Abbi Senior (AS): To get us started, please could you introduce yourself?

Vanessa Torres (VT): I am Vanessa, a Conservator at the National Science and Media Museum and I’ve worked here for 10 years. I am a paper conservator by training but, prompted by the nature of our collection here at the museum, photography conservation has become my passion—I really get on with the materiality of these objects and I find it fascinating, so I really feel like I’m in the right place!

As a result, I have invested a lot of time and effort into developing my knowledge about photographic materials and how to successfully conserve them for the future.

AS: In your own words, what is a microfading tester (MFT)?

VT: To put it simply, microfading is a sped-up method for assessing how sensitive light individual objects are. Using this piece of equipment means that we don’t have to rely on hypothetical assessments but have accurate and specific data for the individual objects to support us making decisions.

AS: Why is it useful?

VT: Our photography collection encompasses everything from the unique to the mass produced. We hold some of the earliest photographs in the world, which were taken using more experimental processes, as well as photographs made with very common processes and materials.

When looking at them, you can identify the visual differences between each photograph, but in terms of materiality and light sensitivity, they can vary significantly. Sometimes you find that some of the earlier processes are more light stable compared to more modern processes.

We know that it is our purpose as a museum to make the collection accessible. This means that the objects are studied, handled, viewed and displayed by researchers and museum colleagues. However, all of these activities require exposing objects to light.

Light exposure can be incredibly harmful to these objects, and it is up to us as conservators to make decisions on the suitability for display of light sensitive objects. These can be made based on our knowledge of materials, knowing how they interact with one another and the surrounding environment as well as naked-eye inspections.

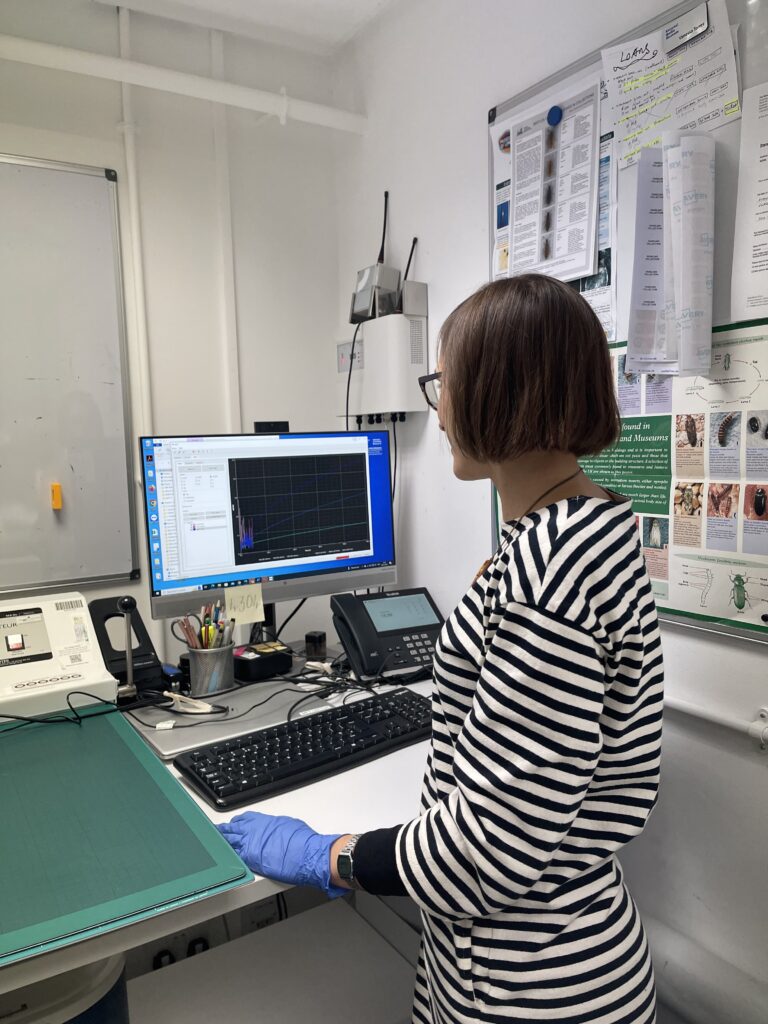

By using scientific conservation equipment, such as the microfading tester, within these assessments, we have the opportunity to understand each object’s light stability in much greater detail than we’ve had previously. This means that we are able to make more informed evidence-based decisions and mitigate any further damage to the object in the future while making it accessible.

AS: How does the microfading tester (MFT) work?

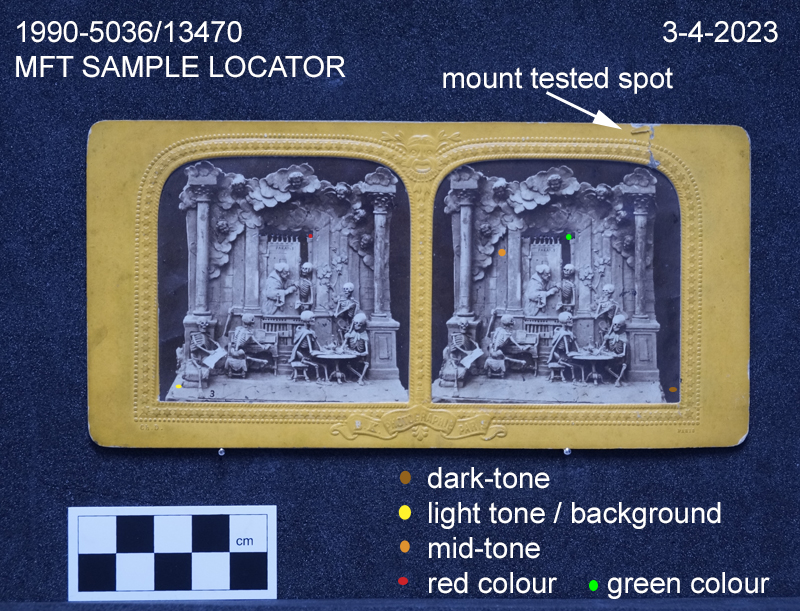

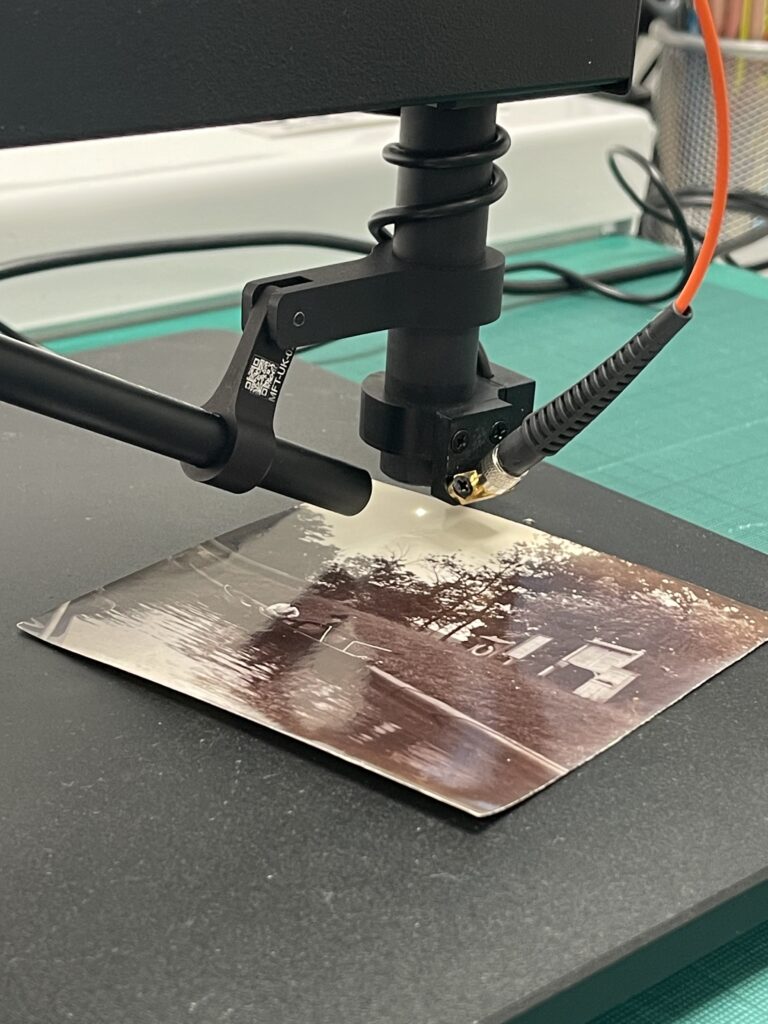

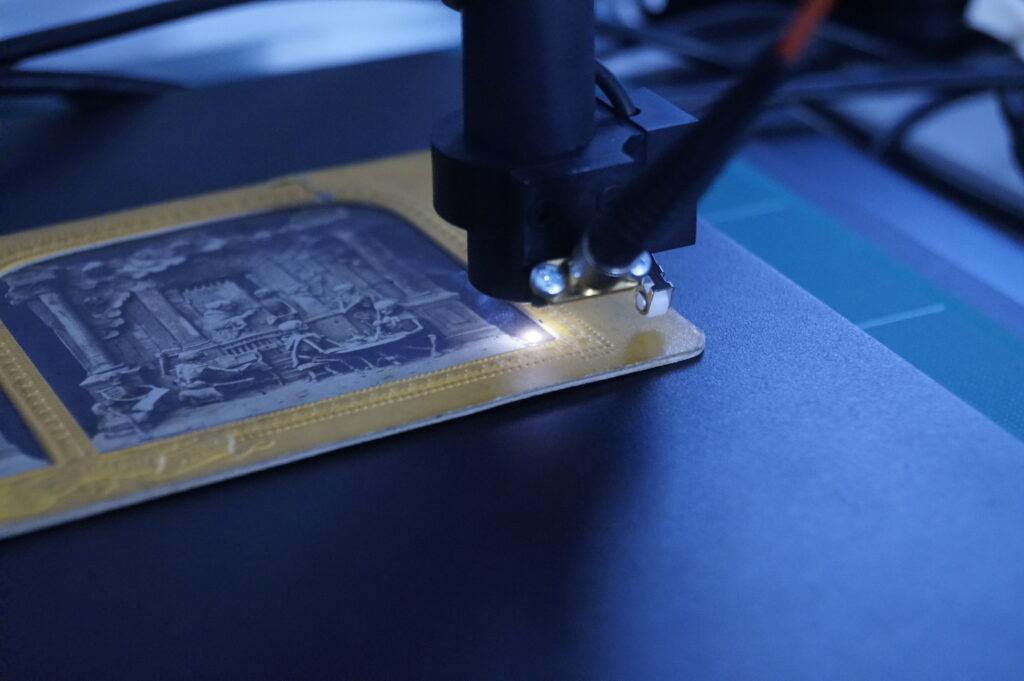

VT: The microfading tester uses a tiny spot of very intense light to measure colour changes in objects that are sensitive to light exposure—mimicking an on-display environment on a tiny scale. The instrument continuously records the change in the colour over the tested period, which I can see in real time in a laptop next to it. I am able to set the duration of the test—typically it takes a few minutes, but I can manually stop it at any point if necessary.

To interpret the data given by the instrument, the measured rate of colour change needs to be compared against a relative scale. At the museum, we use the Blue Wool Standards, and the MFT is set up to distinguish between BWS 1 to 3, which are grouped together as being the most light sensitive.

AS: How do we use the microfading tester (MFT) in the museum?

VT: In this museum, we predominantly use it on paper-based objects and photographs which have been selected for short and long exhibitions,with our collection often being requested for display in our own SMG exhibitions and for loans nationally and internationally.

AS: Tell us about your favourite object you’ve worked on with the MFT?

VT: In 2021, I tested the light sensitivity of a new polymer £50 banknote which was acquired by the Science and Industry Museum. It was to be displayed in the Top Secret exhibition as it features an image of mathematician and scientist Alan Turing.

However, before I could even begin testing, the first hurdle to overcome was actually being able to withdraw a new polymer £50 note from the bank—I had to go to several banks to find one!

In between my trips to the bank, I contacted the Bank of England to request information about the materials of this new polymer banknote. I was told that:

- The polymer material and security features aren’t light sensitive – so you can expect no yellowing or damage to be caused by exposure to artificial light

- The most risk of sensitivity is the pigments used within the printing inks, similar to what we have with other printed materials

- The majority of the colours on the £50 note have excellent light fastness

- The other colours/inks in the note will be fine for many years providing they are kept away from direct sunlight for excessive periods of time. Any incandescent, fluorescent or LED artificial lighting is fine, protection from any UV component wavelength even better.

- Furthermore, according to ISO 105-B Blue Wool Standard the UV fluorescent yellow/red are rated BWS 3 to 4 and the other inks are rated BWS 5+.

After having success at one of the banks, we at last had the bank note in our possession and I decided to test it for safety’s sake. Needless to say, all of the above information was confirmed by the MFT and with that the note went safely on display as part of the exhibition.