With 27 days to go until our 30th birthday, the countdown continues.

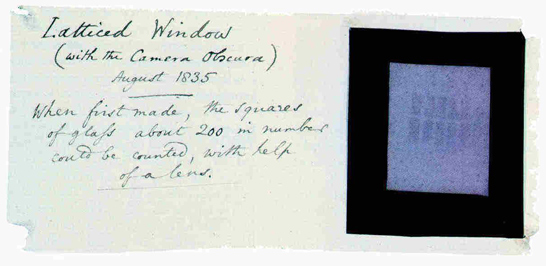

The world’s earliest surviving negative was taken in August 1835 by William Henry Fox Talbot. This negative, a latticed window at Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire, along with several examples of the mousetrap cameras which were used by Fox Talbot to produce these very first photographic images—priceless artefacts from the birth of photography—are preserved in our archives here in Bradford.

In October 1833, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), gentleman, scholar and amateur scientist, was honeymooning on the shores of Lake Como in Italy. Like many travellers of the time, he attempted to sketch the beautiful scenery. However, despite his many other talents, Talbot was a poor draughtsman and the results were, in his own words, ‘melancholy to behold’.

Frustrated by his lack of artistic ability, Talbot dreamily reflected on the perfect yet elusive images created by the camera obscura, a popular artists’ drawing aid. This, he later recalled, was the moment of inspiration which led to the invention of photography.

How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!

Upon his return to England, Talbot immediately began experimenting with paper made light-sensitive by coating it with silver salts. He soon succeeded in making what he called ‘photogenic drawings’—negative, silhouette images of objects such as leaves or lace, produced by direct contact-printing.

Naturally, Talbot also tried to capture images directly from nature by placing his photogenic drawing paper in a camera obscura, but found that the comparative insensitivity of the paper, combined with the limited aperture of the lens, meant that an image was obtained only after a very long exposure.

In the summer of 1835, helped by a spell of particularly sunny weather, Talbot tried again.

Crucially, he had by this time devised a process of improving the sensitivity of his paper. He had also correctly reasoned that exposure times could be shortened by using a camera with a small image size and a large aperture lens.

Consequently, Talbot had made a number of small wooden boxes—two- or three-inch cubes, which he fitted with lenses taken from the eyepieces of telescopes and microscopes.

There is an undocumented tradition that these first photographic cameras were made by a local carpenter named Joseph Foden. Some, however, are too crudely made to be the work of any self-respecting craftsman. One camera, possibly the earliest, was made by simply sawing what looks like a cigar box in half, so it is quite possible that Talbot made at least some of them himself.

Talbot placed these boxes around the family home, Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, and waited for the sun to work its ‘little bit of magic’.

In a letter, Talbot’s wife, Constance, wrote about the what might be perceived as eccentric behaviour of her husband and referred to these little boxes as ‘mousetraps’. The name has stuck and they are now usually referred to as Talbot’s mousetrap cameras. On reflection, they do indeed resemble simple traps, designed in this case, however, to capture the sun rather than unwanted pests.

The world’s earliest surviving negative, of a latticed window at Lacock Abbey, was taken using one of these little cameras. The negative is stored safe and secure in our archives. Unfortunately it is too fragile to be out on permanent display. I’ve been working at the museum for nearly 30 years, and yet I’ve only seen it twice! You can see a copy of the negative alongside one of Talbot’s mousetrap cameras in our Kodak Gallery.

To share your memories of the museum in the run-up to our 30th birthday next month, leave a comment on this post, on Facebook or Twitter.

I brought some students to the media museum and we were looking at an exhibition, I forget who. One of my students got very excited and I asked her why. She asked if this was photography, a question which confused me. She later explained that that was the moment that she ‘got it’. Her work changed dramatically after that.

good

When we visited Lacock Abbey some time ago I photographed the window on my modern professional camera. It is still an interesting image and I now use it as the wallpaper on my computer. This seems to show well the differences in photography over 185 years.