This summer saw the highly anticipated Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer released in cinemas across the country to rave reviews. Nolan has said that 70mm print film is the best way to watch the film, either in IMAX 70mm—at three cinemas in the UK—or classic 70mm, which you can see at six UK cinemas including our own Pictureville Cinema.

But why is it so rare to see print films? Why is 70mm so special? And if this is the best way to watch it, why isn’t it more common?

Some common film formats and terms

You may often see film screenings at Pictureville or other cinemas mentioning things like ‘35mm’, ‘16mm’ or ‘8mm’, and to understand 70mm it’s worth a quick look at its close neighbours in film exhibition.

The primary characteristic used to categorise film is the ‘gauge’. Film gauge is the width of the physical film strip, as measured in millimetres. This width can determine the quality of the film itself; how much light passes through it during filming and projection, and the literal size of the film strip.

‘Perforations’, also known as perfs or sprocket holes, are the holes running down either side of the film strip, and they allow the film to be pulled through a camera or a projector. The number of perforations sometimes serves as an indicator for the ‘height’ of the frame.

- 8mm – First produced during the 1920s and created for amateur filmmakers to easily pick up and use. As a lower quality film gauge, it tends to produce a very soft image.

- 16mm – While also targeted towards amateur filmmakers from the 1920s onwards, it was used for lower-budget productions, ranging from educational films, advertisements and television programmes. It’s still very popular today, and Wes Anderson used 16mm film for Moonrise Kingdom (2012).

- 35mm – The majority of films shot in the 20th century were made on 35mm film stock, and it’s the standard for film stock. It established the 1.37:1 ‘Academy’ aspect ratio, which is the native ratio of standard 35mm film gauges. Innovations and variations in squeezing and cropping larger images produced formats like Cinemascope and Panavision, which meant images could be wider on screen but still filmed on 35mm film stock.

What is 70mm and why is it special?

While most film studios in the 1950s and 1960s were playing around with 35mm, a few select companies were working with 65mm film—better known as 70mm because you add another 5mm on for the sound in post-production.

Because it’s twice as large as 35mm, films in 70mm would often be in very wide formats and because you’re shooting on larger negatives you get a bigger, brighter, and more detailed and vivid picture.

In modern terms (though not entirely accurate), 35mm film is equivalent to a 5 or 6K digital resolution. 70mm film is closer to 16 or 18K, so when you’re watching 70mm film, it has visual fidelity far beyond that of any digital cameras we use today.

IMAX 70mm is even bigger because film runs through the camera and projector horizontally, so each frame uses 15 perforations of the film compared to the vertical 5 perforations of regular 70mm. This makes the frames 3.4 times bigger than on ‘standard’ 70mm film.

Where did 70mm film come from?

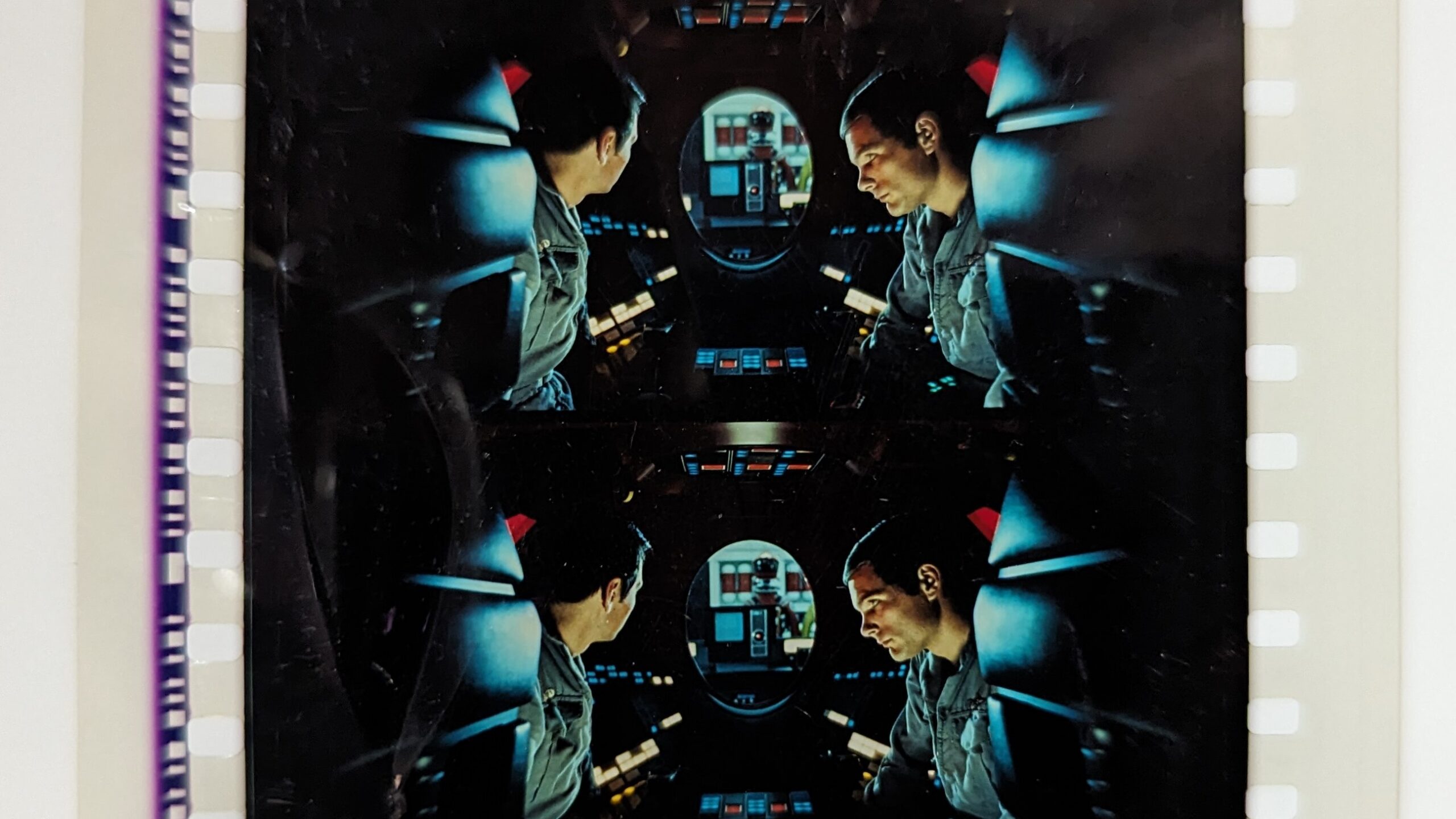

Even though the 70mm era is characterized by films like Oklahoma! (1955), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the format is much older than you’d think. It was either invented between 1894 and 1897 by Herman Casler or, alternatively, by William Fox and Theodore Case with their ‘70mm Grandeur’ film from 1928. The more popular theory is the latter but either way, use of the format was not popularised until much later due to the cost of production.

When the film industry eventually had to compete against television, Cinerama was the first of several immersive processes introduced during the ‘widescreen war’ of the 1950s. It utilised three 35mm projectors playing side by side, resulting in an incredibly wide image for a curved screen. Due to the impracticalities of Cinerama, co-founder Michael Todd would go to work creating a new film format that could combine the size of three 35mm projections into one large film format. 70mm was back!

Why are screenings so rare?

70mm is expensive, and it always has been. One single finished 70mm print can costs around £50,000 per copy to produce today.

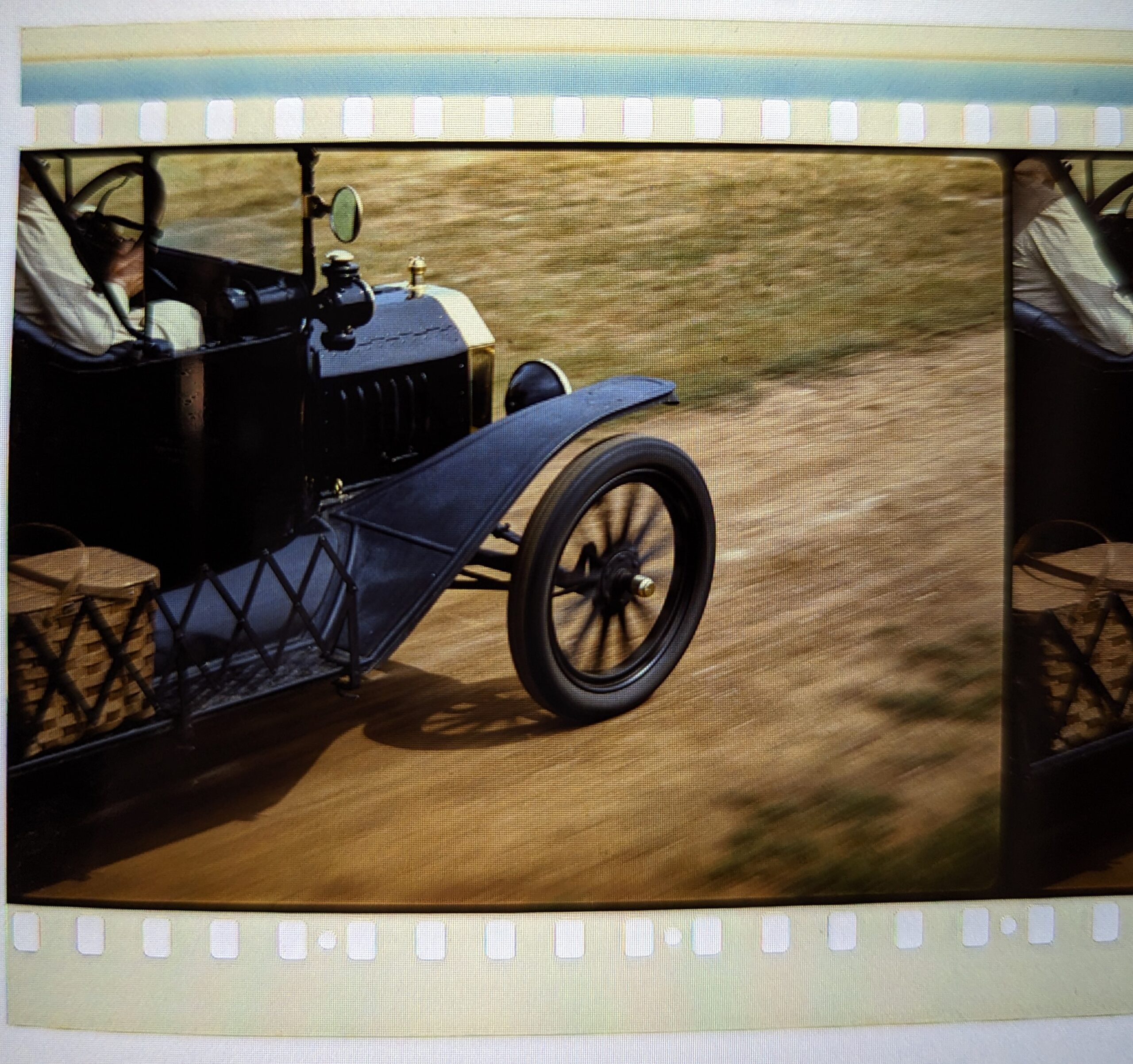

And because of these costs many popular 70mm films would have had ‘roadshow’ releases, where a small number of prints would tour around with all the pomp and circumstance of a theatre production or recording artist, before a wider release on cheaper 35mm film.

70mm is also a very specialist format, and currently only six cinemas in the UK have the equipment needed to screen films on 70mm. Most cinemas removed their analogue projectors when digital came to dominate the industry, and before that the industry standard was 35mm film in all cinemas, meaning that projectionists who knew how to project 70mm were already very rare.

70mm film is also difficult to maintain, as prints deteriorate and fade, and to transport and store due to their size—Oppenheimer 70mm prints have been stated to be nearly 300kgs and 18km long.

Is it really worth it?

In a word, yes. And we’re not even biased.

There’s a reason why filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Paul Thomas Anderson and Kenneth Branagh keep the format alive despite the costs. And why there are cinemas that have kept their equipment to screen it, and even why there are festivals each year that celebrate it.

70mm is a must-see experience for film fans. It’s the quality that digital has been working towards and there’s a whole industry of movie-effects makers that have been trying to recreate its unique look.

We noted that most film from the 20th century was shot on 35mm, so imagine if any film you’d ever seen had double the amount of detail, double the colour and depth, double pretty much everything on screen. Many would compare it to the difference between digital and vinyl music formats, but it’s more like digital versus a live acoustic performance—unmistakable quality without any digital compression between you and the frame.

However, the best way to judge really is to see it for yourself and you’ll get the chance when Oppenheimer comes to Pictureville from 11–17 August 2023.

Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I am looking forward to seeing Oppenheimer this week.

For a science-based outfit, you make a most amusingly basic mathematical error throughout your article which calls into question the integrity of the whole thing. 70mm film negatives are NOT, as you state, “twice as large as 35mm”: they are FOUR times the exposed area of 35mm film stock, not just double the the width but double the height as well. Have you ever even seen a single frame of 70mm stock? I actually have some of the removed footage from the original Roadshow release of “2001”: and it’s gigantic compared to 35mm. Do your homework properly.