Stuck for what to do on a rainy summer’s day? Why not watch the 1969 BBC broadcast of the Moon landing? Or maybe the first time the doctor regenerated into another one on Doctor Who back in 1966. Perhaps settle down for a good old chuckle at the early antics of the Walmington-On-Sea Home Guard platoon in Dad’s Army… Well, you can’t—but there is a reason why.

We don’t think of television as a disposable medium, but from its inception right up to the 1980s that was exactly how it was regarded. There are great swathes missing from television archives: 97 episodes of Doctor Who are still missing, 514 editions of Top of The Pops are unaccounted for. And as for one of the most popular shows of its time, Juke Box Jury, only two out of 432 programmes remain.

Let’s look at some reasons why there are so many gaps in our broadcast history—they are less reckless than you might expect.

No recording was ever made

This might seem strange to us in the digital age, but in the early days of radio and television, broadcasting was primarily a live activity. There was initially no, and later limited, means of recording a programme. This means that there is extremely little evidence of the earliest television broadcasts.

Recordings were made for short-term broadcasting reasons, not for the long term

When recording technology was more available, it was mostly used for practical purposes, such as playing the programme again on another day (the origin of the repeat), or when a recording had to be made on location away from the studio. The idea of making recordings of important or historical events developed inconsistently and very gradually.

Making recordings was very expensive

In television, videotape recording began to be available in the 1950s. The recording machines could cost the equivalent of £300,000 and the 2-inch tape could be as much as £2,000 each in today’s money. These costs were a huge incentive to record over existing programmes, until the tapes were so worn out that they were binned.

Creating television archives

There are several more reasons, such as re-use rights, value and commercial opportunity. But one of the biggest factors was that there was no requirement to build an archive. This was only rectified as late as 1981 when it was written into the BBC charter that archives were required to be kept.

It is estimated that around 60–70% of the BBC’s output between the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s was deleted. However, this wasn’t the end of the story. Before wiping the videotapes for re-use, many were transferred onto 16mm black and white film. This was for selling abroad where videotape wasn’t always compatible, allowing the cheaper prints to travel abroad while the original videotapes were wiped.

The prints travelled as far as Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Hong Kong among hundreds of other countries. Once they were returned to the BBC they were marked with a ‘certificate of destruction’ and incinerated. Television companies around the world could also be asked to destroy them rather than send them back.

So, what have we got left to look back on of television from the 1950s to the 1970s? Well, still quite a lot. Once archiving became mandatory, the hunt was on for any 16mm prints of lost television shows to fill gaps in the archive. An example of this treasure hunting can be seen in Doctor Who. In 1981, just 57 episodes of the 253 made existed. In 2024, 156 episodes are now known to exist. Some episodes have been retrieved through normal means such as overseas broadcasters returning prints that they never destroyed, and the BFI had episodes deposited with them because some were made on film. There were also returns from unconventional places such as car boot sales, garden sheds and a full story found in the basement of a Mormon church in Hong Kong.

Even if the physical copy didn’t exist there were other ways to see lost media. Some TV fans made audio recordings of their favourite shows by holding a microphone to the TV speaker. Others chose to point an 8mm cine camera at the screen to capture moments of their favourite shows.

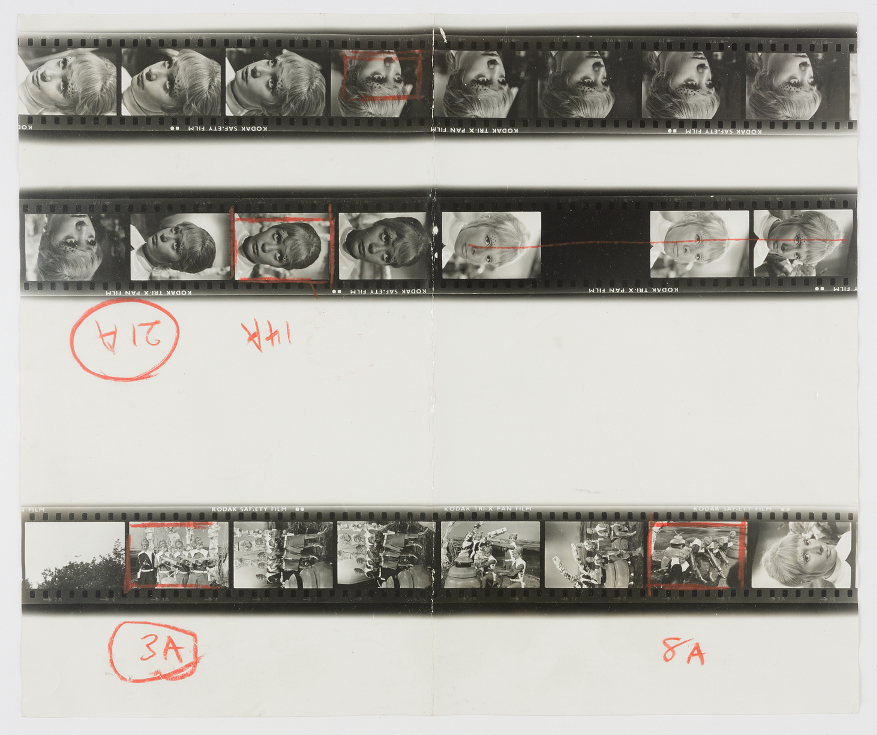

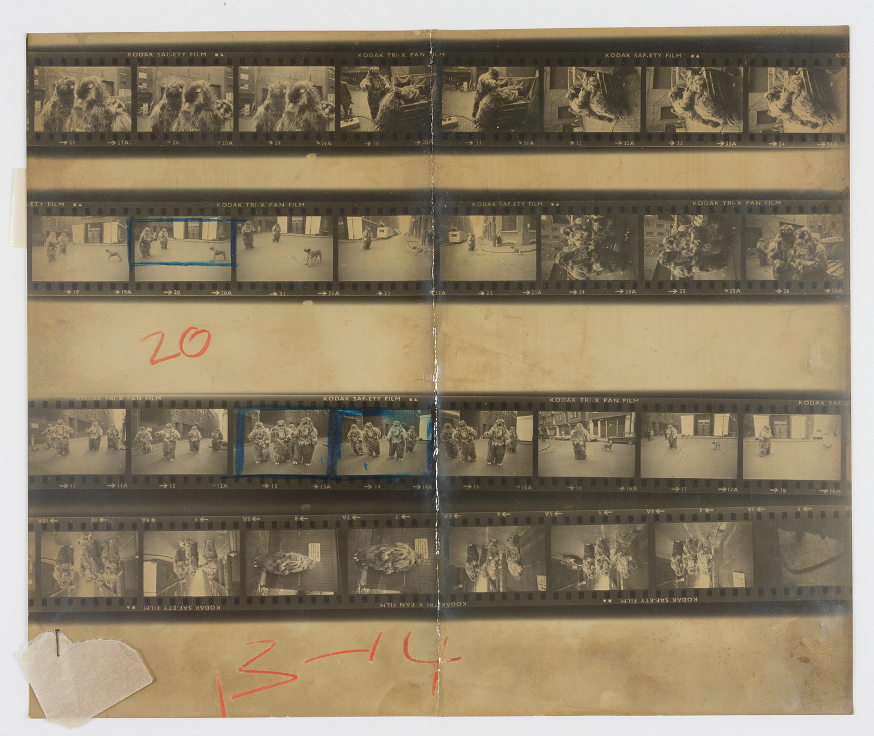

There was John Cura, who was commissioned by actors, directors and producers to create ‘telesnaps’ of their work. This involved him rigging up a special device to take live photographs of the tv screen as the programme went out.

The press of the time also gives us an insight into lost broadcast media. These pictures from the Daily Herald Archive capture behind-the-scenes moments from a mostly missing Doctor Who story called ‘Galaxy 4’ and a nearly complete story called ‘The Web of Fear’.

Since 1981, hundreds if not thousands of films have been returned to the BBC, ITV and other archives. But there is always the possibility of more being discovered. Every year the BFI hold their ‘Missing Believed Wiped’ event, where recently returned or discovered media is played to a sellout audience. Last year’s event screened a Frankie Howerd pilot, long thought lost, some rediscovered UK episodes of Fraggle Rock and early colour footage of the Bee Gees performing on the TV show Once More with Felix.

There are film collectors around the world who have vast collections, some not realising that there are gems hidden among the cans. A study is currently being conducted with ‘Film is Fabulous’ and De Montfort University to catalogue a deceased film collector’s private collection. Already, with less than a third of the collection catalogued, many missing programmes have come to light.

So check your attic, raid grandad’s shed, email overseas television archives. There are more treasures to be found!

Fabulous article. Very interesting, thank you.

As a cinematographer who freelanced for the BBC in New York from 1979 thru 1997, working on 183 documentary assignments including many Top of the Pops with Jonathan King, I similarly developed my USA archive which now includes over 20,000 very scarce or “lost” television broadcasts (1946-1982) surviving only as AUDIO (www.atvaudio.com).