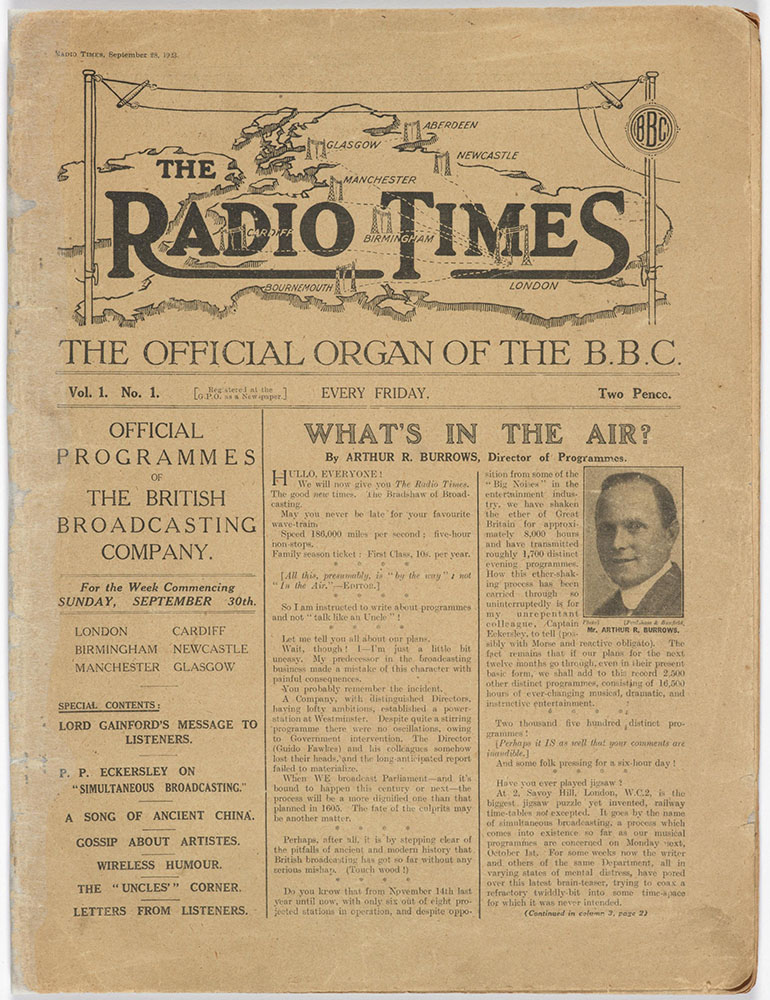

The first broadcast was read by Arthur Burrows, known as Uncle Arthur. Having previously held a position as a journalist for the Oxford Times, Burrows joined the BBC as Director of Programmes. He would be one of the first people ever to make the move from newspaper to broadcast reporting.

The first broadcast began at 18.00 on 14 November. Burrows read a news report twice (first quickly, then slowly), and asked listeners to let the BBC know which speed they preferred. The news that Burrows read would have been provided by Reuters, a government-approved news agency. In the early days, the BBC was not allowed to report its own news for fear of broadcast media being a strong competitor against newspapers. The BBC did not gain the right to edit the news they received until 1934, and even then it wouldn’t be until the Second World War that they were allowed to broadcast before 18.00. It was assumed that after that time, everyone who was going to buy a newspaper for the day already would have, and so it was safe to broadcast the news without threatening newspaper sales.

After the news report, the BBC broadcast its first ever weather forecast. This was not a weather report as we know them today, but instead a shipping forecast that described the Met Office’s predictions for the seas around the British Isles. Weather broadcasts that might give you an indication whether you needed a jumper or a brolly wouldn’t begin until March 1923, and the TV weather map we know today wouldn’t be on screen until 1949.

The BBC’s first broadcasts came from its London studio, using the 1.5kW transmitter that today sits in the Science Museum’s Information Age gallery. Originally, three transmitters were designed, but it was the 1.5kW transmitter that was advanced enough for the job when 2LO was preparing to launch. The same transmitter then remained in service for three years before it had to be replaced.

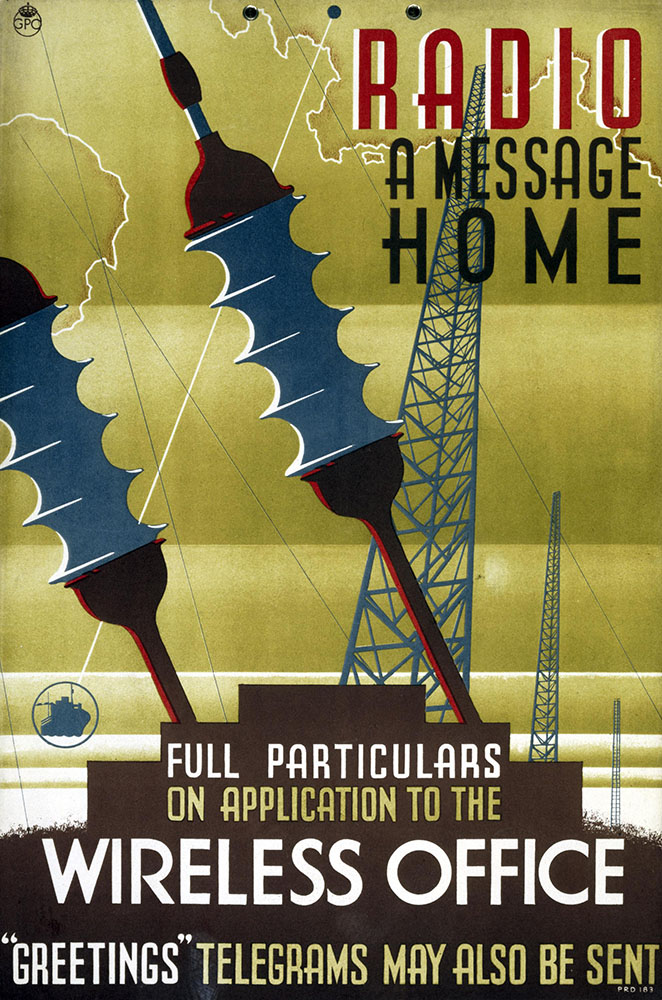

The London broadcasts became affectionally recognised by the opening, ‘this is 2LO calling’. 2LO came from the identification number granted to Guglielmo Marconi on the broadcasting license from the General Post Office. At this time, the GPO controlled all communication in the country—from letters to telegrams, and telephone calls to radio waves. It was demonstrative of how rapidly new technology emerged that there was not yet a separate infrastructure to deal with broadcasting, like we have today.

While London was home to the first BBC radio station, it was not the only home of the BBC in the 1920s. Just 24 hours after 2LO launched, Birmingham and Manchester launched their own BBC radio stations. Other stations soon followed, with each station just as important as 2LO.

Part of the reason programmes were broadcast locally was because of the limits to transmission technology at the time. To reach more remote locations, some stations were set up to repeat services from central areas. This was how 2LS, a station just for the Leeds and Bradford area, was born in 1924. 2LS relayed broadcasts from the Manchester (2ZY) station, and had some ability to produce their own shows. From 2LS came local legend Maud Hummerston, the first Northern Auntie of the BBC. Originally a children’s storyteller at Leeds Public Library, Humberston joined the Leeds relay station in 1924 and worked there for four years, reading stories to thousands of children over the radio. We have documents related to her in the Science Museum Group collection.

As time went on and transmission capacity improved, John Reith (the Director-General of the BBC) wanted to ensure the BBC provided the ‘best in every department of knowledge’. At this early stage in communication history, ‘the best’ tended to be based in London and would be easiest to broadcast from London. This led to the centralisation of the BBC around the capital, where experts could quickly be called upon to speak in the studio.

With London becoming the central hub of broadcasting, some of the main city stations closed, as well as smaller relay station like 2LS. The BBC set up a national programme that divided the country into four: the South was based in London; the West, including Wales, was centred around Bristol; the Midlands was based in Birmingham; and the North, stretching from Lincolnshire to Scotland, was based around Manchester’s 2ZY.

Between the wars, the North became well known for its distinctive style, far removed from the tone of 2LO. One popular broadcaster was Olive Shapley, who had been born into a lower-middle-class family in Peckham. She was one of the first producers to leave the studio in a recording van and go out to interview ‘ordinary’ people. One of her live programmes, Men Talking, featured miners from Durham and led to the advent of scripted broadcasts—as this was the best way to stop guests from swearing while on air.

Although the BBC was not only based in London, local radio for local people (and not just region-based shows) was lost soon after it started. It wouldn’t be until 8 November 1967 that the BBC would bring back local radio networks, firstly with radio Leicester. This move to smaller experimental networks was so significant that Leicester opened with a speech from the Postmaster General and the Lord Mayor of Leicester.

In 1969 the BBC decided their experiment with Leicester, and later Sheffield and Merseyside, was a success. They gave permission for the number of stations to be expanded, and today there are 40 local radio stations under the BBC, telling local stories to local people.

The BBC has come a long way since Burrows’ first announcement for 2LO. From the Corporation’s first experimental television broadcasts in 1932, to the advent of colour in 1969 and then the launch of BBC iPlayer in 2007, they have continuously pushed the boundaries of technology and challenged the definition of broadcasting. Throughout this, there has been a certain commitment to telling stories both for and from different areas of the country. 99 years ago the BBC was born, and while London may have been first, Manchester—and Bradford—were not too far behind.

What a marvellous, evocative Science Museum exhibit – the original 2LO transmitter of 1922. More than ingenious, it is also handsome. Form & function, and all that.

The circuit is barely more complicated than my 1924 Marconi radio – still working well.

Can you imagine modern times offering anything to equal those early broadcasts? Chief engineer playing piano and reading childrens’ stories, listeners making their own ‘crystal’ sets to tune in, then the small BBC team gradually spreading its transmitter network across the nation, and onwards to an ‘Empire’ service.