I have a confession to make. I’ve just started working here and I don’t know half of what this museum contains. Less than half. Even less than that. But apparently, that’s okay, because according to curator Colin Harding it would be impossible for one person to know it all. If what’s on display in the museum is anything to go by, the rest is well worth investigating.

In an attempt to get an overview of the 3-million-plus objects that live here, I went on a tour around our Collections & Research Centre on my lunch break.

We began the tour by meeting Colin Harding, Curator of Photographic Technology, who explained to the group that the purpose of the tour is to give you access to the vast majority of objects in the collection that are not on permanent display. He calls this “iceberg syndrome”, as most visitors see only the very tip of the archive. It’s a problem all museums suffer from.

Colin stressed that the collection here belongs to everyone (“you don’t need a letter of introduction from your MP”), and that there is no charge to access the Insight rooms, but, because some of the objects are hundreds of years old, and fragile with it, there needs to be a balance between access and preservation.

The first room we visited was the Gandolfi room (named after the Gandolfi brothers who were making cameras in the early 20th century), used as a research area, where the helpful team will bring any materials that are requested by visitors and researchers. A second room named after the founder of the Focal Press, the Kraszna-Krausz room, can be used for group visits—it’s something of a personal exhibition space.

In the print archives, the team were preparing for the upcoming exhibition of Tom Wood’s photographs—mounting and framing images, and generally looking very busy. We were shown some examples of the very earliest photographs, daguerreotypes from the 1840s, and collodion positives from the 1850s and 1860s.

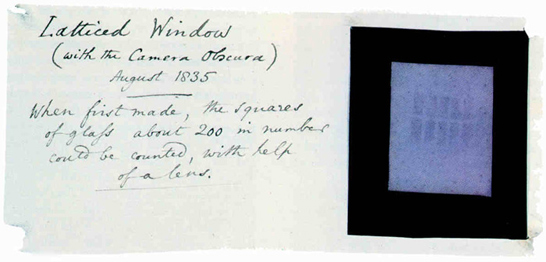

Colin talked us through the general archiving and storage process. The room is pretty chilly and dry, as these are the best conditions in which to preserve these precious items, and we learn that somewhere in this room is the world’s oldest surviving negative: Henry Fox Talbot’s latticed window (1835), which Colin has seen only twice during the last 25 years because it’s too fragile to be exposed.

We move on to talk about the libraries and archives we look after. They house objects which demonstrate the history and development of the still and moving image that even the British Library doesn’t contain.

The large and small object stores are a real treat to visit. Items include the (oh so glorious) Technicolor Camera, a Mellotron sound effects machine (like the one used on the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album) a machine gun camera used for military target practice (much safer than using a real gun, especially with my aim), and examples of every Kodak camera ever made, bar one: The Cone.

I even had a rush of nostalgia looking at the old Polaroid cameras and Game Boys, but I won’t tell you which ones because that might give away my age! With so many rare, unique and significant objects, I feel like it’s a real privilege to work where they live.

Our last stop is the Daily Herald archive, preserving not only the images but the storage systems, even down to the box files, used until the newspaper’s closure in 1969.

It was fascinating to see how photographs were stored at newspapers before everything was digitised, including the gruesome-sounding ‘Morgue’ section where staff needed to look if the person had died. The archive gives real insight into the world of print journalism in the 20th century.

And so our tour concluded, but not without a final thought from Colin:

It’s not our collection, it’s yours. We just look after it on your behalf, and on behalf of future generations.

I love all this old stuff and have quite a large collection myself

http://www.flickr.com/photos/56036250@N03/