The museum is home to millions of objects and images that trace the history of photography. This post is the first in an alphabetical journey that will explore varied aspects of our world-class collection—starting with A is for… Frederick Scott Archer.

Frederick Scott Archer made what is undoubtedly one of the most important contributions to the progress of photography during the 19th century: the discovery of the wet-collodion process.

Archer’s discovery revolutionised photography by introducing a process which was far superior to any then in existence and which soon superseded all other methods. Yet he was to die just six years later in poverty.

Today, compared to his contemporaries, Talbot and Daguerre, he is little remembered for his pioneering photographic work.

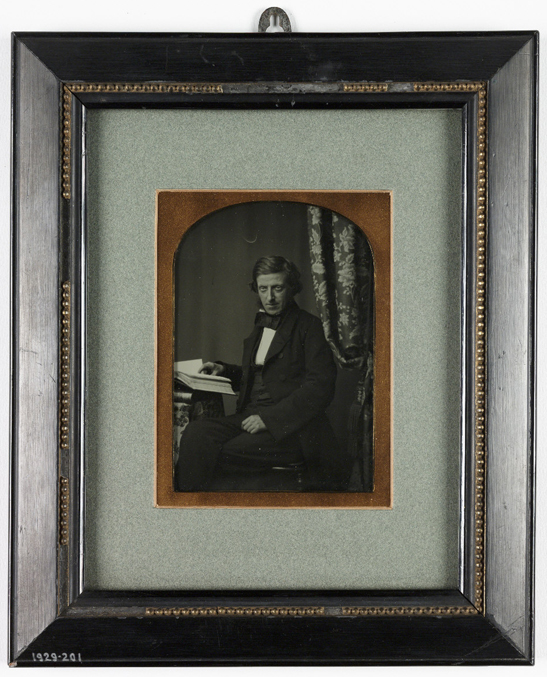

Archer was born in Hertford, Hertfordshire, in 1814. His mother died in 1817 when he was two years old. His father was a prominent local farmer who became the town’s mayor in 1818. As a young boy, Archer was apprenticed to a bullion dealer and silversmith in London. He later turned his attention to portrait sculpture and took up photography in 1847 to assist with his sculpting.

1851: Frederick Scott Archer discovers the wet-collodion process

Archer used Talbot’s calotype process which produced paper negatives but, dissatisfied with the results, he soon began his own experiments to develop a more sensitive and finely detailed process.

For his experiments Archer used collodion—a newly-discovered substance which was used as a medical dressing. A sticky solution of gun cotton in ether, collodion dried quickly to produce a tough, transparent, waterproof film.

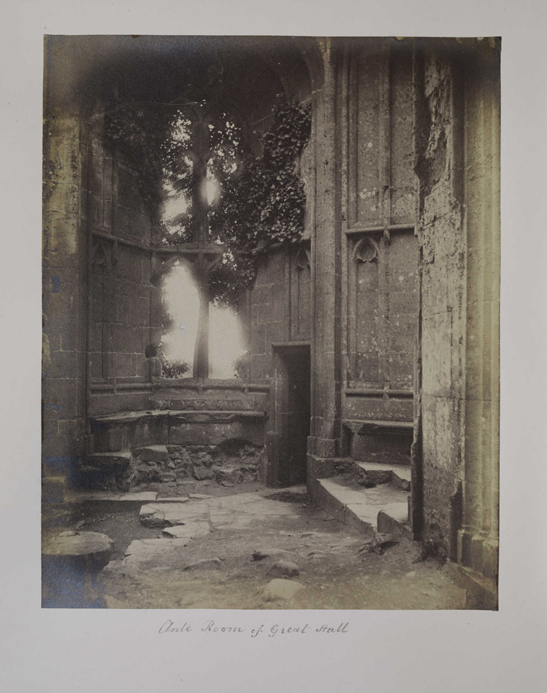

The process he discovered was to coat a glass plate with collodion mixed with potassium iodide and then immerse the plate in a sensitising solution of silver nitrate. Exposed in the camera while still wet, the plate was then developed and fixed immediately. Crisp, detailed negatives were produced by exposures of only a few seconds.

Initially called the Archertype, but commonly known as the wet-collodion process, Archer’s process was to dominate photography for the next thirty years.

In 1851, Archer published his results in the journal The Chemist, where he gave full and detailed instructions on the process. Had Archer been motivated purely by personal gain, he could have patented his invention. His friends certainly encouraged him to do so. As it was, however, he gave his invention freely to the world where it was soon enthusiastically taken up by others.

In 1856, the Liverpool Photographic Journal commented:

Mr Archer’s disinteredness cannot be too highly or substantially complimented… the discovery might have been worth a fortune… In every direction indeed in which we turn, we perceive alike its value and the generosity which bestowed it—free as air, for the public good.

This film, produced by The Getty, illustrates the wet-collodion process step by step.

1853: Archer designs the folding collodion camera

Archer was interested in camera design as well as photographic chemistry. In April 1853, he demonstrated a camera made to his own design at a meeting of the Photographic Society.

Archer’s camera, ‘where the whole process of a negative picture is completed within the box itself’, was also a portable darkroom. At the back of the camera were two black velvet sleeves, through which the photographer could put his hands to manipulate the glass plate—sensitising, developing and fixing it.

An amber window allowed the photographer to see what they were doing. Trays and bottles of chemicals were stored inside the camera. When folded for carrying, the camera was very compact, measuring only about 12in x 12in x 18in.

Folding collodion cameras based on Archer’s design were made and sold by Thomas Ottewill & Co from 1854.

1857: Frederick Scott Archer dies, practically penniless

Others were to benefit from Archer’s work and, indeed, a lucky few were to make their fortunes. Archer himself, however, was not so fortunate. His easy-going, generous nature, combined with poor health, prevented him from aggressively pursuing the financial rewards that were rightly his.

In May 1857 Archer died, practically penniless, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, London. His family were awarded a government pension of £50 per annum ‘in consideration of the scientific discoveries of their father’ and members of the Photographic Society contributed £767 in recognition that he was:

… the true architect of all those princely fortunes which are being acquired by the use of his ideas and inventions.

Sadly, Archer’s wife, Fanny, died a few month’s later, leaving three orphaned children. Of these, only one, Alice, survived to adulthood.

This is an edited version of an article which first appeared in Black & White Photography magazine in December 2008.

Further reading and interesting links

- Frederick Scott Archer: A website devoted to Archer’s life and work

- Catchers of the Light, Dr Stefan Hughes: A new short biography of Archer

- ‘The Collodion Process on Glass’ by Frederick Scott Archer, 1854

- Exhibitions of Frederick Scott Archer’s photographic work 1839–1865

It’s a pity that the Photographic world, apart from George Eastman House, appeared to ignore both the the 150th.anniversary of his publication of the process in The Chemist in 2001 and of his death in 2007.

http://www.samackenna.co.uk/fsa/FSArcher.htm

We could be reminded of Tesla, who invented the induction motor, still in mass use today. He also died broke with all of his papers being taken (stolen) by the government.

Life can be so very unfair with many useless singers and actors making millions, while those true geniuses withered.

Never heard of Archer but it looks like he really was a really amazing inventor.