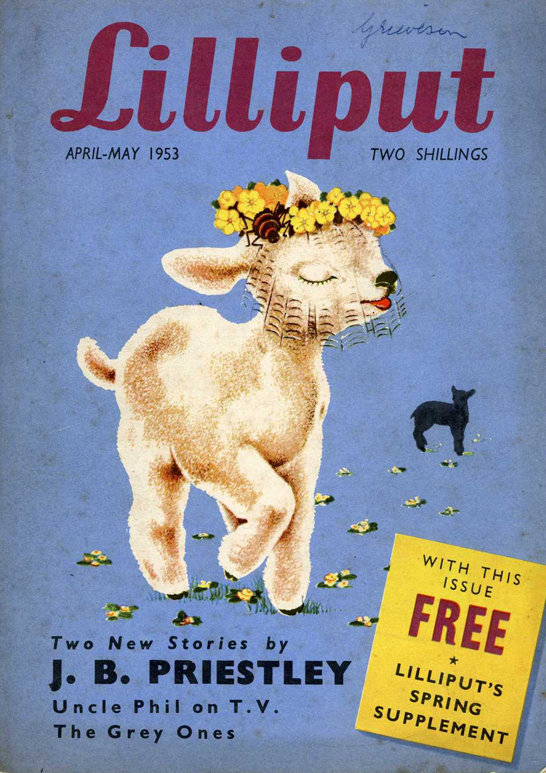

‘Uncle Phil on TV’, a short story by J.B. Priestley (1894–1984), was published in 1953—just two months before the Queen’s Coronation, the live event that would put television on the map in Britain. In fact, the Bradford-born author and broadcaster’s contributions to television were many and varied.

His fascinating tale would have been spooky reading in 1953, when television was still very much a novelty.

The cultural context

Television had been around for years, but take-up in Britain (in comparison to America) was slow due primarily to the impacts of the war, and the time required to build new transmitters. The majority of people in Britain had still never seen a television set, and the Queen’s coronation—which so famously spurred many British households to invest in their first TV—was still a couple of months away.

‘Uncle Phil on TV’

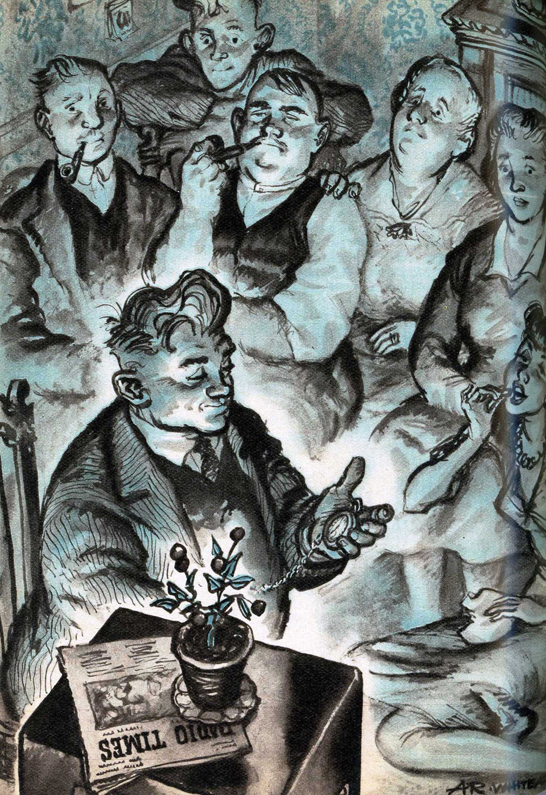

In ‘Uncle Phil on TV’, it slowly dawns on the Grigson family that their newly purchased television has become a vessel for the transmigration of their recently deceased relative’s soul.

Metaphorically, the mixed feelings of the time about the arrival of television are taken to the extreme and made more explicit for the reader. Priestley initially takes the opportunity to show television in a positive light—introducing several formats, such as the game show, the variety show, and the talk show—until, ominously, various family members keep spotting a distinctive figure in the background:

He carried his head to one side. He had a long and rather frayed nose, and an evil little eye. Without any shadow of doubt he was Uncle Phil.

Uncle Phil’s cameo appearance in the programmes ruins the Grigsons’ experience, riddling them with guilt since their television has been purchased with the insurance money from his estate.

Lilliput magazine

The story was first published in Lilliput magazine in April 1953 along with another Priestley story, ‘The Grey Ones’. Lilliput was in circulation from 1937–1960. Although the title of the magazine sounds like it was for children, it was most certainly not, containing some risqué material. It was aimed at a predominantly male audience. Ironically, it was the mass popularity of television which was the death-knell for pocket general interest magazines like Lilliput.

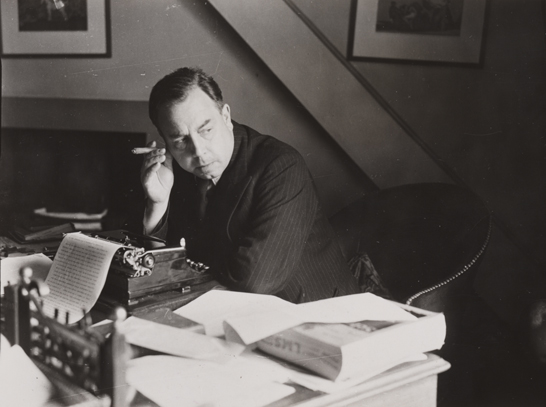

J.B. Priestley’s links to television

J.B. Priestley was far more familiar with television than most of his readers. He had embraced television well before the war, appearing regularly as a presenter on the BBC service at Alexandra Palace.

In 1948, he introduced a documentary about the work of UNESCO. The following year, he appeared in a BBC series entitled Personal Impressions, which invited viewers to see things through the eyes of well-known people. Priestley was the first to appear in the series, and the episode was transmitted on 4 November 1949.

A number of Priestley’s stage plays were adapted for television. He famously looked back on his Bradford upbringing in The Lost City, a 1958 BBC programme which can be viewed on demand in our BFI Mediatheque.

In mid-1955, Priestley wrote and presented the six-part series You Know What People Are, which aired on BBC television. He later wrote that he chose a familiar phrase for the series title because it summed up the mood of the programmes. His aim in the series was to look at how people behaved and talked to each other. Priestley felt television was the right medium for this work, ‘because it allowed for informality as well as being an extremely intimate medium’.

Television and the paranormal

The literary/dramatic device of the family television set being possessed by an unnatural or spiritual force was not unique to Priestley’s ‘Uncle Phil on TV’. Lewis Padgett’s short story ‘The Twonky’ (1942) involved a haunted radio; when the story was adapted into a film in 1953, this became a possessed Admiral 16” television set. Later works of note include Poltergeist (1982), Videodrome (1983), The Friday the 13th: the Series episode ‘The Spirit of Television’ (1990) and, in Doctor Who, ‘The Idiot’s Lantern’ (2006).

Scholars such as Marshall McLuhan (1964) and Jeffrey Sconce (2000) have explained that such tales demonstrate resonance and continuity between television technology and the occult. Television ‘disembodies and disassociates’, so it should not be surprising that the medium of television drives a fascination with such fantasies of the paranormal and more recently, extra-terrestrial contact.