As we prepared to reopen our museum and cinemas, we got to thinking about welcoming you all back to the screens and redressing our cinema spaces.

In 2019 we produced an exhibition called The Forgotten Showman, where we explored the life and work of Robert Paul, a pioneer of cinema in the UK. As part of the exhibition, we worked with artist ILYA and Professor Ian Christie, who had previously partnered to produce a graphic novel to tell the story of Robert Paul. Working with the design studio Instruct and ILYA, we commissioned new illustrations as part of the gallery design. Some of these were life-size versions of influential characters working with and at the same time as Robert Paul.

When we remove a temporary exhibition, we always think about how we can recycle and reuse the printed materials. We purposely print on recyclable material for things that can only be used once; most of the text panels from this exhibition have gone on to have a second life; and our collaborators and partners also take some of the material. In the past, partners and colleagues have even transformed used exhibition materials into kitchen cupboards!

When it came to these life-size figures, we decided they might approve of a new life in Cubby Broccoli Cinema. This gave us the opportunity to work again with ILYA and Instruct Studio to produce more cinema pioneers. We worked to decide on a total of six pioneers who we’ll explore further in this post. You can meet them all next time you visit our Cubby Broccoli screen at the National Science and Media Museum!

Alice Guy-Blaché

1873–1968

First up we have Guy-Blaché, who was probably the first woman film-maker and certainly among the first to direct a fiction film. She began as office manager with French cinema industrialist Leon Gaumont in 1895; she became directly involved with film-making the following year when she was put in charge of the Gaumont company’s film production, where she worked on around 1,000 films. In the early cinema landscape, actualities (or documentaries) were most common, but she was especially interested in using film to tell a story.

She moved from France to the USA and in 1901 founded her own studio, Solax, initially using the facilities of the Gaumont Studio in New York. She was so successful that in 1912 she had her own studio built in Fort Lee, New Jersey. She mostly made short films such as Cupid and the Comet (1911), A Fool and His Money (1912)—which had an all-African American cast—and Officer Henderson (1913). She continued to make films throughout the 1910s, but when she returned to France in the early 1920s she was unable to find work in the film industry and instead wrote children’s books. She faded from the public memory until, in 1953, the French government presented her with the Legion d’Honneur.

In 2018 a documentary about her life and work, Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, was released.

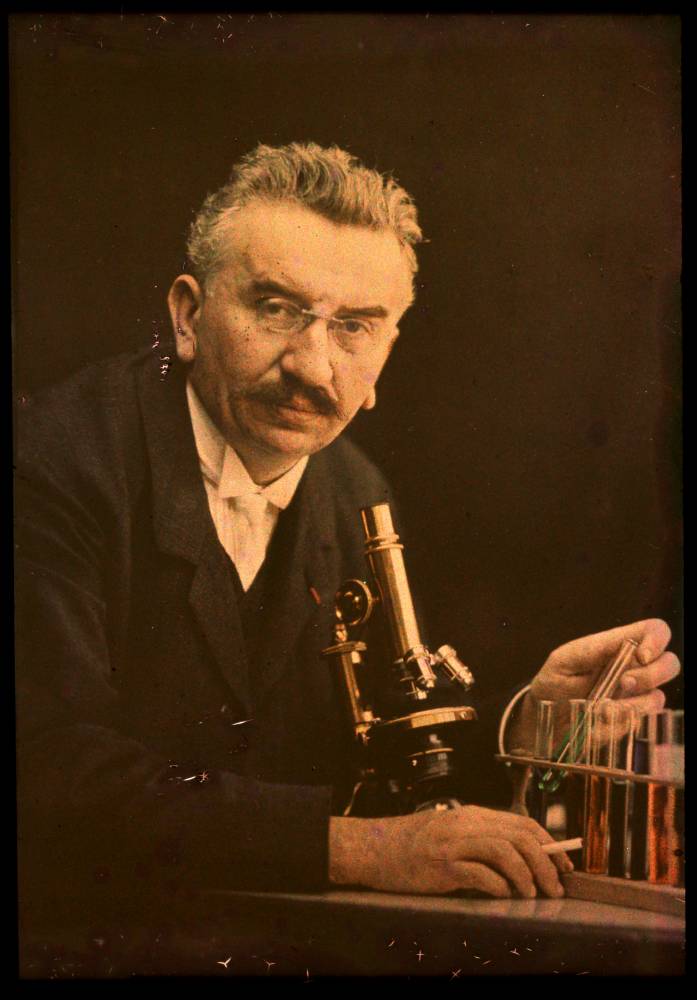

Louis Lumière

1864–1948

Along with his brother Auguste, Louis Lumière was pivotal in bringing both cinema and photography to the masses. From his teens, Louis worked at his father’s photographic factory, developing new products and contributing to the success of the family business. Inspired by Edison’s kinetoscope, the two brothers began working on a machine to record and project moving images. It was Louis’ suggestion of using a mechanism similar to a sewing machine that finally brought success. On 22 March 1895, the Lumières and their head mechanic gave a demonstration to the Société d’Encouragement pour l’Industrie Nationale (which, interestingly, Alice Guy-Blaché attended).

It was a presentation which helped to set the template for cinema. Louis oversaw the development and manufacture of the equipment and was the first Lumière camera operator, while Auguste arranged the commercial exhibition of it, which began in December 1895.

The Lumière brothers played an important role in The Forgotten Showman as they were working on their projectors simultaneously to Robert Paul, with both premiering in Leicester Square on the same day!

Louis Lumière continued his research into still and moving images and, among others, developed the autochrome process, released in 1907—one of the earliest colour photographic processes.

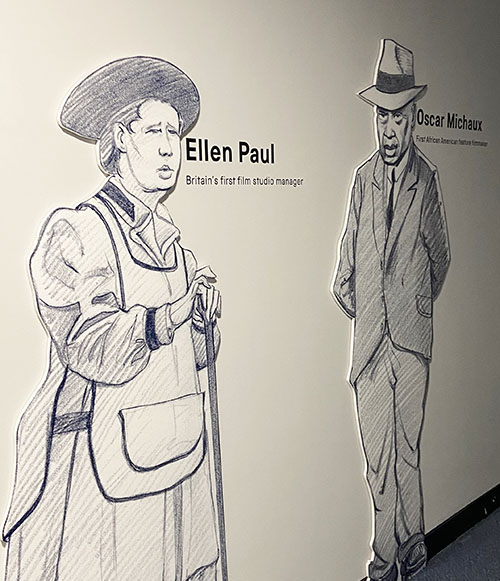

Oscar Micheaux

1884–1951

Early mainstream American cinema rarely offered representations of the lives of Black people, and many Black cinemagoers were forced to attend separate screenings from white patrons or restricted to second-run theatres. These circumstances led to Black theatre owners and Black performers teaming up to provide venues and talent for early Black film-makers. Several companies appeared during the early 20th century; one of the most successful was the Micheaux Book and Film Company, founded by Oscar Micheaux in 1918.

Oscar Micheaux was an author before he became a film-maker, writing seven novels. They included The Homesteader, based on his own experiences, which was to become the first film made by his company; sadly this film is now lost. He then went on to produce over 40 films between 1918 and 1948, including Within Our Gates (1920), the earliest surviving feature film by an African American director and a landmark in the history of American cinema.

Some critics believed the depictions of violence would incite riots—the film was released just one year after racist attacks in Chicago, and depicted similar scenes. Censors made many cuts to the film, meaning audiences in 1920 rarely saw it as Micheaux intended. However, one reporter agreed with Micheaux, writing that:

“… those who reasoned with the spectacle of last July in Chicago ever before them, declared the showing pre-eminently dangerous; while those who reasoned with the knowledge of existing conditions, the injustices of the times… determined that the time is ripe to bring the lesson to the front.”

His films depicted contemporary African American life, including the challenges for Black people when trying to achieve success in wider society. He commented:

“It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights.”

A documentary about his life and work, Oscar Micheaux: The Czar of Black Hollywood, was released in 2014.

Ellen Paul

1867–1954

The roles of many people in the earliest days of cinema are often hidden; frequently this can mean stories of women’s involvement are unacknowledged. One such example might be Ellen Paul, somewhat overshadowed by her husband’s success.

Ellen worked as a dancer at the Alhambra Theatre in London under her stage name Ellen Dawn (real name Ellen Daws). It was there that she met the engineer and newly established film mogul Robert Paul; she featured in his film The Soldier’s Courtship (1896), which was filmed on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre in 1896. She played the busybody interfering with the courting couple’s smooches.

There is no known photograph of Ellen, but as well as The Solder’s Courtship she can be seen playing the wife in Come Along, Do! (1898), tackling a burglar in His Brave Defender (1902) and falling into fits of laughter in Fun on the Clothesline (1986).

Film-making at this time did not have specific roles (such as director) assigned, but was more of a group activity to complete the necessary tasks. Alongside her onscreen performances, it has become clear that Ellen played a major role in running the film business, particularly launching and managing the UK’s first film studio complex built by Robert Paul in 1898: “his wife was producer, stage manager or principal lady in many a playlet for which her expert knowledge eminently fitted her.”

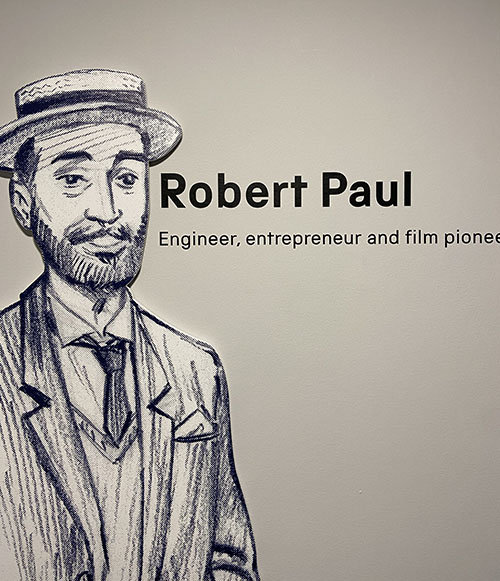

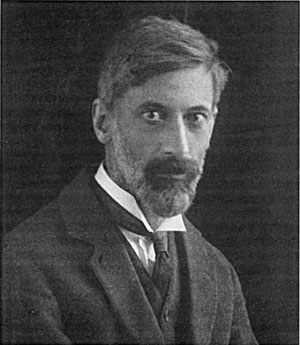

Robert Paul

1869–1943

Paul was one of the founders of the British film industry, who had a global impact on the development of cinema. To find out more, read our story Robert Paul and the race to invent cinema.

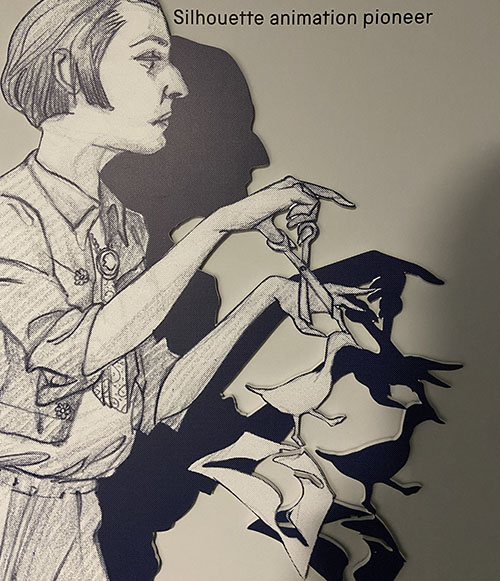

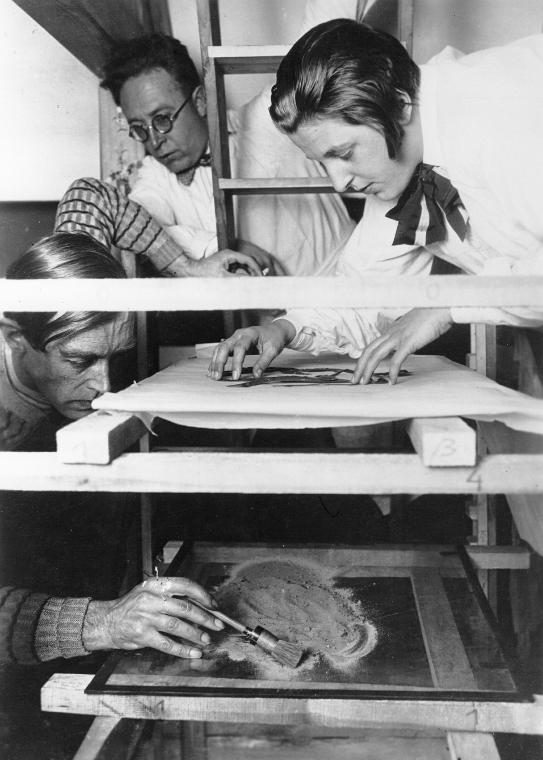

Lotte Reiniger

1899–1981

Lotte Reiniger is a pioneer of film animation, particularly silhouette films, in which paper and cardboard cut-out figures hinged at the joints were hand-manipulated from frame to frame, lit from below and shot via stop motion photography. Her characters were created and animated with incredible skill and precision. She created the earliest surviving animated feature film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), one of the milestones of cinema history.

She was attracted to timeless fairytales as inspiration for her animations; the short films Aschenputtel (Cinderella) and Dornröschen (The Sleeping Beauty), both from 1922, were among her earliest work. After completing Prince Achmed, Reiniger never again attempted a feature-length animated film; for the rest of her 60-year career she concentrated on shorts, and on sequences to be inserted in other people’s films.

Altogether, Reiniger made nearly 60 films, and around 40 of these survive. In December 1935 she moved to England from Germany and continued to work, making The King’s Breakfast (1936) and other films for the GPO Film Unit. After the war, Lotte and her husband and artistic collaborator Carl Koch took British citizenship and settled in London. After a period of not working, she returned to animation and made two more features before her death in 1981.

You can see the new display celebrating pioneering film-makers in the corridor leading to our Cubby Broccoli cinema screen on Level 1 of the museum. Our cinemas are currently open Wednesday to Sunday—the full film programme and tickets are available on our cinema pages.