With Oscar fever running high and BAFTA results still ringing in people’s ears, it seems that all anyone can talk about is who will win what and take home the coveted gongs for this year’s awards season. But, with all this hubbub and with UK cinemas awash with award contenders like Les Misérables, Zero Dark Thirty and Django Unchained, it is easy to forget about the range and diversity of films released in this period and those that get swept under the rug by award-savvy distributors and cinema-goers alike.

This is a fact that ‘What is Cinema Now?’, a series of weekly discussions recently held at the museum, attempted to remedy.

Led by course leader Roy Stafford, the discussions focus on the range and breadth of films released throughout the year, in terms of country of origin, genre and classification (mainstream or specialised), as well as the considerations that distributors and film programmers have when choosing which films to exhibit, at what time, and where, a fact that Stafford argues is often overlooked in traditional film studies.

This time of year in particular is significant. While the holiday seasons are the perfect time to showcase spectacle and family oriented cinema (with the success of recent films The Dark Knight Rises and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey showing how well this formula works), January and February is the perfect time to capitalise on the buzz of awards ceremonies and showcase their ‘prestige pictures’—films with more mature and earnest content, such as Steven Spielberg’s historical drama Lincoln, which will often be nominated for one or several awards.

In terms of mainstream releases, the majority of prestige pictures are distributed via Hollywood companies such as Universal, 20th Century Fox, or Disney, whose size, networks and power can almost guarantee a worldwide release (in virtually all film territories) of the films that they distribute. In the UK, these films are awarded what is known as a ‘saturation release’ with digital and (less commonly) 35mm prints being sent out to cinema chains throughout the country (both multiplexes and smaller cinemas such as our own) totalling as many as 500 cinema screens at one time.

At the other end of the market is what are known as ‘specialised cinema’. Once referred to as the arthouse sector, specialised films are made outside the dominant studio system, such as foreign language titles and, in an increasingly common trend, UK, US and Australian films which are financed and distributed independently.

Unlike mainstream titles, specialised films are subject to limited release via smaller distribution companies like Artificial Eye or Optimum and are often only released in a handful of smaller specialised cinemas around the country—sometimes only in major cities like London or Edinburgh.

With no saturation release, specialised distributors often promote the artistic nature of a film using critical opinion, word of mouth and their reputation on the festival circuit in order to spread interest to an audience. For instance, the promotion of Michael Haneke’s Amour focused on its success at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won the coveted Palme d’Or, and used its critical reputation to steadily build momentum from a release in 20 cinemas to 40 the following week.

This method of distribution is not always black and white. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Amélie (2000) are two good examples of specialised films that enjoyed mainstream success, the former being a martial arts film, the latter a romantic comedy. Amour has enjoyed a crossover of its own, having being nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture (a category usually reserved for English language and mainstream titles).

With these complications in mind, the course questions the categories which determine film distribution, and in the first part of the series, asks what characteristics determine such categorisation, using recent release What Richard Did.

Directed by Lenny Abrahamson, the film is an independent Irish drama about a privileged and popular teenager whose life is shattered in a brief moment of violence. The fact that it was shown in only nine UK cinemas on the day of its release suggests that What Richard Did is part of the ‘speciality film’ set, but is its content deserving of that category?

What Richard Did has elements of kitchen sink realism, and a stripped-down approach to shot structure and sound design. It doesn’t attempt to manipulate the emotions of its audience, and instead distances the viewer from the characters on screen, offering room for interpretation (a fact underscored by its inconclusive and enigmatic ending). Each of these elements suggests that What Richard Did should most appropriately be categorised as a specialised film.

However, there are also elements that hint at a yearning for wider appreciation. The casting of Danish actor Lars Mikkelsen (the film’s most recognisable actor) as Richard’s father can be read as an attempt to appeal to a wider demographic. It evokes parallels with recent Scandinavian dramas such as The Killing and Borgen—indeed, these dramas themselves showcase the crossover capacity of specialised releases.

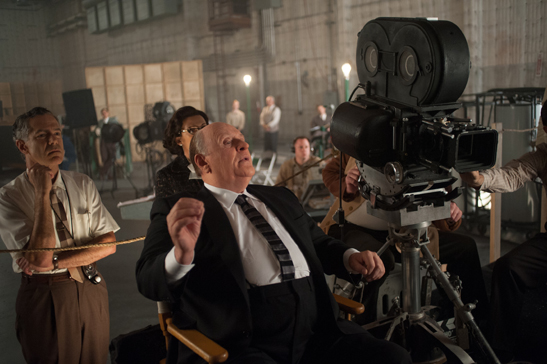

Conversely, Hollywood is known for borrowing styles, themes and techniques from specialised film, and this week’s discussion will focus on Hitchcock, and the parallels that can be drawn between mainstream and specialised cinema. Later on in the course, we’ll be considering the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, and the role that form and genre plays in film distribution.

One comment on “What is cinema now?”