Often when you think of television, your mind skips straight to your favourite programmes. But TV is more than shows—it’s also advertising, researching and scheduling. The aforementioned elements are all explored in the National Science and Media Museum’s Experience TV gallery, but this post will focus specifically on advertising and the history of influencing.

In the present day, most of us associate the term ‘influencer’ with the Instagram-famous who use the app as a platform to promote products in exchange for payment. Some of them originate from reality shows such as Love Island or Geordie Shore, while others build their fame through YouTube or TikTok. But these weren’t the first celebrity trend-setters to come out of TV. To understand how modern influencer culture came to be, we must take a trip back in time—to the 1970s.

The 1970s have been characterised as a time of change, a pivotal point in world history. They also saw the ascent of Delia Smith, a British TV chef after whom the term ‘the Delia Effect’ was coined. The Delia Effect can be defined as the high-profile recommendation (usually by a celebrity) of a product which in turn results in overnight success.

During an episode of Smith’s first cookery show, Family Fare (1973–75), she recommended a lemon zester. After the episode aired, Britain suffered a shortage of lemon zesters… and this was as Smith’s popularity was only just beginning.

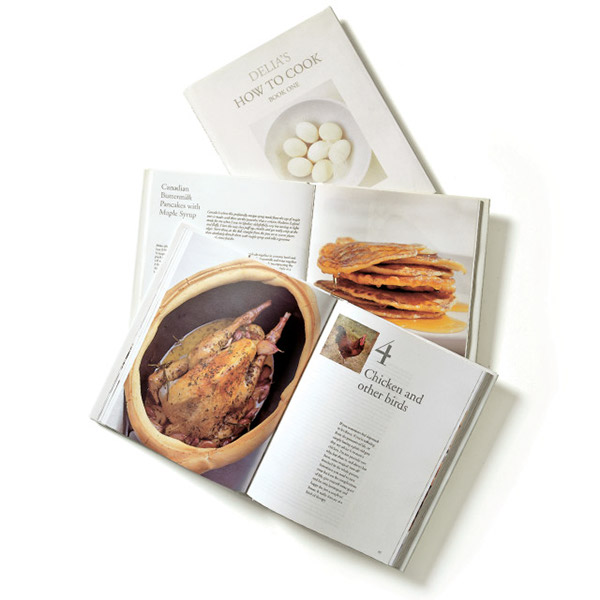

Smith’s fame continued to rise, and reached its height with the 1990s show How to Cook. Her frequent use of eggs on the show caused a 10% increase in British egg sales. In addition, Smith’s recommendation of using skewers to check whether a cake is thoroughly baked caused a 35% increase in sales. By 2001, Smith’s impact on the food industry could no longer be ignored, and the Delia Effect was added to the Collins English Dictionary.

Today, it might seem surprising that Smith’s impact was considered such a phenomenon. But it truly was, and it occurred in a world unequipped to deal with it. In fact, the BBC was forced to begin warning companies as to when their products would be used in Smith’s programmes to allow them to prepare for the inevitable surge in sales.

However, this was free advertising: Smith refused payment in return for featuring products and only began advertising for food companies, such as Waitrose, after retiring from TV. Smith argued that paid promotion lacked integrity and that her audience would begin to distrust her opinions. Plus, at the time, advertising brands on a BBC programme violated the network’s policy. This gave Smith’s recommendations a level of credibility that is often lacking in product promotion today.

Product promotion in TV has evolved drastically since Delia Smith’s days at the BBC. Reality TV, in particular, has affected this; take, for example, a show such as Love Island. Though it’s nominally focused on dating, the show’s popularity means its participants are quickly transformed into minor celebrities, with many of them going on to leverage this fame to become influencers. It might appear that their careers as advertisers are launched on social media after exiting the infamous ‘Villa’. But while on the show, the contestants are frequently required to showcase free products—everything from clothes to smartphones—which essentially trains them in how to approach and promote a brand deal.

Love Island is basically survival training for a career as an influencer, and it can be argued that many contestants’ main motive for applying to be on the show is to boost their profile and engage with brands. This is in stark contrast to Delia Smith, who effectively promoted products by accident rather than as a business exchange.

Comparing the two demonstrates how product placement in TV shows has evolved from genuine product use into a mutually beneficial business transaction. However, sales statistics suggest the development of the influencer-brand relationship may have had little effect on the consumer. British clothing brand Missguided, who sponsored Love Island in 2018, reported a 40% increase in sales each night the show aired. This is an impressive result, highlighting how susceptible consumers are to products advertised through TV. But the number almost matches the rise in skewer sales caused by Smith’s endorsement 20 years earlier.

By 2019, Missguided had been replaced with a new clothing sponsor for Love Island, I Saw It First. Viewers may have wondered why, since the association with Love Island was clearly beneficial for Missguided. The increasingly critical conversations around the show, questioning its lack of diversity, could have had an impact; Missguided were also criticised for using overly sexualised imagery in some of their adverts. So there is a detrimental aspect to such high-profile product promotion: brands and influencers can unwillingly be associated with negative discourse that may be damaging to their public reputations.

It’s clear the Delia Effect paved the way for future influencers by establishing a direct correlation between celebrity endorsement and sales. But Smith understood the dangers and negative consequences of product promotion, where contemporary influencers often overlook them.

So perhaps it’s accurate to call Delia Smith ‘the original influencer’. In fact, her credibility and trustworthiness suggest she is the purest, most uncorrupted form of an influencer—one that reminds consumers to consider the authenticity of the products advertised to them on TV.

If you’d like to learn more about the history of advertising and its iconic figures (including Delia Smith), visit Experience TV on Level 3 of the National Science and Media Museum.