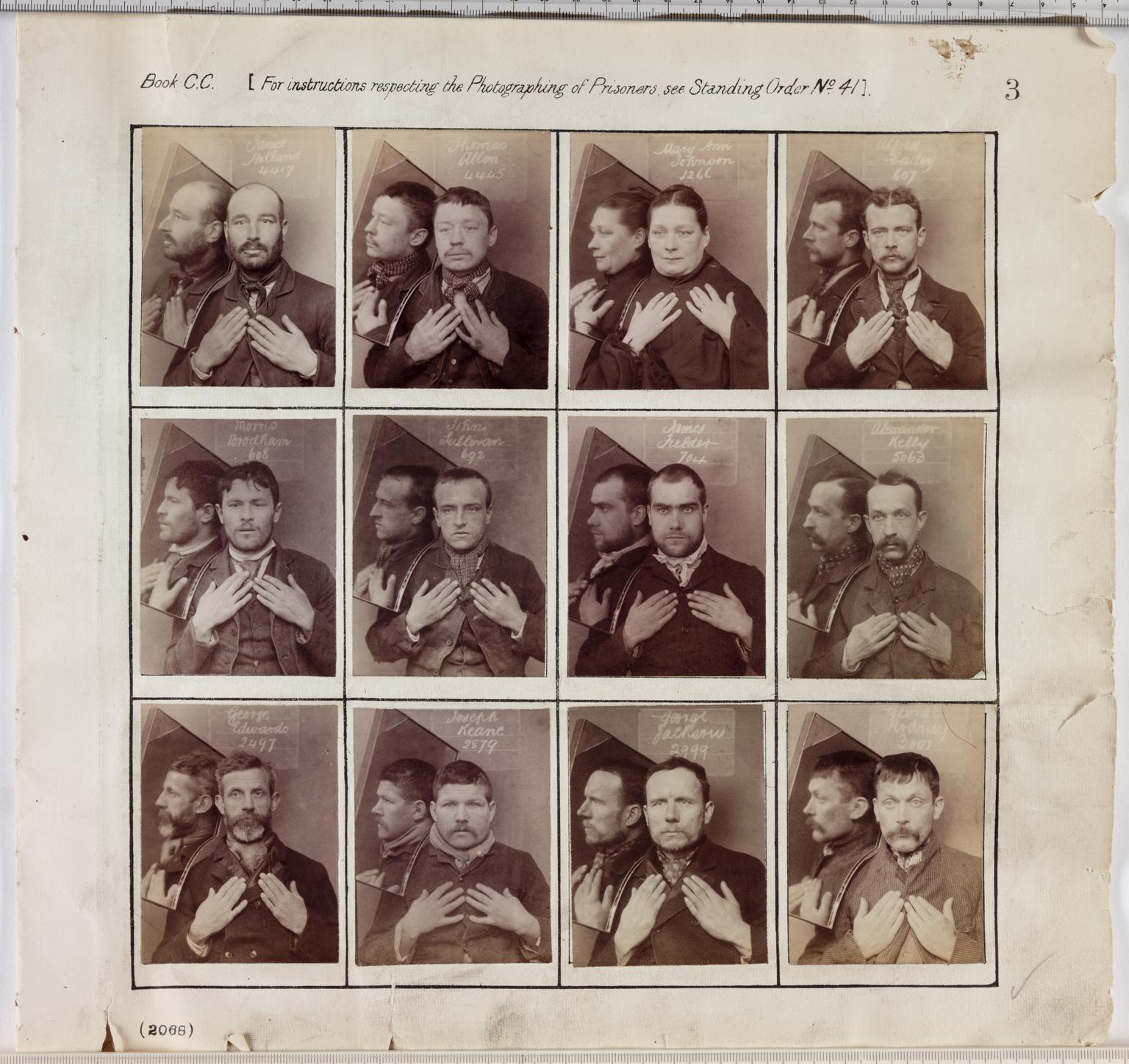

First proposed in 1879, Alphonse Bertillon’s identification system suggested criminals should have various body parts measured, then documented into a classification system. This was not merely a way of identifying them: it was also used as ‘evidence for the theory that undesired physical and mental characteristics were inherited’. The idea echoes the earlier philosophy of Cesare Lombroso, whose 1876 book Criminal Man argued that certain physical characteristics, including skin colour, facial features and tattoos, were indicative of criminality.

One might assume that today, these 19th-century ideas would be rightly dismissed as racist, sexist and classist. Yet echoes of such beliefs persist: as the Guardian reported in 2017, black people are eight times more likely to be targeted by police ‘stop and search’ procedures than white people. The idea that criminality is more prevalent in particular social, ethnic or cultural groups has also affected how surveillance technology is used.

In 2016, online retailer We Sell Electrical used data from a Big Brother Watch report, ‘Are They Still Watching? The cost of CCTV in an era of cuts’, to create an illuminating infographic. The image, a map showing the number of CCTV cameras in various UK cities, reveals the city of Brighton has just 84 CCTV cameras, while the London Borough of Hackney is home to a staggering 2,900. This is despite the fact that both have similar numbers of residents—in fact, Brighton’s population is slightly larger.

Why the disparity? The answer may lie in the demography of the two areas. In the 2011 UK census, 80.5% of Brighton residents identified as ‘white British’, with the non-white population amounting to just 12.2%. In contrast, only 36.2% of Hackney residents described themselves as ‘white British’. The Hackney area has long been associated with ethnic diversity: a profile compiled by Hackney Council explains that ‘labour shortages in the reviving post-war economy drew in migrants from the Caribbean, Cyprus, Turkey and South Asia’.

There is also an economic divide, with poverty, unemployment and welfare dependency more prevalent in Hackney. The Hackney Council profile goes on to state that Hackney was ‘the eleventh most deprived local authority overall in England in the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation’. In the same index, meanwhile, Brighton and Hove was in 102nd place.

Using the above evidence, we could potentially argue that areas with greater ethnic diversity and higher socioeconomic deprivation are subject to greater surveillance. Whether this is the case or not, it gives us another sociological angle from which to approach the topics covered in Never Alone. People from particular social or ethnic groups may feel more surveilled than others; stereotypes and prejudices can be just as apparent through a camera lens as they are through the naked eye.

One effect of this perceived surveillance is the development of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Initially developed by sociologist Robert Merton, this concept refers to the way certain social groups may internalise the stereotypes placed upon them and, in doing so, actually fulfil them. If a group is placed under greater surveillance and stereotyped as criminal, a self-fulfilling prophecy might mean that some individuals from the group may then go on to conform to those stereotypes. After all, the label has already been placed on them. This phenomenon is closely related to stereotype threat, which social psychologists Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson defined as ‘being at risk of confirming, as self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one’s group’.

This ties in with another sociological concept: the Hawthorne effect. Also known as the observer effect, this occurs when people change their behaviour when they know they are being observed. A classic example is someone working harder or more efficiently when their boss is watching. The Hawthorne effect can affect the validity of social research: if individuals modify their behaviour when being observed, we may not receive accurate or representative results.

With mass surveillance, however, people may feel they are always being watched—truly ‘never alone’. This has in fact been used as an argument in favour of mass surveillance. If would-be criminals know they are being caught on camera, they are more likely to experience the Hawthorne effect, modify their behaviour, and ultimately be deterred from committing crime.

But, in keeping with the questioning approach Never Alone takes to its subject matter, the visitor is encouraged to make up their own mind. In exchange for (arguably) greater security, are you willing to be constantly observed and recorded? While mass surveillance can certainly act as a deterrent, a camera is powerless against the deeper social and economic causes of crime. Ultimately, CCTV can provide a measure of safety, but no amount of surveillance can guarantee a crime-free utopia.

Never Alone is open at the National Science and Media Museum until 10 February 2019.

Excellent exploration of the correlation between areas of ethnic diversity/high socio-economic deprivation and surveillance. Thought provoking!

Another excellent instalment, well researched and written, also easy to understand by all age groups

Well done that man – another thought provoking piece. Interesting exploration of the correlation between areas of high levels of socio-economic disadvantage and high levels of surveillance.

Part 2 of this blog is equally insightful and keeps you gripped. A really clever piece. Looking forward to part 3!