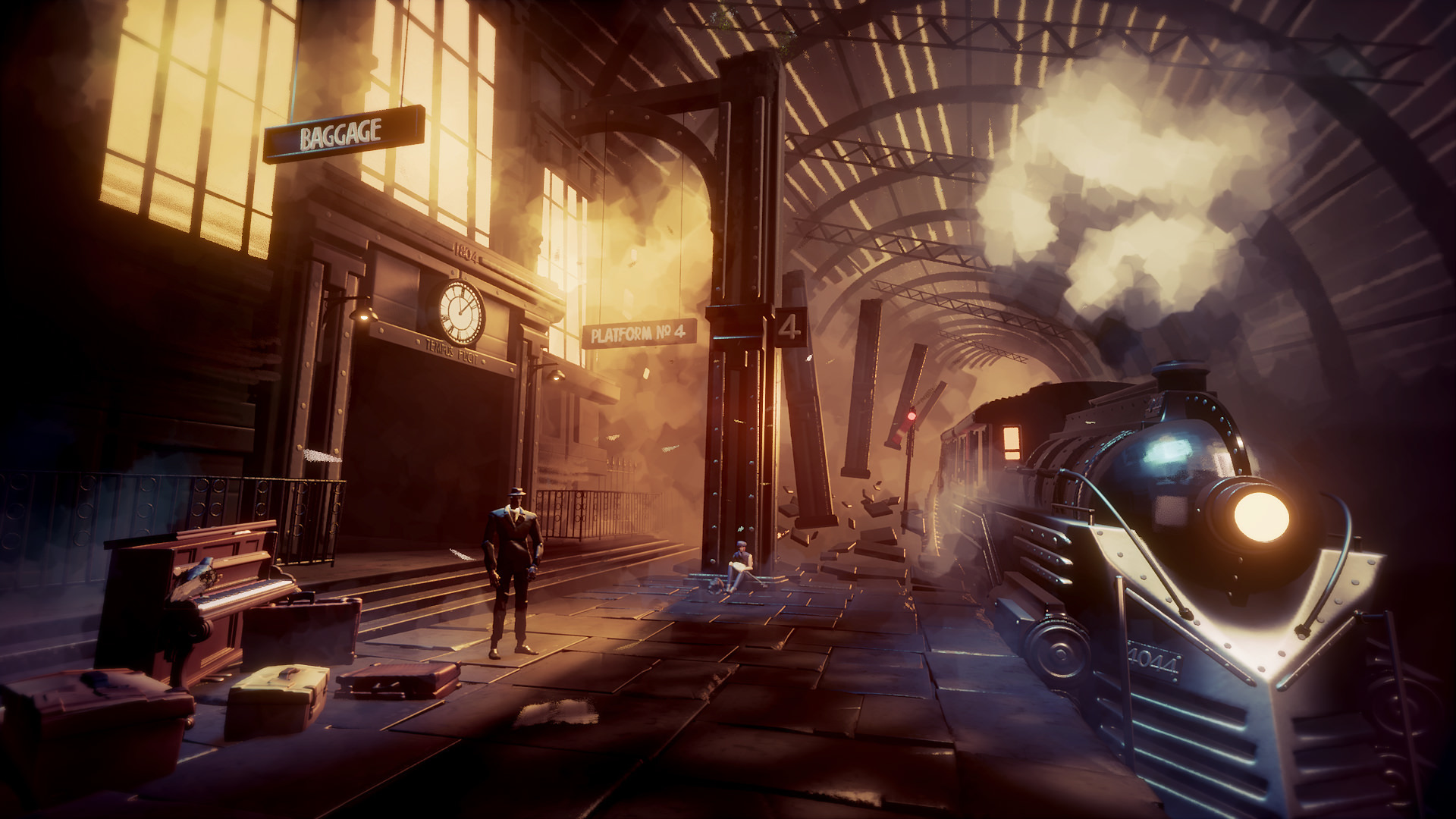

This year we are very lucky to play host to developers from the first party Sony videogame studio, Media Molecule, who will be showing us their upcoming game Dreams. Dreams is already being hailed as one of the most impressive PlayStation titles to date due to its almost unique balance between usability and creativity. The player can use the game as a simple tool to create games; however, they can also choose to make movies, produce art, record albums and create cartoons. What’s more, the player can opt to do this on their own, or can work collaboratively by downloading the creations of other players.

While Dreams represents a significant achievement in muddling the distinction between gameplay and games development, it’s not the first game to give players the apparatus to shape their own experience. Allowing users to create their own modes, maps, characters, stories and even entire games has long been an important component of game design.

The games industry’s preoccupation with customisation and creation could be considered a remnant of our analogue past. Before the digital era, the worlds and characters we created were limited only by our imaginations and the rules established by pen, paper and the roll of the dice. This influence carried over to digital gaming through level editors such as 1983’s Lode Runner, for the Apple II, and Boulder Dash, as well as custom games where players could alter parameters of the virtual world or its inhabitants to change gameplay.

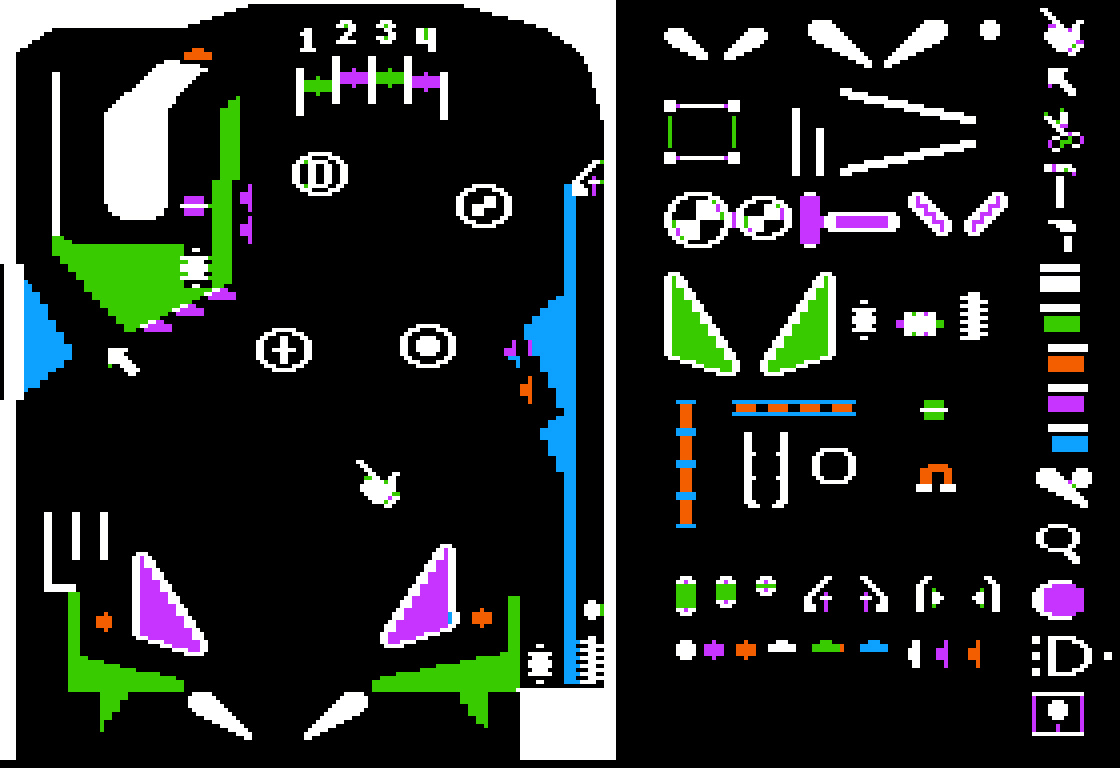

In 1982, Pinball Construction Set was released for the Apple II. It used a drag-and-drop interface to allow users to make their own Digital Pinball Tables, controlling everything from layout and colours to game logic and physics. This represented a major leap forward in offering players the ability to make a game their own. It could be considered an early instance of modding (alterations made to a game by someone other than the licence holder).

Fast forward a few years, and level editors and custom games had become a widespread phenomenon: the Tony Hawk, Far Cry and Halo series all boasted popular examples of custom map editors. Many players enjoyed the freedom these ‘sandbox’ levels provided and the emergent gameplay that ensued, with simple mechanics interacting to create unintended complex results. (See also: the hundreds of hours I’ve spent in Halo: Reach Forge mode.)

Map editors often give the player a tiny portion of the assets and utilities that could be accessed by the developer—yet they have still been enjoyed and even exploited by players in the quest to do more with their games. Many modern games now include modes which allow for taking pictures or videos and editing together films of gameplay; if the creator chooses, these endeavours can be circulated online and enjoyed by anyone.

Publishers and developers often encourage this sort of behaviour by including player creations in the main game—or even offering them jobs. When they took over the LittleBigPlanet series, Sheffield-based developer Sumo Digital chose to hire most of their level designers for LittleBigPlanet 3 from the game’s existing user community. Moreover, many popular and beloved game series of recent years, such as Counter-Strike, DOTA, Dear Esther, The Stanley Parable and Team Fortress, have started off as mods before becoming fully realised as independent titles in their own right. These instances demonstrate that there is a significant value in players who enjoy playing games inventively and using their games as creative tools.

In the past few years we’ve seen a few games which have really made a considerable effort to provide players with software that’s as playable as it is creative. Nintendo used assets from its beloved series to create Super Mario Maker (2015), allowing players to share and play levels from other users. In 2013, Microsoft Studios launched Project Spark—a digital canvas on which players could make and share games—to little success; the platform failed to take off, even though many praised the software as one of the most user-friendly creation suites to date.

Media Molecule stated their goal for LittleBigPlanet through its tagline: ‘Play, Create, Share’. Initially a platforming game in its first couple of iterations, LittleBigPlanet grew to facilitate creation of many game types such as racing, fighting and puzzle games. The series is praised as a landmark title due to its ease of use and its advocacy of players as creators. It was from this success that Dreams was envisioned.

It seems that creation is almost intrinsically tied to the enjoyment of videogames, whether it’s by creating your own avatar and shaping the virtual world with your choices, or by sculpting your environment from scratch and sharing it with the world. Game developers have identified how simple creation engines can inspire future games makers and are steadily becoming more ambitious with their software. What were once essentially simple tools now have the potential to further obscure the relationship between consumer and creator.

The Yorkshire Games Festival takes place 6–10 February 2019 at the National Science and Media Museum. Explore the full programme online.