After our discussion about art cinema and the specialised film sector, the ‘What is Cinema Now?’ course moved on to consider the role of mainstream cinema, focusing on Sacha Gervasi’s Hitchcock, a biopic of the legendary British director and his attempts to film and release what is thought by many to be his masterpiece, Psycho.

The film provides an interesting contrast between the role of mainstream cinema in recent years, and its role fifty years ago during an era when films like Hitchcock’s were finding wide release through Hollywood studio funding and distribution.

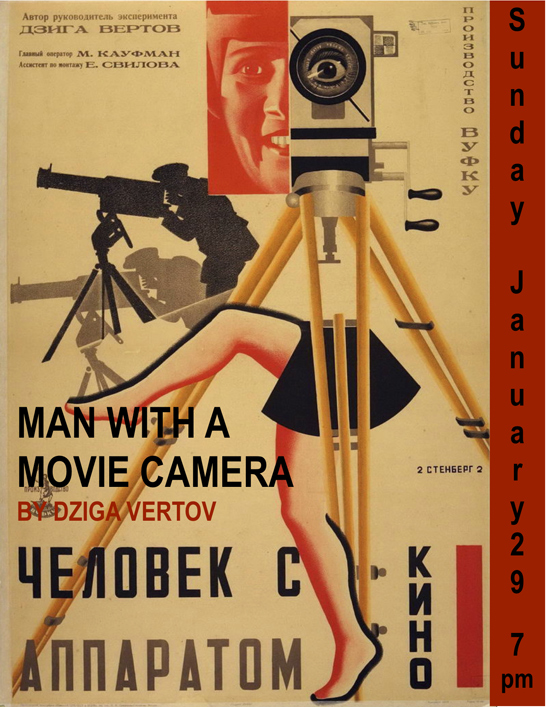

Alfred Hitchcock is a curious subject of study as he is perhaps the best example of a mainstream film-maker being treated as an artist, with his work triggering a host of studies and analyses in his lifetime (most notably by the influential Cahiers du Cinéma and its foremost critic, and future film-maker, François Truffaut). A 2012 edition of Sight and Sound ranked Vertigo, his masterful piece on loss and obsession from 1958, as the greatest film of all time (outranking more specialised and art oriented pieces such as Ozu’s Tokyo Story and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera).

Hitchcock admitted that the success of his films from both a commercial and critical standpoint rested on his utilisation of a ‘pure cinema’, an ability to tell a story solely through editing, camera placement, sound and mise-en-scène (a term to encompass such visual aids as lighting, set design and art direction which, when placed together, create an overall impression of a single shot or scene) rather than through dialogue.

This is where Hitchcock’s style deviates most significantly from that of film-makers working with more artistic material and from more specialised backgrounds: whereas most art cinema encourages the audience to interpret its content, Hitchcock’s pure cinema demands an immediate and controlled emotional response. He often spoke of playing his audience like an organ, a fact mirrored in one scene from Gervasi’s film in which Hitchcock, played by an elegantly jowelled Anthony Hopkins, waits in anticipation for the audience reaction to Psycho’s infamous shower scene during the film’s premiere, and walks away with satisfaction when the desired screams and shrieks come forth.

This raises questions: to what extent can mainstream cinema be considered art, compared to a film like What Richard Did, which asks its audience to think for themselves? And at what point do films cease to be merely entertainment?

A film like Hitchcock can certainly be considered ‘merely entertainment’. With its period setting and attention to detail, the film plays to postmodern notions of nostalgia and comfort in the familiar. Like last year’s other Hitchcock biopic The Girl, Hitchcock uses the director’s famous, enigmatic persona to offer something immediately recognisable, rather than challenging the audience’s perceptions.

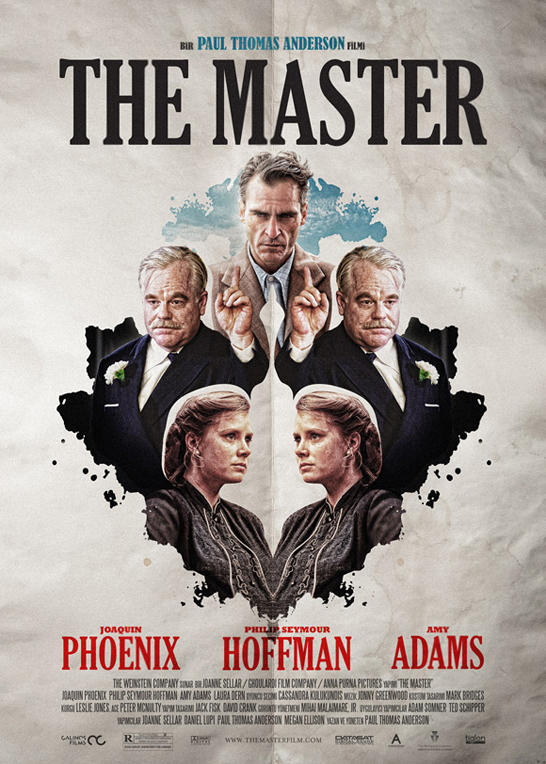

Hitchcock is unlikely to be considered great art in the same way as Psycho or Vertigo, but that does not mean that there is no space within modern mainstream cinema for great art to arise. Notable recent examples include Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master and Terrence Malick’s To the Wonder; both were released through the mainstream and feature big names (Joaquin Phoenix, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ben Affleck et al) yet possess the impressionistic and contemplative qualities that more appropriately place them in the strata of art cinema.

Pushing on from mainstream cinema, the course turned to documentary cinema. Formerly a subset of specialised cinema, documentary cinema has achieved greater mainstream recognition following on from the success of films such as Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine and Andrew Jarecki’s Capturing the Friedmans. The popularity of these films has led to a new wave of films that can be considered ‘high-concept’ documentaries, such as last year’s The Imposter, which, adhering to the adage that truth is stranger than fiction, imposes a narrative on real and often unbelievable events.

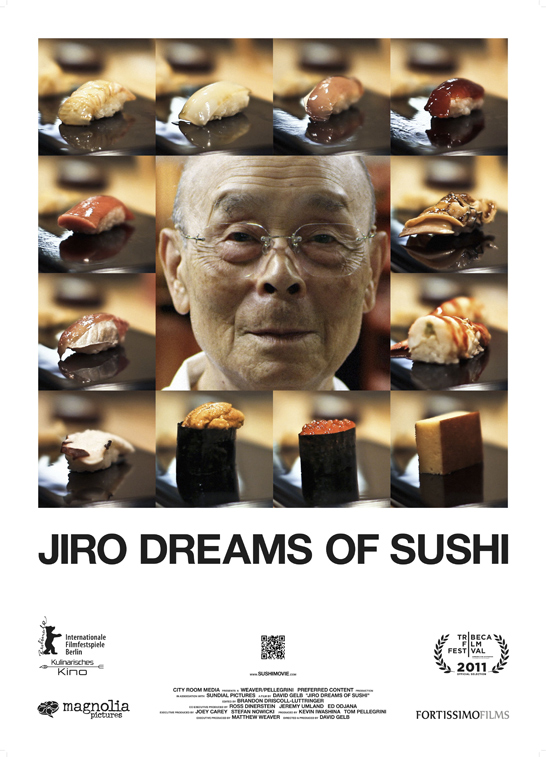

David Gelb’s Jiro Dreams of Sushi can be considered to be a piece of traditional documentary cinema. Documenting the work of Jiro Ono, one of Japan’s most revered and celebrated sushi chefs, the film dispenses with narrative to show a portrait of the man’s life, his methods of work and his relationship with his two sons who have dedicated themselves to continuing their father’s legacy. Like many specialised films, Jiro Dreams of Sushi does not demand an emotional response from its audience, but reveals Jiro’s life without judgement, leaving the viewer to form their own opinions and impressions. Is Jiro a dedicated artist, or an obsessive workaholic? Is he a domineering patriarch, or are his sons choosing to follow in his footsteps as a sign of respect to their father?

Like many documentarians, Gelb leaves himself and his opinions out of the film. This distance raises the question of whether Jiro Dreams of Sushi is art.

In his book Film and I, Bengali film-maker Ritwik Ghatak states that film is ‘a matter of personal statement’ that bears the impression of ‘a collective personality’ or of ‘one individual’s temperament upon all others’ creative activities’. He asserts that all art can only be considered art if it bears the imprint of one’s own self-expression, adding that ‘raw meat is not exactly a Moghlai kebab. A cook comes somewhere in between. A cook that is the artist’s personality’.

With this in mind, can we consider documentary film like Jiro Dreams of Sushi to be art if they do not bear the imprint of an artist? If so, then does that make mainstream material which conforms to notions of the auteur theory (as the films of Hitchcock do) more artistically valid than documentary film-making, which challenges its audience to think rather than feel?

3 comments on “When does film become art?”