For the next post in my A-Z of photography in our collection, I want to share with you one of our greatest treasures. Taken in 1843, the Hogg daguerreotype is the earliest known photograph of a photographer at work.

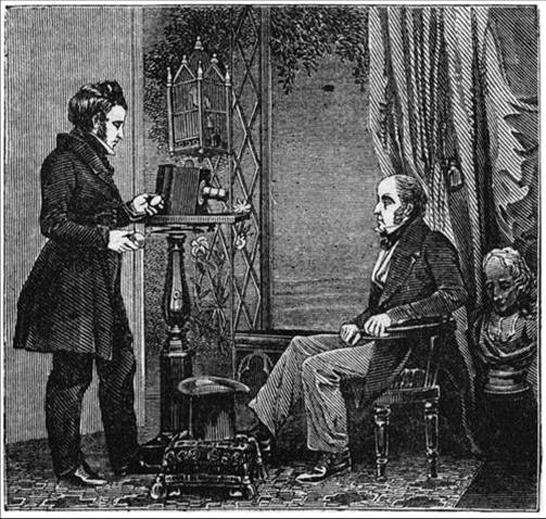

The daguerreotype shows Jabez Hogg, in the act of taking a photograph. Jabez Hogg (1817–1899) was a man of many talents—surgeon, microscopist, journalist and photographer.

In 1840 he entered the medical profession as an apprentice to another photographic pioneer, Dr. Hugh Welch Diamond. He was an active collaborator in Diamond’s photographic experiments and in 1843 wrote one of the first photographic instruction books, A Practical Manual of Photography, in which a woodcut reproduction of this daguerreotype was used as an illustration.

Also in 1843, Hogg joined the staff of the Illustrated London News and the same woodcut subsequently appeared in this magazine, accompanying a poem entitled Lines Written on Seeing a Daguerreotype Portrait of a Lady.

The caption tells us that the daguerreotype was taken at ‘Mr. Beard’s establishment, Parliament Street, Westminster’.

Richard Beard, a former coal merchant, had opened Britain’s first photographic portrait studio in London’s Regent Street in March 1841. The following year he opened two further London studios, one at 85 King William Street and the other at 34 Parliament Street.

According to a manuscript note on the back of the daguerreotype, the sitter is a ‘Mr. Johnson’. He is probably an American, William S. Johnson, the father of John Johnson who came to Britain in 1840 to assist Beard with some of the technical aspects of setting up his studio.

In the daguerreotype, Jabez Hogg can be seen timing the exposure with his pocket watch, having removed the lens cap which he holds in his other hand. Johnson Senior poses stiffly in an armchair, his hands tightly clenched as he tries not to move during the exposure which could last up to one minute.

In 1977 this daguerreotype was sold at auction to a German private collector for what was then a world record price for a single photograph of £5,800.

In 1983 it was bought by this museum, or rather the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, as we were then known. It is now on permanent display—come and see it in our Kodak Gallery.

Further reading and interesting links

- A short biography of Jabez Hogg with references for some obituaries

- Jabez Hogg, A Practical Manual of Photography, London: E. Mackenzie, Cleave, Clark, 1845

- Stuart Bennett, ‘Jabez Hogg Daguerreotype’, History of Photography Vol 1, No 4 (October 1977) p. 318

- ‘Jabez Hogg and Mr. Johnson’, The Photographic Collector Vol 4, No 1 (Spring 1983), pp. 8–9

Reason would indicate any daguerreotype taken 1843 would be in the public domain by 2014, even in those unfortunate countries suffering under the yoke of the longest possible copyright terms. Yet I can find no acknowledgement that this is the case here. Creative Commons has a Public Domain mark that you can use to help people know creative works are in the public domain.

While you include buttons that allow sharing your blog post in a wide variety of places (one such share is what brought me here) there is no indication that your blog is licensed to share.

If your intent is to allow people to share, you should really consider indicating what is actually allowed by using the appropriate license; for cultural works I always recommend Creative Commons, as their licences are the most widely known and understood. If sharing is to be limited of the limited nature provided by the share buttons, you should attach a “Copyright All Rights Reserved” notice to the blog, so people understand that copyright applies.

Before I reblog anything in my Tumblog, I need to make sure it carries a free culture license, so I can’t share this there at this time.

I note that you have provided a wordpress share button as well; the problem is that but that only facilitates sharing on my main wordpress.com blog; what if I would rather post it on one of my self hosted wordpress instances?

These buttons allow sharing in only the most limited way, by restricting sharing this image to posting a link back to your blog for the image source. Although I link and attribute any image (including public domain works) posted in my blogs, I have learned links can be unreliable, so the only way to ensure the content of my blogs does not vanish when a link to the source is broken for any of a variety of reasons, the safest course is to host the actual content in my own blog’s image files.

I hope this has been of some help.

Hi Laurel

Thanks so much for your comments. Since this post was written, we have now started to release digital images for which we own copyright under the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license. You’ll notice this change on our more recent posts.

I will also add a note to our about page to clarify how people are able to use our written content. In the meantime, I’m happy for you to re-blog the content of this post as we own the rights to these digital images, but please credit © National Media Museum, Bradford / SSPL. Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

Best wishes,

Emma

Dear Emma:

It is an excellent idea to make your policy on sharing clear. The National Media Library certainly has the right to dictate such terms for the creative works to which it holds the copyright.

But public domain works like the 1843 Hogg daguerreotype pictured here are quite a different story. Because although the National Media Museum owns the physical work, it is NOT the copyright holder. The public is the copyright holder of works in the public domain.

The Louvre owns the physical painting known as the Mona Lisa. Yet copyright law has allowed people to legally copy her for centuries. MIT has digitised the works of Shakespeare. Does that make MIT the copyright holder of the works of Shakespeare?

The National Media Museum is within its rights to keep its public domain holdings locked away out of the public view under property law . But once public domain works are displayed to the public, whether on or off line, they are fair game. People are allowed to make copies, with pencil and paper or camera, because the use of public domain works is not restricted by copyright law.

You should also be aware that the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license is not considered a “free culture” license. I’ve heard it called the “advertising license” because the only benefit it confers to the public is the ability to advertise.

Copies of pictures in books or online are no substitute for the real thing. When people visit museums and galleries they want to see the originals. This is why Art Galleries don’t display perfect forgeries of famous paintings, they must have the real thing. The first artist who painted a mustache on The Mona Lisa didn’t detract from her fame, he just made her more famous. (And ensured more of the public would make a pilgrimage to the Louvre.)

Free culture licenses benefit all because they facilitate the spread of culture. And as copyright law becomes more repressive to culture, such licensing becomes far more important.

Regards,

Laurel L. Russwurm

so…as it turns out Jabez was my Great Great Grandfather…personally I am vry happy to see anything about Jabez!

Jabez was my Late step father’s great great grandfather too . He was Anthony Dollard , grandson of Ada Hogg and Dr Richard Dollard. Would be great to be in touch to find out more about the connection.

Kind regards

Robert Amis

so…as it turns out Jabez was my Great Great Grandfather…personally I am vry happy to see anything about Jabez!

I notice you cite Hogg’s 1845 edition of his manual, yet you claim it was reproduced in the 1843 edition. Have you seen the 1843 version. I can’t find any evidence of it existing and wonder if this isn’t a little myth.