Streaming and on-demand services provide audiences access to thousands of new and historic television programmes at the click of a button. Netflix has been building its own back catalogue, while new streamers Disney+ and BritBox rely on the rich archives of their founders.

Film creates a permanent record—but at its creation television was conceived to transmit live pictures, so how did we end up with such a legacy of something so ephemeral?

Mechanical recording

In 1927, only a year after John Logie Baird made his first television demonstration, he successfully recorded images to disc. Linking his spinning wheel televisor to a record cutter, he preserved the electric vision signal as a sound signal onto a shellac disc.

Phonovision was an experiment and only six recordings survive of this early milestone. It would be almost 60 years before the blurry images were recovered via computer processing to give a glimpse of what early viewers saw.

Chemical recording

Before it was interrupted by the Second World War, the BBC had launched a new television service with higher quality pictures that brought large-scale productions to living rooms of those privileged enough to afford the expensive new technology. Broadcast from studios at Alexandra Palace, none of those early programmes survive.

Without recording, repeating popular programmes required the entire production to performed again. Programmes could be made on film and then broadcast through a process called telecine, but filming a television screen would create a distorted picture with the image out of sync with the film.

In 1947, the year after the television service resumed, the BBC successfully captured live television images to film using a process called telerecording. The first programme recorded was Variety in Sepia on 7 October 1947. The variety programme celebrated Black talent and included notable performers including Evelyn Dove, Winifred Atwell and Edric Connor; the only surviving fragment is a performance of ‘Chi-Baba, Chi-Baba (My Bambino Go to Sleep)’ by Adelaide Hall.

Video credit: BBC

Prestigious television broadcast recording followed for the Cenotaph ceremony and the wedding of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Philip in November 1947. The technology was not perfect; during a recording of The Quatermass Experiment in 1953, an insect that landed on the screen was inadvertently permanently recorded into the footage.

In many ways television’s crowning moment, the Queen’s Coronation in 1953 saw television viewers outnumber radio listeners for the first time. The Eurovision network took the broadcast across Europe, but without satellite technology the television signal could not yet reach across the Atlantic.

To capture the historic broadcast, telerecording facilities at Alexandra Palace recorded hours of footage. The film reels were then loaded onto a helicopter from the grounds and taken to Heathrow, where the Royal Canadian Air Force were waiting with a specially fitted plane to develop the reels en route to Canada. Ready for broadcast by landing, the footage was retransmitted on the same calendar day across North America.

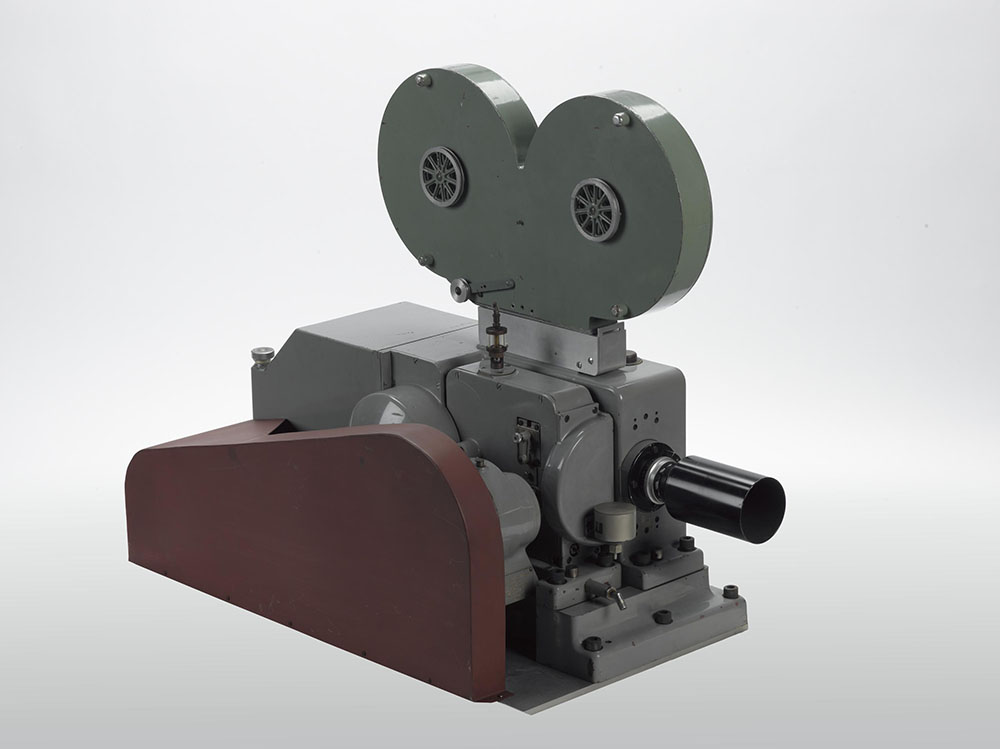

Magnetic recording

Recording to film was expensive, so from 1952 Peter Axon at the BBC began experimenting with recording television to magnetic tape, which was already used for recording sound. VERA (Vision Electronic Recording Apparatus) was demonstrated on air by Richard Dimbleby on Panorama on 14 April 1958. The new system did not just record television; it allowed the footage to be rewound and instantly replayed in the same show.

‘This is now me again… really’—Richard Dimbleby after demonstrating tape recording on air

VERA was a huge leap in recording, but the large tapes ran at very high speed, allowing only 15 minutes of recording each. The American system Ampex introduced later that year had a longer recording time. Television could now be regularly recorded as it went out, and developments also allowed productions to be recorded ahead of time for broadcast, a technique used for many famous British sitcoms including Dad’s Army and Fawlty Towers.

An advantage of tape over film was that it could be reused. Many early programmes recorded by the BBC were subsequently wiped and lost when the tapes were put back into use to save costs. When domestic video tape recorders were introduced in the late 1970s, the situation changed. Old programmes could be issued on video for sale and viewers could record their favourite programmes direct.

The popular television personality Bob Monkhouse was an enthusiastic home recorder. His off-air recording preserved hundreds of television programmes that reflected his interests in comedy and light entertainment. Always encouraging of new talent, it was only after his death that the only copy of Lenny Henry’s first television appearance on New Faces was rediscovered.

Digital recording

Developments in digital recording allowed much more information to be recorded to tape. Predating the arrival of digital terrestrial television, Sony launched their D1 in 1986, and the BBC adopted the D3 system to preserve their television archive from 1991. The BBC amassed around 350,000 D3 tapes before the technology became obsolete.

With so much historic footage locked on older format, the BBC launched the Digital Media Initiative to digitise its archive and allow tapeless workflows so staff could find and edit footage from servers. The project collapsed, but domestic viewers have happily shifted from tape to server storage.

With the shift to digital television, early video recorders have been replaced by smart boxes. The early system TiVo was an independent box that allowed television recording without tapes. It was quickly superseded by all-encompassing smart boxes that provide multiple services. Sky+, introduced in 2001, allowed viewers access to satellite television and recording of shows.

Catch-up services like the BBC’s iPlayer, launched in 2007, have seen many viewers abandon recording altogether. However, the demand for increasing amounts of content from streaming services has made the need for television producers to record and preserve television even greater. Thanks to recording, we now have access to thousands of hours of television at the click of a button.

I saw the grave and portly Dimbleby’s demo of VERA. I was 10, viewing a bakelite Bush with water-filled magnifier on it’s 9″ screen. The VERA thing was the size of an upright piano – taller. I later heard that – due to no helical scan – the tape ran past the heads at an almighty rate. The technicians would occasionally be terrified; pursued round the room by a berserk in the form of a tape-reel having coming off the spindle at high RPM. Ah, those were the days. Ferrographs too, rewinding at dangerous speeds, taking off the odd incautious finger-nail. True and proper machinery for the age.

This is wonderful! It gives me SLIGHT hope that perhaps ‘Cookery’ with Philip Harben broadcast 24/10/1947 was recorded…? My grandfather appeared giving butchery advice. I never met him, would love to find the footage. Details: http://doinkydoodles.blogspot.com/2014/05/finding-my-grandad.html

Many thanks. Luke

Why is there nothing about shooting in digital format?