Cast your mind back to October 2020; those of you lucky enough to attend our annual film festival, Widescreen Weekend, may have watched one of four screenings as part of Women in Widescreen: Mother Cutter, a series of screenings exploring the work of pioneering female film editors.

Kill Bill: Volume 1—edited by Sally Menke, Quentin Tarantino’s trusted editor and ‘number one collaborator’—was one of the films shown to celebrate this under-sung contribution to cinema. The three-day lineup also included American Graffiti, the work of legendary editor Verna Fields (affectionately nicknamed ‘mother cutter’, from which the retrospective takes its name); Hugo, the product of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker’s 50-year partnership; and Mad Max: Fury Road, for which Margaret Sixel took home the Academy Award for Best Film Editing.

Alice Miller, part of the programming team at Leeds International Film Festival—which launched the retrospective in November 2019—was responsible for curating the strand. Speaking about the films chosen as part of Mother Cutter, she said: “I’m thrilled we’ve been able to bring this selection to Widescreen Weekend. With this season of films, I wanted to bring a rich yet hidden history of women’s editing to greater attention, to challenge outdated notions of auteurism by looking at films as collaborative works of art, and to celebrate the often overlooked art of editing, a vital and creative work that is not given the recognition it deserves.”

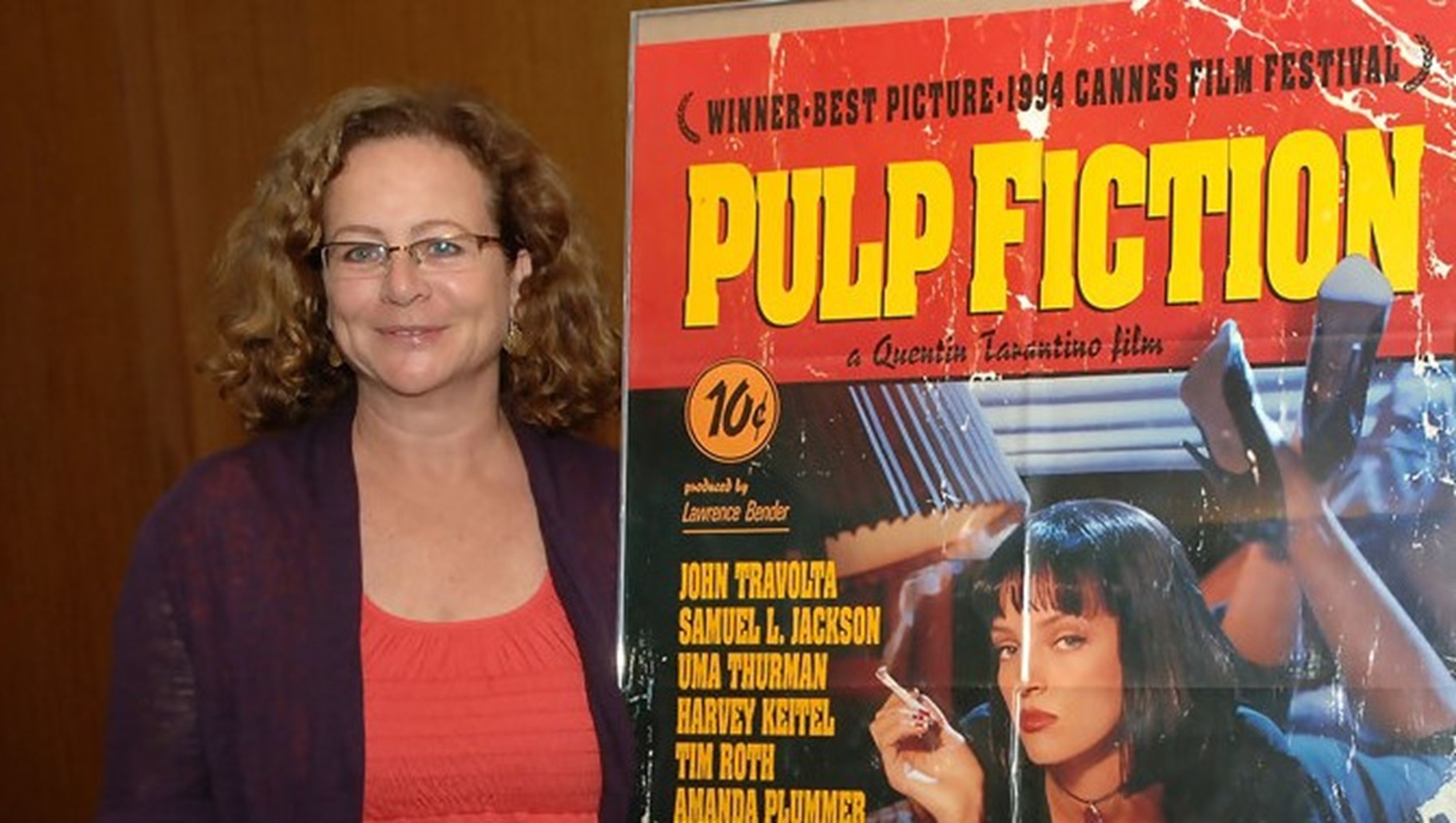

Celebrating the long-standing creative partnership of Sally Menke and Quentin Tarantino, Kill Bill was screened in the warmth and depth of a well-travelled 35mm print, just the way its creator intended. After all, as far as the Oscar-winning director is concerned: “digital projection is the end of cinema.” Watching limbs fly during the monochrome segments of the film’s Crazy 88 showdown, it became impossible to tell the blood spatter from the grain—the physicality of celluloid made visceral.

Juxtaposing languid, dialogue-heavy scenes with bursts of immersive violence collapsing time and ramping the intensity of the director’s genre-hopping soundtracks, Menke’s editing played a crucial role in developing Tarantino’s trademark visual style.

Believing film editing to be a more interesting way to study human behaviour, Menke bailed on a degree in Behavioural Psychology to graduate in Film at the New York University School of Arts. After a decade cutting her teeth on network TV documentaries, her Hollywood break came by way of the 1990 feature adaptation of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles—proving we all have to start somewhere.

Hearing about a young film-maker in need of a good cheap editor, Menke approached Tarantino and was immediately sold on his script for Reservoir Dogs, which for her evoked the tone of her idol, Scorsese. Tarantino’s directorial debut became an instant cult classic, and Menke went on to edit his next six films until her tragic death in 2010.

Kill Bill is a film which wears its genre references on its sleeve, and Menke’s editing techniques are key to evoking the Bruce Lee chop-socky flicks and Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns Tarantino sought to imitate. “Our style is to mimic, not homage,” admitted Menke, “but it’s all about recontextualising the film language to make it fresh with a new genre.”

Menke leveraged the chaos of Tarantino’s hyper-violent action scenes to showcase her flair for fast-paced editing trickery, wryly blending genre tropes of extreme close-ups and swipe cuts with the inventive use of split screens and dissolves to forge a filmic language of her own.

However, Alice believes her editing does more than create pace and rhythm, highlighting a fascination with human behaviour that only grew through the course of her career: “I think to be a good editor, you have to immerse yourself in the mind of a character to the same depth as the director. It’s creating the emotional arc of a film, shaping the trajectory of the characters and helping to realise them. What she likes to do when she edits is watch how a character defines themselves through their gestures and the way they move and select the footage she feels conveys them best.”

In terms of the pair’s working relationship, Tarantino would leave her to put together the dailies with minimal interference, a serious vote of confidence from the director renowned for being a control freak on set—even going so far as to take the strangling of Diane Kruger’s character in Inglorious Basterds into his own hands to create an ‘authentic’ death scene.

Tarantino has always been a vocal champion of Menke’s creative role, acknowledging her as his ‘only truly genuine collaborator’. Once you appreciate the symbiosis between editor and director and the contribution the cut makes to the final look and feel of a film, it becomes impossible to cling to the notion of a lone auteur. Menke, much like the seminal female editors that went before her, was the silent hero behind her director’s success.

As we prepare to reopen Pictureville Cinema this Friday, 21 May 2021, our programme features the work of some fantastic female editors, including Nomadland, edited by director and writer Chloé Zhao (who, in addition to winning the Best Picture and Best Director Oscars for the film, was also nominated for Best Film Editing); The Human Voice, edited by Teresa Font, who has previously collaborated with director Pedro Almodóvar on Pain and Glory; First Cow, edited by director Kelly Reichardt; and our latest Kids’ Club pick Raya and the Last Dragon, edited by Fabienne Rawley and Shannon Stein. You can explore the full film programme on our cinema pages.

Widescreen Weekend will return for its special 25th anniversary edition on 7–10 October 2021.