favourite item from the Kodak Gallery is the Stirn waistcoat detective camera, a disc-shaped metal contraption which is thin enough to be worn beneath a waistcoat whilst hung from the photographer’s neck by a strap. The lens would poke through the buttonhole and was designed to look like an ornamental button whilst a piece of string, which would have been hidden in the trouser leg pocket, would be pulled to take the picture. Six photographs could be taken on a circular glass plate which would be rotated after each exposure by turning a knob on the front of the camera. How the photographer managed to turn the knob discreetly is another story!

The introduction of commercially manufactured gelatine dry plates in the late 1870s greatly improved exposure times and made ‘instantaneous’ photography possible for the first time. This ability to take spontaneous and candid photographs without the subject’s knowledge reflected the developing dramatic changes in photographic technology and a new attitude towards what photography could be as a medium, as well as new concerns around surveillance and privacy! By the 1890s, over 18,000 of the cameras were sold but they were eventually left behind by a rapidly evolving medium which rendered items like these obsolete.

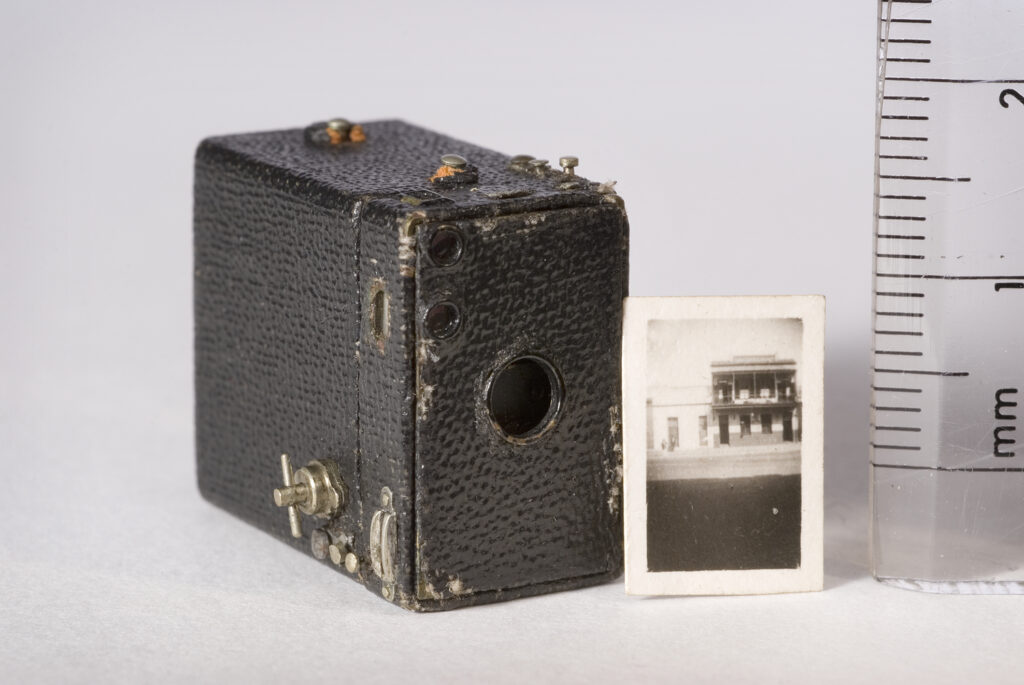

Miniature Scale Model of 2C Brownie camera, negative and print

Chosen by Vanessa Torres, Conservator

Following on my love from everything tiny, this miniature scale model of a No. 2C Brownie camera is my favourite gem on display in the Kodak gallery.

This camera, measuring just 20mm x 10 mm x 25 mm, was made by the Kodak technicians for Queen Mary’s doll’s house project in 1924. It was a fully functioning camera able to capture the whereabouts of the family and their surroundings. In its showcase dedicated to ‘Photography and Royalty’, a negative and contact black and white photograph can be seen alongside the camera. How irresistibly little!

Thompson’s Revolver Camera

Chosen by Lewis Pollard, Curator (Television and Broadcast)

This camera was inspired by a revolver gun. The aim was to make it effortless to take a picture with a single hand holding the grip and aiming it like a pistol. In reality this led to blurred images and no-doubt frightened subjects, so it never caught on. However, this is not the last time that guns would inspire camera design!

No. 2 Brownie Model F Camera

Chosen by Ellie Durrant, Conservator

The shop display styling of the No. 2, Model F Brownie cameras in the Kodak gallery appeals to me every time I walk past. With the holiday season just past, gift giving has been on my mind, and how lovely would it have been to have received a colourful camera like this in the early 1900s? The smart finish, the linework detailing, and the compact nature of it all definitely appeal. Studying the design more closely, its remarkable how similar modern smartphone backs are to the front of this camera!

With the rise of modern versions of vintage style cameras, I can’t help thinking, will we see some revamped Model Fs back on the shelves very soon?

Steineck ABC Wristwatch Camera

Chosen by Saquib Idrees, Assistant Curator

The Steineck ABC wrist-camera is one of my favourite objects in the Kodak gallery. It is a small camera built to take six 3x4mm photographs, but designed to look like a wristwatch. This camera was mostly a novelty item considering how small the photos taken were and due to the photographic technology on the watch face, it lacks the ability to tell the time despite its excellent disguise. Though I do enjoy the thought of someone asking the wearer of this watch “what time is it?”, priming them to respond with, “time to take a photograph!” to which they both laugh and pose for a watch selfie.

Seagull

Chosen by Alex Greenhough, Documentation Officer

Sometimes it’s the small details in museum displays that make all the difference. This beach diorama in the Kodak Gallery shows us a photographer at the seaside—so different from how we might simply snap a photo on our phones nowadays. But it’s the little things in the scene that help us imagine ourselves there, on the sand in the sunshine.

Next time you’re in the gallery, look out for the donkeys, a family having a picnic, the sandcastles and—my favourite—the seagull! These details bring the sights, sounds and smells of the seaside to mind, bringing the scene to life, and they are all things that we might see at the seaside now. Certainly snapping a seaside photograph would have been very different over a hundred years ago, but a trip to the beach was probably very much the same—people still played in the sand and built sandcastles. And the seagull reminds us that, even back then, there was a very real risk that one might pinch your lunch!

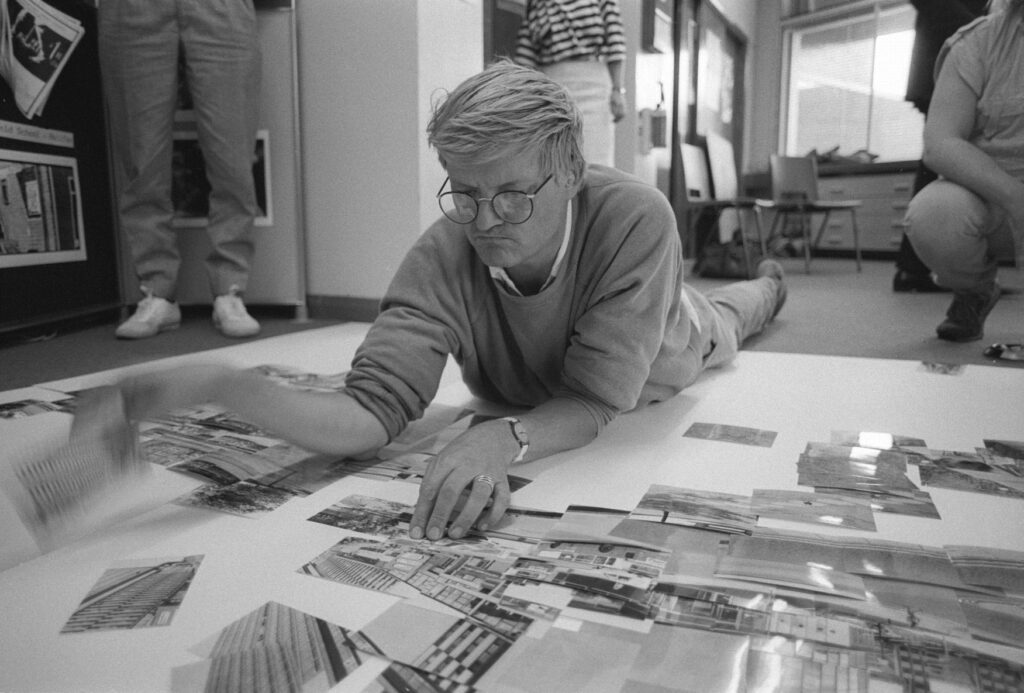

David Hockney’s ‘Joiner’

Chosen by Rebecca Marrows, Conservation Manager

My current favourite object on display is an artwork called ‘joiner’ created by David Hockney which has been installed in the exhibition David Hockney: Pieced Together. The artwork is a photo-collage of the National Science and Media Museum, made from photographs taken in 1985. Alongside this, images of David Hockney creating this artwork can be seen, including seeing how he took the photographs. It’s not always possible to see the behind the scenes of artists creating their work.

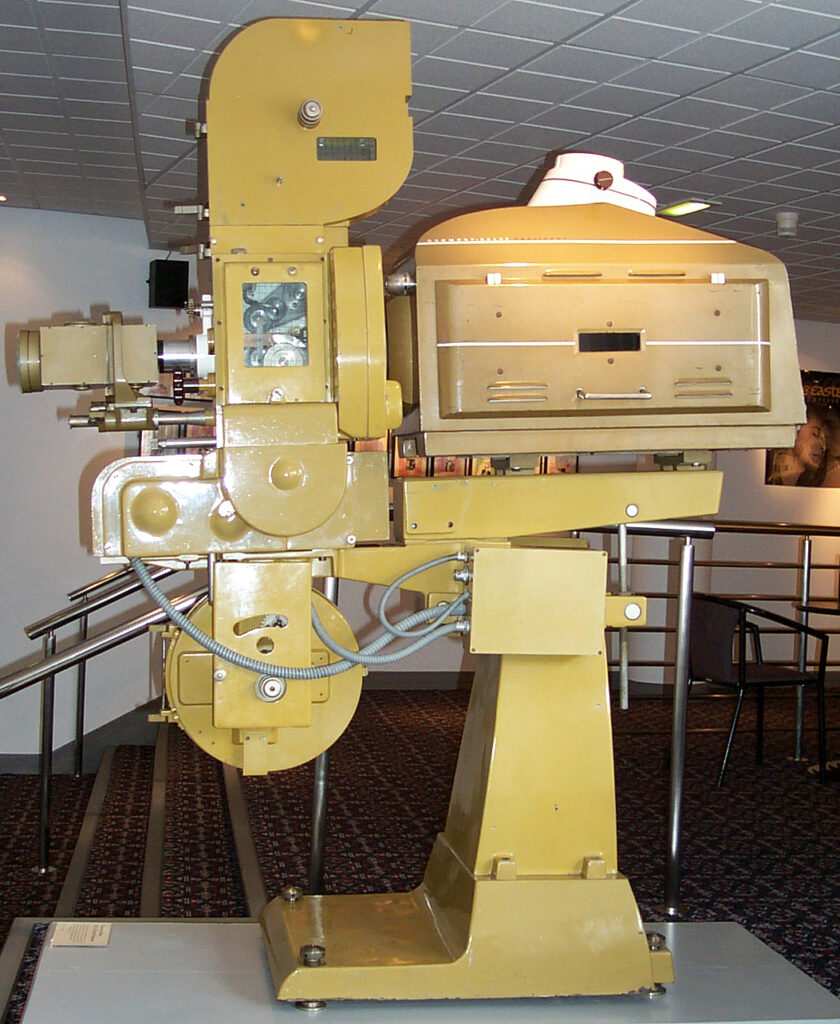

Gaumont-Kalee GK21 35mm film projector

Chosen by Toni Booth, Curator (Film)

Whilst all of our museum objects are important and have stories to tell, sometimes you can’t beat a really big one for impact and if it’s yellow and has a proper Yorkshire heritage so much the better. Taking pride of place in our Pictureville Cinema foyer is this Kalee GK21 35mm film projector, which has been on display since the cinema opened in 1992.

This projector provides a connection between the history of cinema technology and Yorkshire industry and the contemporary presentation of film. The museum still has working analogue film projectors sitting alongside the newer digital versions in our projection booths.

The GK21 was manufactured by the Leeds-based company A Kershaw and Sons Ltd in 1947. At their height, Kershaw’s employed 3000 people and claimed that 75% of British cinemas used their projectors. The business was established in Leeds in 1888 by Abram Kershaw. They initially made and repaired scientific equipment and began to produce photographic equipment in the early 1900s. Two of their Soho Reflex cameras were made for Herbert Ponting to take with him in his role as the official photographic officer of the British Antarctic Expedition led by Captain R F Scott between 1910 and 1913.

Kershaw’s produced cinema projectors under the Kalee trade name from the 1910s. The name came from the initials of Kershaw, A, Leeds. During WW2, as well as undertaking governmental contracts, Kalee continued to produce cine equipment and joined with Gaumont British, who owned hundreds of cinemas across the UK (they also funded the building of the New Victoria cinema in Bradford, later known as the Odeon and now Bradford Live) to form GB-Kalee Limited to sell projection equipment. The GK21 projector was one result of this partnership.

The bright colour of the projector (most earlier ones were simply black) was suggested as a way to counteract the claustrophobic environment of the projection room. In addition, to promote projectionists’ attention for cleanliness, the interior of the mechanism was painted white to show even the smallest speck of dirt.

Ultimately, A Kershaw and Sons was acquired by the Rank Organisation, largely so that Rank could have an in-house provider of equipment for its large chain of cinemas. They were instructed to drop all other work to fulfil the technological needs of over 1000 cinemas to upgrade to the new Cinemascope process.

These large projectors were primarily used for cinemas which had over 2,000 seats, and this one eventually came back to its home city, ending its working life at the University of Leeds before becoming part of the museum’s collection.

The National Science and Media Museum is open daily, 10.00–17.00. You can book free admission and find out more about what’s on at our website.

I worked as projectionist at The Regal Cinema Edmonton in the 60’s and 70’s and we had two full Kalee 21’s which ran without any problems due to the long throw they were fitted with Mole Richardson Arcs then were changed for Cinemeccania Super Zenith Arcs it was the best job I ever had and I really enjoyed it