When it comes to live events, especially sporting ones, speed is of the essence. Getting pictures to an audience, if not immediately, then as soon as you possibly can is very, very important. If a film-maker or television company is able to do this, it immediately puts them ahead of their competitors—gaining a little piece of the glory along with the sportsmen and women on the pitch, ground or track.

However, there are significant technological and industrial challenges to be overcome, not to mention certain added complications if the event you wish to capture takes place over a race track which is 4.2 miles long and not on dry land.

Of course, I am referring to the University Boat Race which was first staged in 1829 and became an annual event from 1856. It has always been a popular event, with thousands lining the route along with large radio and television audiences. In 2018, 4.8 million viewers watched the women’s race and 6.2 million the men’s race on BBC television. I always found this slightly baffling when it is such a closed shop. I might be a little naïve, but I like to think that in most sporting events the ‘best’ get to compete irrespective of who they are or where they come from, but there’s an obvious additional excluding factor in the Boat Race. However, this may point to it being one of those events (along with the Grand National?) which actually transcends its sporting basis. To those who watch it, it marks a moment in the annual calendar, a sense of tradition (and British eccentricity?) and of course, an opportunity to have a flutter.

This popularity made it a natural event for the BBC to cover and they began to broadcast the Race live on radio in 1927 and live on television from 1938 (with a small gap from 2004 to 2009 when ITV were given the job), making this year the 80th anniversary of the first BBC TV broadcast of the Boat Race.

However, that initial BBC broadcast in 1938 might have disappointed modern viewers a little, as most of it consisted of John Snagge’s radio commentary illustrated by a chart along which magnetised boats were shuffled in synch with the voice over, showing viewers where the boats were along the route. But the true treat—and the first time any image of the Boat Race had been seen live by anyone not standing on the riverside—came at the end, when the finish was transmitted live and direct to anyone fortunate (or wealthy) enough to have a television. (It is estimated that there were 20,000 television sets in the UK in 1939 when BBC television closed down at the advent of World War II).

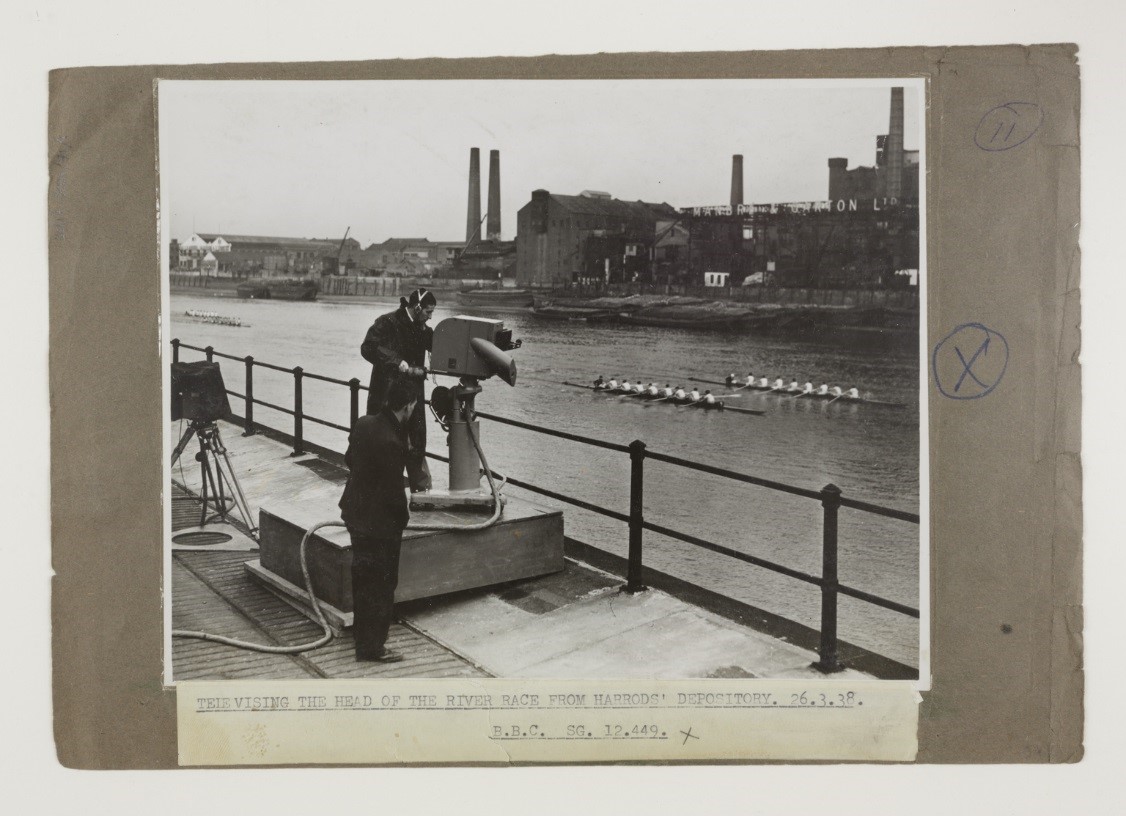

Here you can see one of the Emitron cameras that the BBC were using for the broadcast outside the Harrod’s Depository building, one of the landmarks along the route. Emitron cameras were developed in the UK from 1933 by EMI, who won the competition to provide the BBC’s first regular high-definition television service from 1936. Shortages of money and resources in the post-war period meant that these Emitron cameras remained in regular use well into the 1950s.

It was not until 1949 that the whole of the race was broadcast live on BBC television, with eight shore-based cameras along the route and one in a launch following the action.

Although at this time, the image quality of television could not match that of film, the benefit of television is, of course, the immediacy of the images. Prior to this, audiences had to wait to see the action, by which time it was possible that someone had already let slip who had won the race or had found out the outcome from the newspapers.

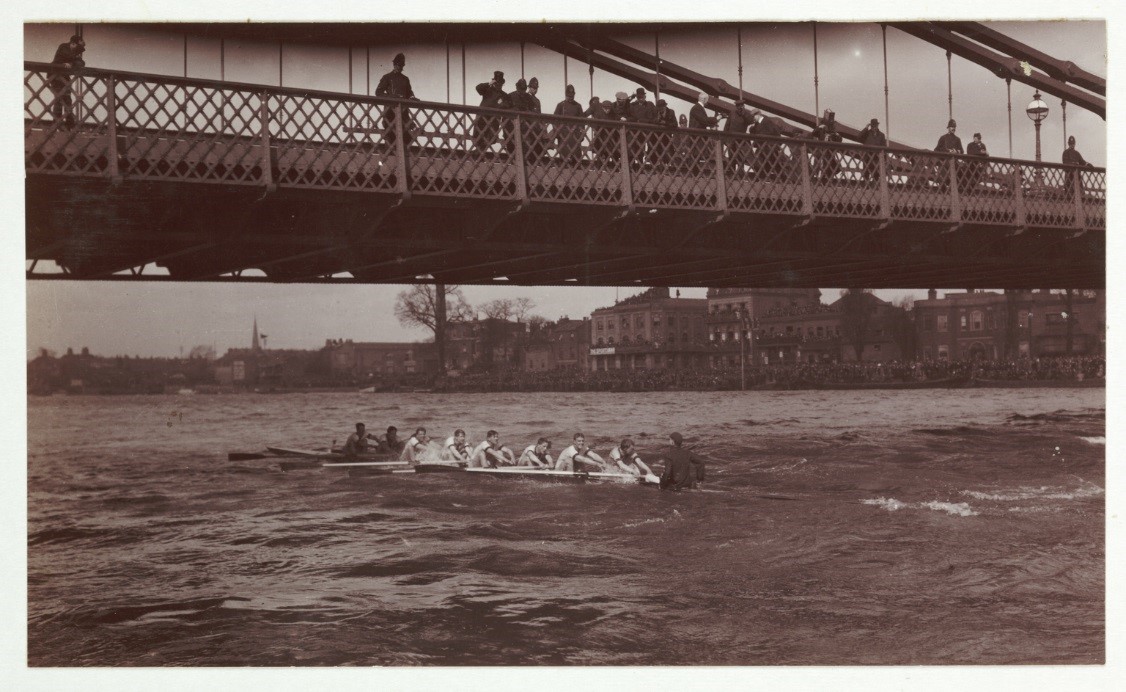

If you look at this snapshot of the Boat Race, look closely at the people on the bridge and the fifth person from the right (just along from the man clinging onto his bowler hat), he is clearly holding a cine camera (the shape is that of a classic English upright design of the time). This is probably a newsreel cameraman at work. Newsreels were one of the main ways in which the public kept in touch with world events and this was the way people could see the Boat Race (or any other sporting event) if they weren’t able to be there. Newsreels were at the forefront of rising to the challenge of getting news images to an audience as quickly as possible.

The historic (in television terms) 1938 Boat Race was also filmed by newsreel companies such as British Pathé, and in a very meta moment, a newspaper photographer photographed a film crew filming the Oxford boat crew (still with me?).

Here, in an image taken from an original glass negative in the Daily Herald Archive at the museum, the Oxford crew are shown examining a newsreel camera as part of some pre-race publicity.

And here you can see the British Pathé newsreel from that year:

But for even earlier moving footage of the Boat Race, we can go back as far as 1895. The Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race film can be considered the first British sports film. It was made by one of the earliest film-makers in the world, Birt Acres, who clearly saw both the dramatic and commercial potential in the subject.

On 30 March 1895, Acres set up the camera he had developed along with his producer, Robert Paul (sadly no longer in existence) at the end of the race to capture the crucial moments. It was of course a single, silent, black-and-white static shot with the camera in a fixed position which ran for about 1 minute (the whole race would have lasted for around 20 minutes) and is one of a handful of British films which can be dated to 1895.

Between 1829 and 2018 the Boat Race may have stayed the same, but film and broadcast technologies, speed and presentation styles have all changed dramatically to give audiences the best view of the race from their own homes.

Interested in the innovative technologies used to broadcast iconic sports? Come to the National Science and Media Museum this summer for our exhibition Action Replay, opening 13 July 2018.

Wonderful Boat Race, But I Would Be Happier If Cambridge Had Won !